- Despite common misconceptions that only girls get eating disorders, boys can experience any type of eating disorder.

- Boys with eating disorders may be more likely to be concerned about gaining muscle and being lean rather than losing weight.

- Recovery from an eating disorder is possible thanks to treatment programs, such as Equip, that offer medical care, therapy, nutrition education, and peer and family support.

When her son was 14 years old, Jenny (name changed to protect privacy) noticed his approach to food patterns didn’t feel right. “He had all the common symptoms of anorexia,” Jenny explained.

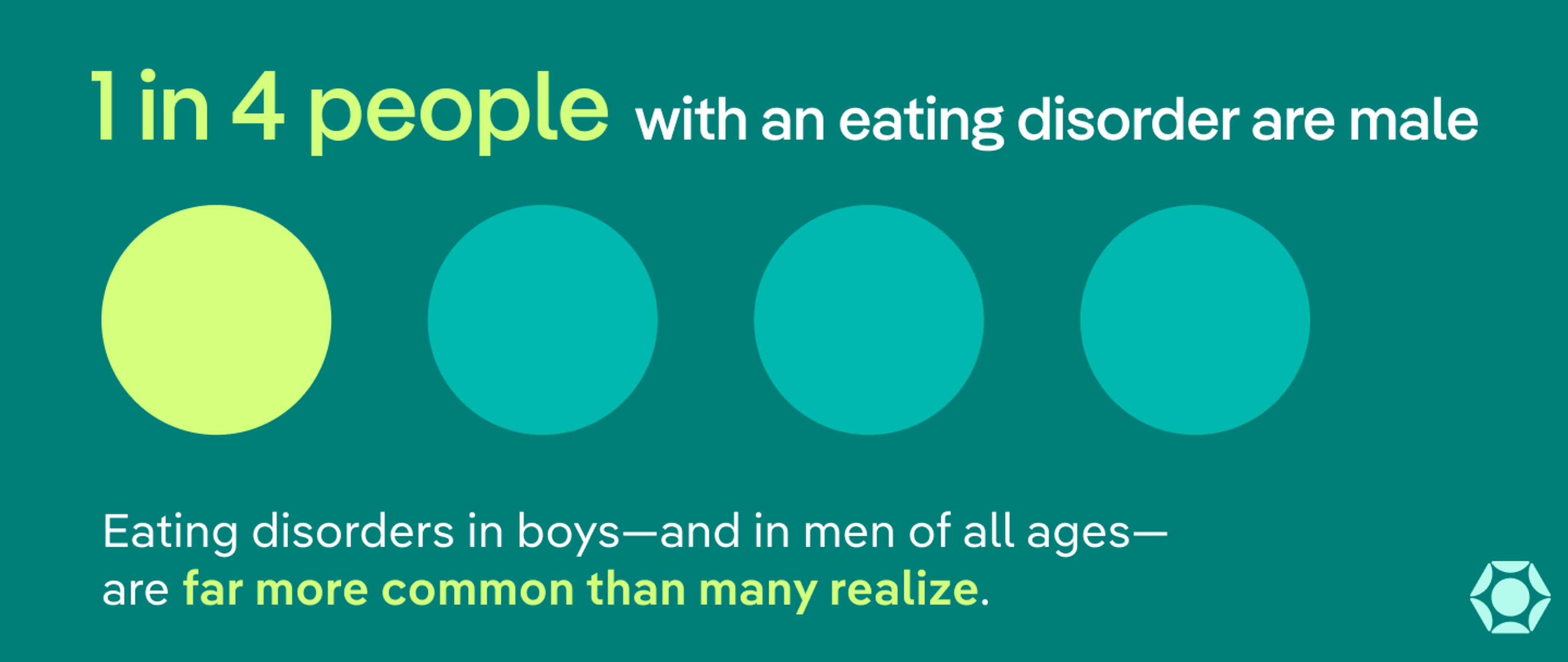

Eating disorders in boys—or boys and men of any age—are not uncommon. Despite the misconception that eating disorders mainly affect girls, research suggests at least 1 in 4 people with an eating disorder are male. But the number may be higher due to how many boys go undiagnosed. We also know that rates of eating disorders in males are increasing at a faster rate than in females. However, eating disorders in males and females can look different, which is one reason they are typically underrecognized.

On top of his food patterns, “he's a high performing athlete,” Jenny said of her son. “He was just exercising like crazy.” By the time her son turned 15, Jenny decided it was time for an intervention.

Jenny turned to Equip for her son’s treatment. The journey to get her son back to a healthy weight range took a lot of effort for the whole family. But her son was willing to do the work. “He did everything that we asked him to do in terms of refeeding,” Jenny said.

Now, Jenny’s son on his way to recovery. Jenny said he doesn’t like to talk about his eating disorder, but he’s made a lot of progress.

Here’s an at-a-glance snapshot of how eating disorders in boys look different from eating disorders in girls.

| Aspect | Boys | Girls |

| Body-image focus | Muscularity, leanness, low body fat, size/definition | Thinness, weight loss |

| Common behaviors | Compulsive exercise, protein fixation, supplements to bulk up, “clean eating” | Restriction, binge-purge behaviors |

| What parents notice | Increased workouts, rigid food rules, emphasis on muscles or definition | Visible weight changes, food avoidance, dieting |

| Hidden signs | Muscle dysmorphia, performance-enhancing aids, excessive exercise, “clean” eating, protein fixation | Body checking, calorie counting rituals, dramatic food rule changes |

In this article, we’ll break down what eating disorders look like in boys, why they’re often missed, what signs to look out for, how to talk to your child if you’re concerned, and what to expect from treatment.

One thing to note. We’ll use terminology like “boys” and “men” throughout this article. Just remember that gender isn’t binary, and people of any gender can and do develop eating disorders. We’re opting to use “boys” and “men” to support an overlooked group of people with eating disorders.

What types of eating disorders affect boys?

Boys can experience any type of eating disorder, even those typically associated with girls. The most common eating disorders in boys include:

- Anorexia: Restricting energy intake along with an intense fear of gaining weight.

- Bulimia: Binge eating and then compensating using purging behaviors such as vomiting or excessive exercise.

- Binge eating disorder: Recurring episodes of binge eating accompanied by feeling out of control and ashamed of bingeing behaviors.

- ARFID (avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder) : Avoiding food due to a lack of interest or low appetite, sensory sensitivities, or fear of something bad happening while eating.

- Muscle dysmorphia: Also called bigorexia, being preoccupied with a perceived lack of muscles that leads to distress and attempts to change body size and shape. Muscle dysmorphia isn’t an official eating disorder diagnosis, but it can be a symptom of eating disorders or lead to developing one.

Keep in mind that boys may appear to be a “healthy” size, but that doesn’t necessarily mean everything is fine. “Looks are not a great indicator of health,” Levine says.

Let’s take a closer look at each of these.

Anorexia in boys

Anorexia is an eating disorder that causes food restriction along with an intense fear of weight gain. Boys with anorexia, however, may be more preoccupied with building muscle, having a low percentage of body fat, and developing certain physical features rather than losing weight.

“What I'll often hear in teenage boys is they desire to have a six pack or to have a really chiseled jawline or really pronounced features,” says Jonathan Levine, LCSW, therapy lead for Equip. In fact, in one study, up to 60% of boys said they changed their diet to build bigger muscles.

Below are other signs to look for that could point to male anorexia.

Physical signs of anorexia in boys include:

- Weight loss or slower growth

- Muscle weakness

- Delayed puberty

- Digestive issues like constipation

- Low blood pressure, which can lead to dizziness and feeling faint

- Fatigue

- Low heart rate

- Getting cold easily

- Brittle nails and hair

- Fine hair on the face and body (lanugo hair)

Emotional signs of anorexia in boys include:

- Intense fear of gaining weight

- Distorted body image

- Denial of the seriousness of their symptoms

- Perfectionism

Behavioral signs of male anorexia can include:

- Restricting food intake

- Cutting out entire food groups

- Compulsive exercise or excessive weight lifting

- Obsessing over “healthy” foods or certain food groups

- Having strict food rules

- Withdrawal from others

- Excessive body checking or weighing themselves

Bulimia in boys

Bulimia—episodes of binge eating followed by behaviors to compensate for the binge, known as purging—often looks similar in boys and girls, Levine says. Purging behaviors may include vomiting, overexercising, and laxative use. But again, boys are typically more focused on building muscle rather than losing weight.

Physical symptoms of bulimia in boys include:

- Sore and inflamed throat from vomiting

- Enlarged salivary glands that cause puffy cheeks or jaw swelling

- Scars or scrapes on the knuckles or hands from vomiting

- Loss of enamel on teeth

- Acid reflux and other digestive issues

- Dehydration

- Electrolyte imbalances

Emotional signs of bulimia in boys include:

- Excessive focus on body weight, shape, or size

- Fear of weight gain or preoccupation with muscularity

- Guilt, shame, or disgust about eating habits

- Depression

- Anxiety

Behavioral symptoms of bulimia in boys include:

- Binge eating followed by vomiting, excessive exercise, or restricting calories

- Going to the bathroom after meals

- Exercising more than usual

- Fasting

- Taking laxatives, diet pills, or diuretics

- Using supplements or performance-enhancing drugs (like steroids)

- Eating in secret

Hiding food wrappers

Binge eating disorder in boys

Binge eating disorder occurs when people eat a large amount of food in a short amount of time. They may feel out of control when bingeing and then experience distress and feelings of shame or guilt.

Physical signs of binge eating disorder in boys include:

- Weight changes

- Sleep issues

- Digestive issues, including bloating, acid reflux, and diarrhea

- Fatigue

Emotional signs of binge eating disorder in boys include:

- Feeling guilt, shame, or distress after bingeing

- Having a negative body image

- Low self-esteem

- Difficult emotions that trigger binge episodes

Behavioral signs of binge eating disorder in boys include:

- Eating a large amount of food quickly in a short period of time

- Eating even when already full or not hungry

- Eating to the point of discomfort

- Hiding evidence of binge eating

- Avoiding eating with others

- Hoarding or hiding food

- Withdrawing from friends and family

- Dieting

Binge eating behaviors in boys can also hide in plain sight, because “it is normalized for men to eat more food,” Levine says.

“When a boy is eating a large amount of food, you'll often hear adults, coaches, teachers be like, ‘Oh, you were so hungry,’ or ‘You must be growing,’” Levine adds. “[Adults aren’t] really diving deeper into the possibility that maybe there is an eating disorder going on.”

ARFID in boys

ARFID involves restricting food intake due to sensory sensitivities, being uninterested in food, having a lack of appetite, or fearing negative consequences from eating. It’s not driven by body image concerns like other eating disorders. But people with ARFID may have body image concerns just like anyone else.

ARFID can be caused by childhood feeding issues and sensitivities. It also commonly occurs alongside other mental health issues and neurodivergences such as:

- Major depression

- Generalized anxiety disorder

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Autism

- Sensory processing disorder

- Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

Boys are just as likely as girls or even more likely to have ARFID.

Physical symptoms of ARFID in boys include:

- Weight loss or not growing as expected

- Malnutrition

- Fatigue

- Digestive issues such as stomach pain or constipation

- Pale complexion, brittle hair, or weakened nails

Emotional signs of ARFID in boys include:

- Feeling anxious about eating or being around food

- Fear of choking, throwing up, or experiencing stomach discomfort

- Fear of trying new foods

- Irritability

- Mood changes

- Difficulty concentrating

Behavioral signs of ARFID in boys include:

- Restricting types of food eaten

- Refusing to try new foods

- Avoiding certain foods based on their smell, texture, or what they look like

- Narrowing their range of preferred foods

- Forgetting to eat

- Refusing to eat entire food groups

- Severe pickiness that makes shared meals or social events difficult

- Choosing supplements or meal replacement shakes instead of foods

Muscle dysmorphia in boys

Muscle dysmorphia, which is a form of body dysmorphia, is most common among males. Muscle dysmorphia occurs when someone is preoccupied building muscle and reducing body fat. It causes significant distress and leads boys to engage in behaviors to fix their perceived “flaws.” It’s also referred to as bigorexia, though this isn’t an official eating disorder diagnosis.

Physical signs of bigorexia in boys include:

- Changes in weight or body shape

- Extra muscle definition

Emotional signs of bigorexia in boys include:

- Obsession with looks

- Intense dissatisfaction with body appearance

- Depression

- Comparing bodies with others

Behavioral signs of bigorexia in boys include:

- Compulsive exercise and excessive weight lifting

- Rearranging activities to exercise instead

- An intense focus on diet and a desire to “burn off” meals

- Dieting and strict food rules or focus on “clean” eating

- Fixation on protein intake

- Using “bulking and cutting” cycles to build muscle

- Overusing or feeling compelled to use supplements

- Using steroids

- Frequent body checking

- Avoiding mirrors

- Asking for reassurance about appearance

- Hiding parts of the body in their clothing

- Rigid rules around food or body

What are warning signs of eating disorders in boys?

There are some common symptoms of eating disorders to watch for in boys regardless of the type of eating disorder someone may have. Keep in mind that you can’t tell someone has an eating disorder by looking at them. Many eating disorder behaviors also happen in secret.

If you’re unsure about your son’s symptoms, Equip’s free eating disorder screener will help you determine whether your son’s behaviors indicate an eating disorder.

Physical signs

Look for these common physical changes that could mean someone has an eating disorder:

- Weight loss

- Lack of weight gain, especially in developing children and teens

- Fatigue

- Dizziness

- Weakness

- Getting cold easily

- Digestive issues like nausea, constipation, or acid reflux

- Brittle nails and hair

“Weight loss in a growing child should always be a situation to explore,” says Lauren Muhlheim, Psy.D., FAED, CEDS-S, certified eating disorder specialist at Eating Disorder Therapy LA. “Because growing children are supposed to be regularly gaining weight, sometimes lack of weight gain is an even earlier sign.”

Behavioral signs

Watch for behavior changes around food and exercise. Behavioral signs of eating disorder in boys include:

- Compulsive exercise

- Using supplements and other performance-enhancing substances

- Eating alone or avoiding eating with others

- Body checking

- Restricting food intake

- Cutting out entire food groups from their diet

- Having strict food rules

- Hoarding or hiding food

- Withdrawal from activities that involve food

Emotional signs

Not all signs of an eating disorder are physical or easy to observe. But these emotional signs of an eating disorder in males are just as important to pay attention to:

- Fixation on muscularity and low body fat

- Fear of weight gain

- Shame or guilt after eating

- Anxiety

- Irritability

- Depression

- Perfectionism

- Distorted body image

- Difficulty acknowledging or openly discussing symptoms

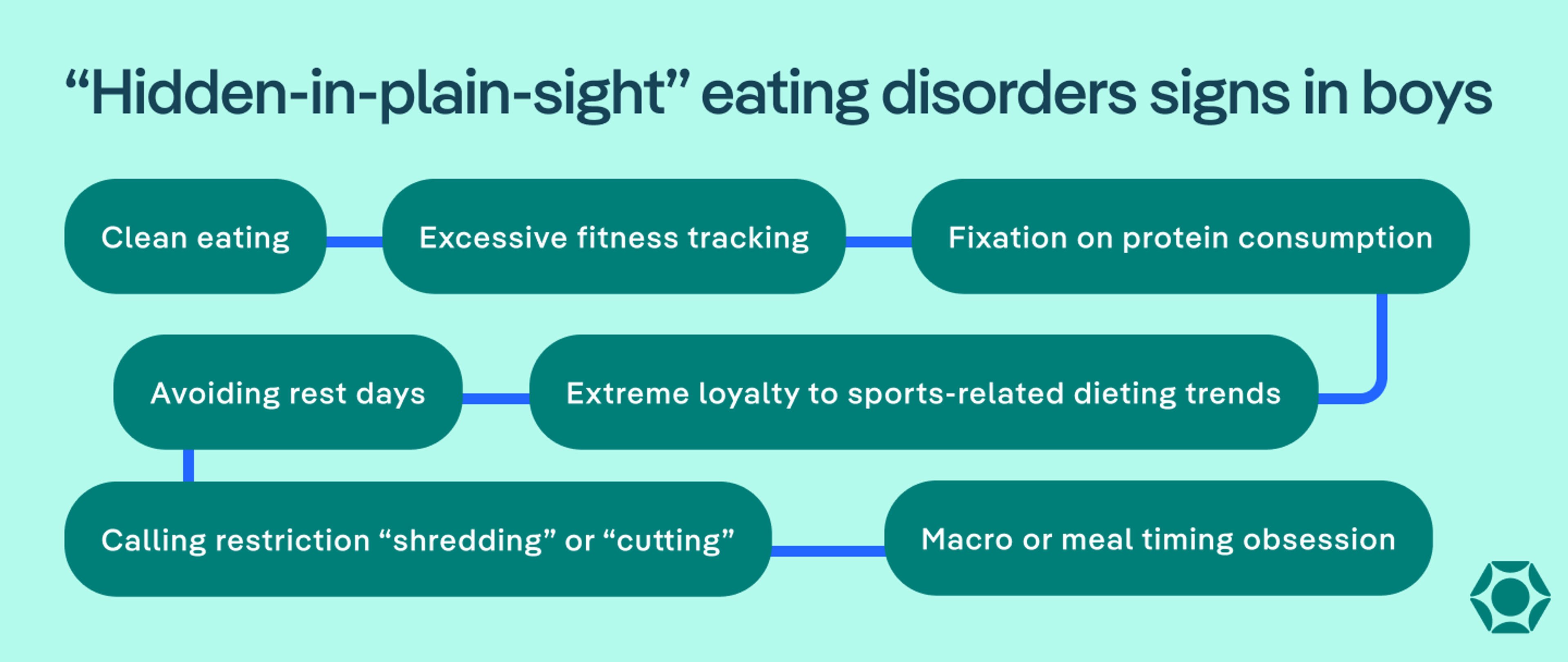

“Hidden-in-plain-sight” signs

Boys with eating disorders may experience subtle symptoms that hide in plain sight. These are often associated with diet culture and behaviors sometimes considered “normal” or “healthy.” But “just because society is normalizing our behavior doesn't mean it's normal,” Levine says.

Watch for behaviors that might be praised as “healthy” or being “disciplined,” including:

- Clean eating

- Fixation on protein consumption

- Excessive fitness tracking

- Cycles of bulking (eating a lot) and then cutting (restricting food)

- Calling restriction “shredding” or “cutting”

- Avoiding rest days

- Macro or meal timing obsession

- Extreme loyalty to sports-related dieting trends

Eating disorders in boys can also hide in athletics, where getting muscular, focusing on certain food groups, or exercise are praised. Depending on an athlete’s sport, there may also be pressure to maintain a specific weight or a certain look such as leanness. Eating disorders in male athletes are more common in weight-sensitive sports like wrestling, gymnastics, diving, and running.

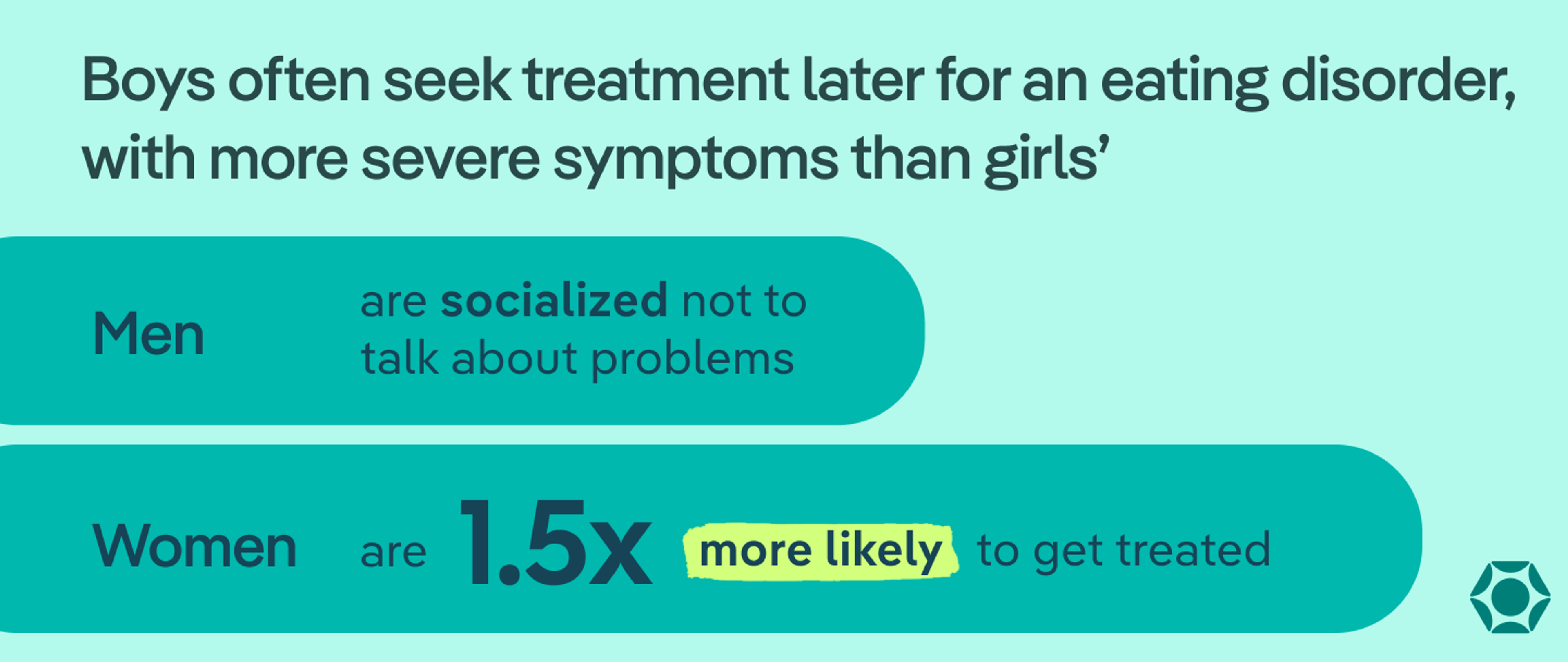

Why are eating disorders in boys often missed?

“Quite simply, eating disorders in boys are often missed because of the stereotyped image of who gets eating disorders,” Muhlheim says. Eating disorders are typically associated with girls.

“Consequently, parents and health professionals may be less likely to recognize an eating disorder,” Muhlheim adds. “This leads to later diagnosis of eating disorders in boys.”

Men may not recognize their eating disorder is a problem because of the stigma that these conditions only affect women. Their disordered patterns may also not fit the stereotype of what an eating disorder looks like, further delaying diagnosis and treatment.

Boys with eating disorders will typically focus on building muscle and reducing body fat to increase muscle definition. They want to get bigger with more muscle. Girls with eating disorders, on the other hand, focus on getting smaller and losing weight.

Boys and men also may learn to hide their feelings or minimize their symptoms due to male gender norms. “We're not supposed to talk about our feelings. We're not supposed to dive deeper. It's not safe to share and sharing is vulnerable. Vulnerable is weakness,” Levine says. “Because boys and men are socialized not to talk about the problems, [eating disorders are] often not diagnosed until later.”

By the time boys seek treatment, their symptoms are usually more severe than when girls first seek treatment. We also know women are 1.5 times more likely to get treated for an eating disorder compared to men.

What causes eating disorders in boys?

There isn’t a single cause of eating disorders, “but they are believed to be caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors,” Muhlheim says.

Common causes of eating disorders in boys include the following.

Genetic predisposition

Eating disorders have a genetic risk, meaning if someone else in their family has an eating disorder, someone may be more likely to develop one too.

Personality traits

Certain personality traits are associated with developing an eating disorder, including:

- Perfectionism

- Impulsivity

- Tendency toward compulsive behaviors

- Wanting to avoid stress or discomfort

- Anxiety

Having other mental health conditions

Boys with other mental health conditions like depression, generalized anxiety disorder, OCD, or social anxiety disorder have a higher risk of also having an eating disorder. About 70% of people with an eating disorder have at least one other mental health condition.

For eating disorders like ARFID, boys with neurodivergence have a higher risk of also having an eating disorder. ARFID often overlaps with autism and ADHD.

Trauma or high stress

Experiencing trauma or high stress, especially in childhood, can trigger an eating disorder. Traumatic events include things such as physical or sexual abuse, a major loss, parental divorce, or being in an accident.

Cultural and media pressures around muscularity

Boys are exposed to cultural and media images that show muscular men as the ideal body. Think superhero movies and fitness influencers with six-packs, big muscles, and unrealistic body standards. Comparing against these unrealistic ideals can lead to body dissatisfaction and disordered eating patterns.

Social media

“Social media can impact whether they're looking at other people's bodies, like gym goers, fitness influencers, actors, or just hearing people talk about what makes a man a man,” Levine says. These comparisons can contribute to body dissatisfaction and eating disorder patterns.

Pro-eating disorder content on social media is also a problem, Levine says. “We're seeing a rise in pro-eating disorder content, pro-anorexia content, and people who look truly, deathly thin being celebrated for their beauty,” Levine says.

Peer comparisons

Just as boys may compare their bodies with things they see in the media or on social media, they may also compare with their peers. These comparisons can lead to body dissatisfaction and eating disorder behaviors.

How do sports and fitness culture contribute to risk?

“We know that athletes are at a very high risk of developing an eating disorder,” Levine says. Young athletes are up to three times more likely to develop an eating disorder compared to their peers who don’t play sports.

Many sports, especially weight-sensitive sports, put pressure on boys to look a certain way or stay a specific size. In wrestling for example, athletes need to maintain a certain weight, while in running the emphasis is on leanness.

Boys in sports may feel pressured to work extra hard to meet these weight and shape standards. They may also experience pressure from their coaches or peers. Levine says the intense focus on body image and “really scrutinizing your body and finding weak points to develop” can trigger an eating disorder.

Even boys who don’t play a formal sport but just like to work out can have an increased risk of developing an eating disorder. This is especially true if they spend time at a gym with rigid ideas about fitness like restrictive eating and excessive exercise. These toxic gym culture ideas can contribute to eating disorder patterns or trigger an eating disorder.

What are the health risks for boys with eating disorders?

Eating disorders can take a serious toll on boys’ physical and emotional health, especially during the years when their bodies and brains are still developing. Below are health concerns to watch for if your son or another loved one is struggling with an eating disorder.

Hormonal changes

Eating disorders can lower testosterone levels and delay normal puberty, affecting development, mood, and energy. Testosterone is also important for developing muscle, reducing injury risk, and building endurance.

Growth suppression

Inadequate nutrition may slow or halt height and weight gain during critical growth periods. During the developmental years, a child should regularly be gaining weight. But an eating disorder and restricting calories can slow growth and normal weight gain because the body doesn’t have enough energy.

Bone density loss

Disordered eating can make bones weaker, which can lead to stress fractures and increase the risk of osteoporosis. Over time, osteoporosis makes bones thinner and more fragile, so they’re more likely to break.

Gastrointestinal distress

Restriction, bingeing, or purging can lead to stomach pain, constipation, bloating, acid reflux, diarrhea, and other digestive issues.

Heart risks in severe restriction

Extremely low calorie intake can slow the heart rate and cause heart rhythm problems. When the heart rate gets too low, boys may experience fatigue, dizziness, and they could faint. In severe cases, these heart issues can lead to heart attacks.

Injuries due to overtraining

Excessive exercise can lead to muscle strains, stress fractures, and chronic injuries.

Mental health risks

Boys may face depression, anxiety, and chronic feelings of guilt and shame as their eating disorder progresses. Those with eating disorders also have a higher risk of suicide. Call the national suicide hotline at 988 if you’re concerned your child may be at risk for suicide.

Effects of supplement or steroid misuse

Overuse of supplements or anabolic steroids can damage many organs in the body, including the liver, kidneys, and heart.

Serious effects of anabolic steroids in particular include:

- High blood pressure

- Blood clots

- Artery damage

- Low sperm count

- Baldness

- Infections

- Agression

- Severe acne

Long-term health risks if untreated

Without treatment, boys with eating disorders may experience lasting impacts on physical development, fertility, bone health, and overall well-being.

How can you start a conversation about eating or body concerns?

The best way to start a conversation is to speak up as soon as you suspect something is wrong. From there, “if your child is showing signs of eating or body concerns, it’s always a good idea to mention what you notice and ask them about it,” Muhlheim says.

Start the conversation with support but be straightforward and present just the facts. For example:

- “I’ve noticed you’re lifting weights a lot more than you used to. Can you tell me about this?”

- “You used to love ice cream, and now you’ve cut it out completely. Can you talk to me about why?”

- “You’re really exercising a lot right now, but I noticed you’re not eating as much as you used to. Do you think you’re fueling enough for your level of activity?”

You can also ask about what media they are watching to get a better idea of their body ideals.

Keep in mind that someone may not be ready to admit they have an issue, or they may not recognize that their food and fitness behaviors are harmful.

“If they deny it, it may not mean that they don’t have an issue,” Muhlheim says. “A lack of awareness is often a symptom of an eating disorder in children and teens. Keep watching and trust your judgement.”

What are treatment options for boys with eating disorders?

The sooner you’re able to get someone into eating disorder treatment, the better. “Early intervention matters because it reduces the potential for medical complications, delayed puberty, and stunted growth. It also leads to better outcomes,” Muhlheim says.

The good news is there are several evidence-based treatment options that get boys with eating disorders the help they need. In most cases, treatment will require a team of professionals who can support your son’s recovery journey. At Equip, for example, boys with eating disorders work with a medical provider, therapist, registered dietician, family mentor, and peer mentor.

Here’s what to look for in an eating disorder treatment program and other ways to find support for your son and your family.

Family-based treatment (FBT)

The gold standard for eating disorders “for anyone 18 and under is called family-based treatment, or FBT,” Levine says. “That's what I would recommend for anyone who has family support.”

FBT puts parents and loved ones in the front seat of the eating disorder recovery process. During the first phase of treatment, the family is in full control. You make all the food and exercise choices for your child in order to get their physical health back on track. This means making decisions about, preparing, and supervising everything your child eats for a period of time until they start recovering physically.

As treatment progresses, you’ll gradually return food choices and eating back to your child until they’re in full developmentally appropriate control again. You’ll complete the whole process with the support of a specialized therapist and the rest of your son’s treatment team.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

Cognitive behavioral therapy—enhanced (CBT-E), also referred to as enhanced CBT, is another effective tool for treating eating disorders.

During CBT-E, a therapist may address topics such as restoring a healthy weight, body image, restriction, or eating and moods. Over time, the goal is to help boys get a handle on the factors that cause their eating disorder so they can fight against it.

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT)

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is a type of therapy that focuses on four major sets of skills: mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotion regulation, and interpersonal skills. The goal is to help boys shift away from problematic coping mechanisms—like disordered eating and compulsive exercise—to more adaptive skills to manage difficult emotions and situations.

Medical care

Treatment for eating disorders includes medical care to monitor a child’s physical health. Your medical provider will help develop a plan for safe recovery, track weight and vital signs, monitor any health issues, and manage prescriptions if needed.

Tailoring treatment for boys

Treatment should include elements that highlight the unique aspects of having an eating disorder as a male. “It's really important to look at gender norms and what is expected of anyone,” Levine says.

This could include examining the role models boys look up to on social media, discussing how stigma affects their feelings about their disorder, and talking about what society considers “normal” for men versus the reality.

Family support

“Family support is really everything,” Levine says. “Eating disorders really thrive in isolation and secrecy, [so] getting other people in the mix … can be really critical.”

Support can come directly from immediate family, but don’t rule out other support people. This could include extended family, other trusted adults, and friends who understand what’s going on. Levine says even checking in with boys via FaceTime, Zoom, or text can go a long way.

Support groups

Eating disorder support groups can help reduce the stigma of having an eating disorder and let boys know they’re not alone. It offers them the opportunity to talk with other boys and young men going through the same thing, which is important.

Support groups are an important component of treatment for caregivers too, because it’s not easy having a child in recovery. That’s why treatment providers like Equip offer support groups specifically for boys and men and for caregivers of boys.

Virtual eating disorder care

Virtual treatment can be especially helpful for families with a medically stable son who has an eating disorder. It’s just as effective as in-person care, while offering flexibility and convenience. Virtual care—like Equip’s virtual eating disorder program—makes it easier for families to balance work and other responsibilities alongside treatment.

When and how to seek help

“If a parent or a loved one notices a shift in someone’s eating habits, I would always recommend they get screened for an eating disorder really soon,” Levine says.

Specific signs that mean it’s time to talk with a professional include:

- Hyperfocus on health

- Desire to lose weight

- Hyperfocus on getting “jacked” and building muscles

- Shifts in how much they’re eating, such as suddenly skipping breakfast or they start fasting

- Cutting out foods they used to love entirely

Keep an eye out for things that are often considered “healthy” in our society, such as cutting out all sugar. While these shifts in food intake are often celebrated, they can point to an eating disorder in boys. “Any drastic shift with the goal of changing your body should be really scrutinized,” Levine says.

You can also take Equip’s free eating disorder screener if you’re concerned about yourself, your son or another loved one. It can help you determine potential risk for an eating disorder and whether it’s time to talk with a professional.

And don’t be afraid to reach out to a professional even if you’re not sure. Seeking help early is protective. “Early intervention is the most effective thing for long-term recovery,” Levine says.

Document any changes you notice in behavior around eating and exercise. Even if they seem like small shifts, it doesn’t hurt to make note of them. This way when it’s time to speak with a professional, you’ll be able to lay out all the signs you’ve noticed.

Who to contact first

If you’re worried, reach out to your primary care provider (PCP, which for pediatric patients would be their pediatrician) first, Levine says. That’s usually your first point of contact because your PCP can refer you to other providers. You can also reach out to a mental health professional like a therapist or psychiatrist as your first point of contact.

However, you want to make sure your child is seen by a qualified healthcare professional who understands eating disorders and what they look like in boys. Otherwise, your doctor may dismiss your son’s disordered behaviors as “healthy,” or as “nothing to worry about,” which can make the problem worse.

To assess whether your PCP, pediatrician, or any healthcare professional is qualified, Levine says to ask them:

- Have you heard of the health at every size movement?

- Are you familiar with eating disorders?

Keep asking providers until you find one who has the right experience. Most healthcare professionals will be honest about their expertise. And if your provider dismisses your concerns, trust your gut and look for another provider who will take you seriously. “One more extra appointment may be a hassle, but it's really worth getting ahead of this,” Levine says.

What to do if your child resists help

You’re not alone if your son resists treatment. “That's a feature of the disease, not a bug,” Levine says. The best thing you can do is ask for help. “Finding a way to get additional support from professionals, from specialized eating disorder providers, from support groups is really critical,” Levine says. “No one can do this alone.”

Equip, for example, offers eating disorder support groups specifically for boys, men, and caregivers. Specialized eating disorder providers will also be able to give you guidance on how to manage your child’s resistance.

The bottom line

Despite the misconception that only girls get eating disorders, at least 25% of people with eating disorders are male. However, eating disorders often look different in boys compared to girls. Boys with eating disorders typically focus on leanness and gaining muscle compared to losing weight. Their eating disorder may also hide behind diet culture trends like a fixation on protein, restricting certain food groups, or “bulking and cutting.”

If your child or another loved one shows signs of an eating disorder, getting them help as soon as possible will help put them on the road to recovery faster. With a knowledgeable medical and mental health treatment team and evidence-based therapies like FBT and CBT-E, it is possible for anyone to enter and sustain lasting eating disorder recovery. And best of all, it’s always worth it.

Remember, you don’t need to do it alone—ask for help when you need it.

Alizadeh Pahlavani, Hamed, and Ali Veisi. “Possible consequences of the abuse of anabolic steroids on different organs of athletes.” Archives of Physiology and Biochemistry, vol. 131, no. 3, 3 Feb. 2025, pp. 393–409, https://doi.org/10.1080/13813455.2025.2459283.

Barakat, Sarah, et al. “Risk factors for eating disorders: Findings from a rapid review.” Journal of Eating Disorders, vol. 11, no. 1, 17 Jan. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-022-00717-4.

Davani-Davari, Dorna, et al. “The potential effects of anabolic-androgenic steroids and growth hormone as commonly used sport supplements on the kidney: A systematic review.” BMC Nephrology, vol. 20, no. 1, 31 May 2019, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-019-1384-0.

DeBoer, Lindsey B., and Jasper A. Smits. “Anxiety and disordered eating.” Cognitive Therapy and Research, vol. 37, no. 5, 4 July 2013, pp. 887–889, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-013-9565-9.

Dipla, Konstantina, et al. “Relative energy deficiency in sports (red-S): Elucidation of endocrine changes affecting the health of males and females.” Hormones, vol. 20, no. 1, 17 June 2020, pp. 35–47, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42000-020-00214-w.

Downey, Amanda E., et al. “Linear growth in young people with restrictive eating disorders: ‘inching’ toward consensus.” Frontiers in Psychiatry, vol. 14, 3 Mar. 2023, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1094222.

“Eating Disorders: What You Need to Know.” National Institute of Mental Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2024, www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/eating-disorders.

Eisenberg, Marla E., et al. “Muscle-enhancing behaviors among adolescent girls and boys.” Pediatrics, vol. 130, no. 6, 1 Dec. 2012, pp. 1019–1026, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-0095.

Farstad, Sarah M., et al. “Eating disorders and personality, 2004–2016: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Clinical Psychology Review, vol. 46, June 2016, pp. 91–105, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.04.005.

Ganson, Kyle T., et al. “‘bulking and cutting’ among a national sample of Canadian adolescents and young adults.” Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, vol. 27, no. 8, 9 Sept. 2022, pp. 3759–3765, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-022-01470-y.

Glazer, Kimberly B., et al. “The course of weight/shape concerns and disordered eating symptoms among adolescent and young adult males.” Journal of Adolescent Health, vol. 69, no. 4, Oct. 2021, pp. 615–621, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.03.036.

Gorrell, Sasha, and Stuart B. Murray. “Eating disorders in males.” Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, vol. 28, no. 4, Oct. 2019, pp. 641–651, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2019.05.012.

Kaşak, Meryem, et al. “Selective eating and sensory sensitivity in children with ADHD: A comparative study of arfid symptom profiles.” International Journal of Eating Disorders, vol. 58, no. 10, 28 July 2025, pp. 1991–2002, https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.24512.

Keski-Rahkonen, Anna, and Linda Mustelin. “Epidemiology of Eating Disorders in Europe.” Current Opinion in Psychiatry, vol. 29, no. 6, Nov. 2016, pp. 340–345, https://doi.org/10.1097/yco.0000000000000278.

Koreshe, Eyza, et al. “Prevention and early intervention in eating disorders: Findings from a rapid review.” Journal of Eating Disorders, vol. 11, no. 1, 10 Mar. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00758-3.

Le Grange, Daniel, et al. “Enhanced cognitive-behavior therapy and family-based treatment for adolescents with an eating disorder: A non-randomized effectiveness trial.” Psychological Medicine, vol. 52, no. 13, 3 Dec. 2020, pp. 2520–2530, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291720004407.

Magee, Meghan K., et al. “Body composition, energy availability, risk of eating disorder, and sport nutrition knowledge in young athletes.” Nutrients, vol. 15, no. 6, 21 Mar. 2023, p. 1502, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15061502.

Mancine, Ryley P., et al. “Prevalence of disordered eating in athletes categorized by emphasis on leanness and activity type – A systematic review.” Journal of Eating Disorders, vol. 8, no. 1, 29 Sept. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-020-00323-2.

Mitchison, Deborah, et al. “Prevalence of muscle dysmorphia in adolescents: Findings from the EveryBody study.” Psychological Medicine, vol. 52, no. 14, 16 Mar. 2021, pp. 3142–3149, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291720005206.

National Eating Disorders Association. “Eating Disorders and Trauma.” National Eating Disorders Association, 23 Sept. 2025, www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/eating-disorders-and-trauma/.

National Institutes of Health. “Anabolic Steroids and Other Appearance and Performance Enhancing Drugs (Apeds).” National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 11 July 2024, nida.nih.gov/research-topics/anabolic-steroids#side_effects.

New York State Department of Health. “Eating Disorders and Your Bones: Get the Facts.” New York State Department of Health, www.health.ny.gov/publications/2049/index.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2025.

Patel, Riti, et al. “Cardiovascular impact of eating disorders in adults: A single center experience and literature review.” Heart Views, vol. 16, no. 3, 2015, p. 88, https://doi.org/10.4103/1995-705x.164463.

Ramirez, Zerimar, and Sasidhar Gunturu. “Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder.” StatPearls, 1 May 2024.

Räisänen, Ulla, and Kate Hunt. “The role of gendered constructions of eating disorders in delayed help-seeking in men: A qualitative interview study.” BMJ Open, vol. 4, no. 4, Apr. 2014, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004342.

Sader, Michelle, et al. “Prevalence and characterization of avoidant restrictive food intake disorder in a pediatric population.” JAACAP Open, vol. 1, no. 2, Sept. 2023, pp. 116–127, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaacop.2023.05.001.

Smith, April R, et al. “Eating disorders and suicidality: What we know, what we don’t know, and suggestions for future research.” Current Opinion in Psychology, vol. 22, Aug. 2018, pp. 63–67, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.08.023.

Sonneville, K. R., and S. K. Lipson. “Disparities in eating disorder diagnosis and treatment according to weight status, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic background, and sex among college students.” International Journal of Eating Disorders, vol. 51, no. 6, 2 Mar. 2018, pp. 518–526, https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22846.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. “Table 23, DSM-IV to DSM-5 Body Dysmorphic Disorder Comparison - DSM-5 Changes - NCBI Bookshelf.” DSM-5 Changes: Implications for Child Serious Emotional Disturbance [Internet]., U.S. National Library of Medicine, June 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books.

Velimirović, Mina, et al. “Anxiety, obsessive‐compulsive, and depressive symptom presentation and change throughout routine eating disorder treatment.” European Eating Disorders Review, vol. 33, no. 3, 28 Nov. 2024, pp. 490–502, https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.3160.