- Orthorexia is a fixation on eating “pure” or “clean” foods that can cause significant anxiety, nutritional harm, and social isolation—even when it looks “healthy” from the outside.

- Although orthorexia nervosa is not currently a formal DSM diagnosis, the distress and health risks are real and often overlap with the symptoms of diagnosable mental health conditions, like eating disorders, anxiety, and OCD.

- Diet culture, wellness trends, and social media can make orthorexia hard to recognize and even harder to question, since rigid food rules are often praised.

- Early, compassionate support matters. With the right care, orthorexia recovery is possible, and you can rebuild a more peaceful, flexible relationship with food.

For a long time, Equip Peer Mentor Rachel Myers struggled with what she calls “health anxiety.” The fear of getting sick or developing a chronic illness consumed her, sending her down a rabbit hole of strategies meant to protect her body. That search eventually led her to veganism, which became the starting point of something more consuming—an obsessive pursuit of “healthy” eating that quietly took over her life.

Experiences like Myers’ are more common than many people realize, especially in a culture that praises discipline, purity, and self-control around food. What often begins as an attempt to feel better or safer can gradually turn rigid and anxiety-driven, making meals stressful, social eating difficult, and any deviation from food rules deeply distressing.

This pattern has a name. Orthorexia is an unhealthy fixation on eating foods perceived as healthy, clean, or pure. While caring about nutrition is not a problem in itself, orthorexia crosses into dangerous territory when food rules become inflexible, compulsive, and disruptive to daily life and well-being.

Part of what makes orthorexia so confusing is that orthorexia nervosa is not currently a formal diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), despite the very real physical, emotional, and social consequences it can have. That gray area leaves many people wondering whether their distress “counts” as an eating disorder, or whether they’re simply being disciplined or health-conscious.

But the lack of a diagnostic label doesn’t make the suffering any less real. Orthorexia can seriously affect physical health, mental health, relationships, and quality of life, especially in a culture that praises clean eating, self-control, and wellness at all costs. It can also be a slippery slope to a diagnosable eating disorder.

Below, we’ll unpack what orthorexia is, how to recognize it, why cultural pressures make it so hard to spot, and what compassionate, effective treatment and recovery can look like.

What is orthorexia?

“When we talk about orthorexia, we’re referring to the state of being rigidly obsessed with 'clean' eating patterns in a way that obstructs normal functioning and daily life,” says Equip dietitian Gabriela Cohen, MS, RD, LDN. This can look like eliminating entire food groups without medical need, spending hours planning or researching meals, or avoiding social situations because food feels unpredictable or unsafe.

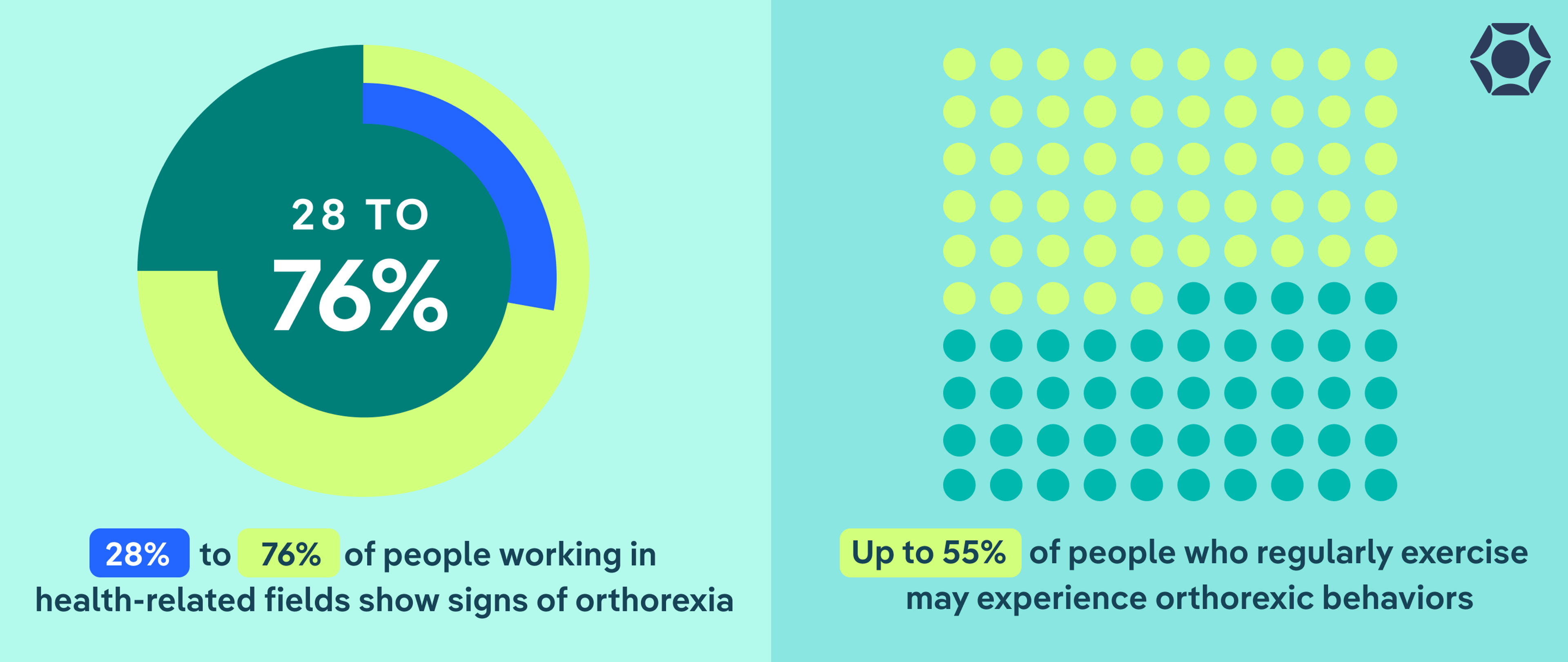

While estimates vary, orthorexia is thought to affect up to about 7% of the population—and it appears even more common in health- and fitness-focused spaces, like some competitive athletics, fitness studios, and weight loss-focused social media accounts. Studies suggest that 28% to 76% of people working in health-related fields show signs of orthorexia, and up to 55% of regular exercisers (think: athletes, weightlifters, CrossFitters, and runners)may experience orthorexic behaviors.

Many people with orthorexia start with positive intentions, like wanting to feel better physically or improve health. “We have an issue when this behavior becomes inflexible,” says Brianna Halasa, LMHC, LPCC, a licensed psychotherapist. “People start to plan their meals to the detail, cutting out entire categories of food groups or compulsively checking ingredient lists or labels.”

Because these behaviors are often praised in thinness-focused Western cultures, orthorexia can be difficult to recognize. But when food rules create distress, isolation, or harm to health, that’s a sign your relationship with food may no longer be supportive.

Is orthorexia an eating disorder?

Orthorexia nervosa is not currently a standalone diagnosis in the DSM. This lack of formal criteria contributes to confusion about whether orthorexia “counts” as an eating disorder. Many clinicians, however, recognize it as a serious and harmful pattern.

“Not only do I believe orthorexia is and should be a classified eating disorder, I think it's probably the most dangerous one,” says Ashley Isenhower, AMFT, an Equip therapist. “It’s the embodiment of diet culture and anti-fat bias.”

It also often overlaps with diagnoses like other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED), anorexia, anxiety disorders, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

How is orthorexia different from healthy eating?

| Healthy eating | Orthorexia |

| Focuses on nourishment, energy, and well-being | Focuses on food purity, rules, and “cleanliness” |

| Flexible and adaptable across different situations | Rigid, rule-based, and hard to bend |

| Allows for variety and enjoyment | Cuts out foods/entire food groups without medical need |

| Leaves room for social eating and spontaneity | Avoides eating out/eating with others due to stress |

| Food choices are guided by curiosity and balance | Food choices are driven by fear, guilt, or anxiety |

| “Less healthy” foods don’t cause distress | Breaking a rule triggers shame, anxiety, or self-criticism |

| Eating supports mental health and quality of life | Eating increases stress and preoccupation |

| Food is one part of a full, meaningful life | Food is central to identity and daily decision-making |

“Orthorexia is a focus above healthy eating to a point that it becomes more consuming and no longer healthy,” says Stephanie Kile, MS, RDN, lead registered dietitian nutritionist at Equip. “It becomes more than just healthy eating and begins to impact all areas of life.”

With healthy eating, food choices are adaptable and leave room for enjoyment and social connection. With orthorexia, food choices are governed by fear and moral judgment. Breaking a rule often leads to guilt or anxiety, and food begins to dominate daily thoughts and routines.

Put simply, healthy eating supports flexibility, nourishment, and quality of life. Orthorexia does not.

What are the signs of orthorexia?

Orthorexia can show up in many areas of daily life, not just at meals.

Myers’ experience illustrates how far-reaching the impact can be. “My life revolved around being ‘healthy,’ but I was constantly getting sick because I was not eating enough to sustain my energy needs,” she says. “I lost my menstrual cycle for many years, and orthorexia made me avoid getting help because I feared doctors would try to ‘contaminate’ me even further with medicine or chemicals.”

These signs often develop gradually, which makes them easy to overlook or dismiss as “just being disciplined.” One helpful way to understand orthorexia is to look at how it shows up across three areas: behavior, thoughts and emotions, and physical health.

Behavioral signs

With orthorexia, “food becomes a source of stress rather than nourishment,” says Halasa. “Think about someone who puts the pursuit of purity over relationships, joy, and overall well-being.” That shift often shows up through patterns like:

- Rigid food rules that go beyond medical needs, like cutting out entire food groups

- Compulsive checking of ingredient lists, nutrition labels, or sourcing details

- Spending excessive time planning meals, researching foods, or preparing food “correctly”

- Avoiding restaurants, social gatherings, or travel because food feels unpredictable

- Refusing to eat food others make or feeling the need to control every aspect of meals

- Exercising compulsively to “balance” or justify eating

- Increasing isolation as food rules limit daily life

Psychological signs

According to Kile, orthorexia can also involve “high levels of perfectionism” and “lack of ability to have freedom in eating,” even when body image concerns aren’t the primary focus. Other psychological signs include:

- Intense anxiety around eating foods deemed “unclean,” processed, or imperfect

- Guilt, shame, or self-criticism after breaking food rules

- Black-and-white thinking about food as good or bad

- Feeling morally superior—or deeply ashamed—based on food choices

- Constant mental preoccupation with food, ingredients, and eating decisions

- Difficulty being present or enjoying activities because of food-related worry

Physical signs

“If you are cutting out entire food groups without medical necessity, you won’t get adequate nutrition, which leads to deficiencies,” says Halasa. You may also notice other physical symptoms like:

- Unintended weight loss or difficulty maintaining weight

- Fatigue, dizziness, or low energy from inadequate intake

- Digestive issues such as constipation, bloating, or early fullness

- Hormonal disruptions, including missed periods or sleep problems

- Signs of nutrient deficiencies from restricted variety

- Worsening anxiety or depression as restriction increases

It’s also worth noting that someone with orthorexia may have a "normal" body mass index (BMI) and appear healthy. You can’t always tell from someone’s appearance if they’re struggling with orthorexia (or any other form of disordered eating, for that matter).

What causes orthorexia?

Orthorexia doesn’t come out of nowhere. It tends to grow gradually, often shaped by a combination of personality traits, stressors, and cultural messages about health and discipline, says Kile.

“Orthorexia is complex and shouldn’t be reduced to ‘she or he is obsessed with clean food,’” adds Halasa. For many people, food rules become a way to cope with anxiety, uncertainty, or a need for control.

Understanding these factors isn’t about blame. It’s about realizing why orthorexia takes hold—and knowing that support can help with the underlying struggles, not just the eating behaviors themselves.

Psychological factors

According to Halasa and Kile, certain mental and emotional traits can increase vulnerability to orthorexia, including:

- Perfectionism and all-or-nothing thinking

- High levels of anxiety or health anxiety

- Obsessive or compulsive traits

- A strong need for control or predictability

- History of trauma, anxiety, depression, or other eating disorders

- Poor body image, even if weight loss isn’t the original goal

Food rules can temporarily reduce anxiety, which reinforces them…until they start creating more stress than relief.

Environmental factors

Orthorexia in Today’s Culture

- Social media: Algorithms amplify extreme food rules and “clean eating” content.

- Food purity trends: Foods labeled as clean, toxic, or inflammatory create fear around eating.

- Moralized eating: Food choices become tied to discipline, worth, or virtue.

- Unregulated wellness advice: Oversimplified health claims are presented as universal truths.

- Supplement and detox culture: Products promise control, purity, or quick fixes.

- Praise for restriction: Rigid eating is rewarded as dedication or self-control.

- Diet culture in disguise: Weight loss and control are framed as wellness.

- Lack of nuance: Complex health topics are reduced to rigid rules.

“We live in a culture that praises beauty and discipline, and often confuses wellness with worth,” says Halasa. All of this can encourage orthorexic behaviors. Common examples include:

- Diet culture and the moralization of food as “good” or “bad”

- Wellness trends that equate restriction with discipline or virtue

- Social media algorithms that reward extreme eating patterns

- Exposure to misleading or oversimplified health claims

- Certain sports, careers, or communities where “clean eating” is praised

- Trauma or chronic stress, where control over food becomes a coping tool

Biological factors

Biology can also influence risk, according to Kile. Some people may be more susceptible to orthorexia due to:

- A family history of eating disorders

- Genetic predisposition toward anxiety or obsessive traits

- Digestive conditions or chronic illness that initially require dietary changes

- A history of dieting or medically supervised food restriction

What are the health risks of orthorexia?

Even when food choices look “healthy” on the surface, orthorexia can take a serious toll on both physical and mental health. And these risks don’t come from eating the “wrong” foods—instead, they stem from chronic restriction, stress, and lack of flexibility around eating.

Common health risks of orthorexia include:

- Malnutrition and nutrient deficiencies: Cutting out entire food groups without medical necessity can make it hard to meet basic nutrition needs. Over time, this can lead to deficiencies in protein, fats, vitamins, and minerals that the body needs to function properly, says Halasa.

- Hormonal disruptions: Inadequate intake can affect hormone production, leading to missed periods, fertility issues, sleep problems, and blood sugar instability, according to Kile.

- Digestive problems: Restriction can slow digestion and contribute to constipation, bloating, nausea, and early fullness, says Kile. Ironically, rigid “gut health” rules often worsen GI symptoms rather than improve them.

- Cardiovascular and metabolic effects: Malnutrition can lead to a low heart rate, dizziness, fatigue, and low blood pressure—risks commonly seen in other restrictive eating disorders, too.

- Worsening mental health: Orthorexia is closely linked to anxiety, depression, and obsessive thinking, according to Kile. The more rigid food rules become, the more food anxiety tends to increase.

- Social withdrawal and isolation: Avoiding meals with friends, family, or coworkers can strain relationships and reduce social support, which is critical for mental health and recovery, says Halasa.

- Increased risk of other eating disorders: Orthorexia can overlap with or progress into other eating disorders, including anorexia or binge eating disorder, especially as restriction intensifies.

- Delayed or avoided medical care: Some people with orthorexia distrust medical guidance, which can delay diagnosis and treatment. “My orthorexia made me really mistrust my own medical provider,” Myers says. “Instead of opting for medications to help with my chronic illness and mental health symptoms, I was determined to use diet, exercise, and supplements to manage them. I believed it wasn’t good to have anything 'artificial' in my body."

When should you seek help for orthorexia?

Many people hesitate to reach out for support because they worry their struggles with food aren’t “serious enough.” With orthorexia, that worry is especially common, especially since the behaviors are often praised or encouraged.

But distress is a meaningful signal, and you don’t have to wait until things feel extreme to ask for help. Getting support sooner can make it easier to untangle fear from food, protect your health, and move toward a more peaceful, flexible relationship with eating.

According to Kile and Halasa, it’s time to seek support if you notice:

- Food taking up a lot of mental space or causing ongoing worry

- Feeling anxious, guilty, or distressed around meals

- Pulling back from social plans, travel, or shared eating

- Experiencing physical changes like low energy, digestive issues, dizziness, or missed periods

- Struggling to eat enough to feel nourished or function well

- Feeling stuck in rules that are no longer helpful, even if you want things to change

What does orthorexia treatment look like?

Orthorexia treatment focuses on rebuilding a safer, more flexible relationship with food and health, says Halasa. This often involves practicing flexibility by doing things like slowly reintroducing foods that once felt off-limits or learning to eat in social settings without fear taking over.

Treatment also commonly addresses overlapping concerns like anxiety, OCD, or other eating disorders, which can reinforce rigid patterns. Supporting the whole person—not just changing food rules—is a key part of recovery.

That’s why treatment often involves a coordinated team, including:

- Therapists, who help address the anxiety, rigidity, perfectionism, or trauma that often drive orthorexic patterns. Therapy can support more flexible thinking, reduce fear, and build coping skills beyond food control.

- Dietitians, who work compassionately to expand food variety, challenge food myths, and restore nourishment without shame. It’s important to work with an anti-diet and/or eating disorder-informed dietitian like those at Equip for the best outcome.

- Medical providers, who monitor physical health and support recovery if complications like malnutrition or hormonal changes are present.

Because orthorexia isn’t a formal DSM diagnosis, providers may recommend using a diagnosis like OSFED, says Isenhower. This helps ensure the seriousness of the struggle is recognized and can make it easier to access appropriate care and insurance coverage.

How can I support a loved one with orthorexia?

Supporting someone with orthorexia can feel complicated. What matters most is approaching the situation with empathy, curiosity, and care.

How to start a conversation about orthorexia

You don’t need to have the perfect words. Starting from concern and observation—not criticism—can help a loved one feel safer opening up. Cohen recommends gentle, open-ended questions like:

- I’ve noticed food seems more stressful lately. How has eating been feeling for you?

- Do these habits feel supportive, or do they feel heavy or overwhelming?

- How are you feeling emotionally around food right now?

- Does anxiety around eating ever feel like it’s getting in the way of your well-being?

Avoid reinforcing harmful behaviors

Even well-meaning comments can unintentionally reinforce orthorexic patterns, says Myers. Try to avoid:

- Praising restriction or “discipline” around food

- Commenting on how healthy, clean, or pure someone’s eating looks

- Comparing your eating habits to theirs

- Turning concern into a debate about nutrition facts

Instead, center conversations on emotional health, stress levels, and quality of life.

Encourage support early and gently

If you or someone you love are showing signs of disordered eating or an eating disorder, remember that support is out there. If you’re concerned, encouraging professional support sooner rather than later can help prevent patterns from becoming more entrenched.

Equip provides tailored eating disorder treatment that includes a coordinated care team and mentors who have been through similar experiences. In treatment, trained clinicians can help you or your loved one unpack long-held beliefs about what is and isn’t “healthy,” and create space to live a life free from rigid restrictions. Schedule a free consultation to learn more.

The bottom line

Orthorexia can be hard to spot because it often looks like “doing everything right.” But when eating becomes rigid, anxiety-driven, or isolating, it can take a real toll on physical health, mental well-being, and daily life.

You don’t need a formal diagnosis—or a breaking point—for your concerns to matter. If food feels stressful, controlling, or overwhelming, that’s reason enough to seek support. With compassionate, multidisciplinary care, orthorexia recovery is possible, and you can rebuild a more flexible, peaceful relationship with food and health.

FAQ

Is orthorexia a type of OCD?

OCD and orthorexia are not the same, but the two can overlap. Many people with orthorexia experience obsessive thinking, compulsive behaviors, or high anxiety around food. That’s why treatment often addresses co-occurring anxiety or OCD traits alongside eating behaviors.

What happens if orthorexia goes untreated?

Over time, orthorexia can lead to malnutrition, hormonal disruptions, digestive issues, worsening anxiety or depression, social isolation, and increased risk of other eating disorders. Because the behaviors are often praised, many people delay getting help, which can make recovery harder.

Is orthorexia in the DSM?

No. Orthorexia nervosa is not currently a standalone diagnosis in the DSM. However, many clinicians recognize it as a serious disordered eating pattern. Providers may use a diagnosis like OSFED for people struggling with orthorexia to ensure symptoms are taken seriously and treatment is accessible.

Atchison, Anna E, and Hana F Zickgraf. “Orthorexia nervosa and eating disorder behaviors: A systematic review of the literature.” Appetite vol. 177 (2022): 106134. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2022.106134

Balasundaram, Palanikumar, and Prathipa Santhanam. “Eating Disorders.” National Library of Medicine, StatPearls Publishing, 2023, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567717/.

Carlson, Jennifer L, and Diana C Lemly. “Medical Considerations and Consequences of Eating Disorders.” Focus (American Psychiatric Publishing) vol. 22,3 (2024): 301-306. doi:10.1176/appi.focus.20230042

Costandache, Gina I et al. “An overview of the treatment of eating disorders in adults and adolescents: pharmacology and psychotherapy.” Postepy psychiatrii neurologii vol. 32,1 (2023): 40-48. doi:10.5114/ppn.2023.127237

Hafstad, Stine Marie et al. “The prevalence of orthorexia in exercising populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Journal of eating disorders vol. 11,1 15. 6 Feb. 2023, doi:10.1186/s40337-023-00739-6

Horovitz, Omer, and Marios Argyrides. “Orthorexia and Orthorexia Nervosa: A Comprehensive Examination of Prevalence, Risk Factors, Diagnosis, and Treatment.” Nutrients vol. 15,17 3851. 3 Sep. 2023, doi:10.3390/nu15173851

McInerney, Ellie G et al. “A Systematic Review on the Prevalence and Risk of Orthorexia Nervosa in Health Workers and Students.” International journal of environmental research and public health vol. 21,8 1103. 21 Aug. 2024, doi:10.3390/ijerph21081103

Yılmaz, Hamdi et al. “Association of Orthorexic Tendencies with Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms, Eating Attitudes and Exercise.” Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment vol. 16 3035-3044. 14 Dec. 2020, doi:10.2147/NDT.S280047