- Family-based treatment is the gold standard for treating eating disorders in young people. It can be used in cases of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, bulimia binge eating disorder (BED), avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) and other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED).

- This approach to treating eating disorders among children, adolescents, and young adults is centered around outpatient care that actively engages parents or caregivers in the treatment.

- FBT is not limited to traditional nuclear families. It can be successfully used with blended families, separated families, or any caregiving system involved in a child’s daily life.

When your child is struggling with an eating disorder, finding a treatment option that feels like the right fit can seem daunting and overwhelming. As a parent or caregiver, you may also be hesitant to send your child away to a residential treatment facility that distances you from the recovery process. The good news is there is another option: Family-based treatment (FBT)

One of the leading evidence-based approaches available, FBT is the gold standard treatment for young people with eating disorders, including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFEFD). This form of therapy allows children to remain living at home throughout the recovery process and actively engages parents or caregivers in treatment.

For JD Ouellette, a San Diego mom and Equip's Director of Lived Experience, FBT played a critical role in saving her daughter Kinsey who developed anorexia nervosa in late 2011, as a senior in high school.

While Ouellette says her daughter’s eating disorder was “a terrifying situation,” the family was heartened and relieved that there was an available, proven successful treatment modality “that did not involve sending our daughter away."

"This was critical for us, because our strong instinct was always to lean into our closeness as a family and stand united when tough things happened," says Ouellette. "I knew that treatment for anorexia would be incredibly hard and that meant we needed to do it together."

But what exactly does FBT involve? In this guide we'll provide a comprehensive look at FBT, including a clear breakdown of how (and why) it works, what participants can expect, and how Equip builds upon the FBT model.

What is family-based treatment (FBT)?

Family-based treatment, or FBT, is an approach to treating eating disorders that's proven incredibly successful in helping children, teens and young adults to gain weight. This approach to treating eating disorders is also often referred to as the Maudsley Method because the treatment was developed at Maudsley Hospital in London, England.

Considered the gold standard for eating disorder treatment, FBT can be used in cases of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, bulimia, binge eating disorder (BED), avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) and other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED). Caregivers play a key role in this approach to treatment—in fact, they’re the primary change agent in the outpatient treatment process.

"Family-based treatment is a collaborative approach to care that brings the whole family into the healing process," says Samantha Bickham, LMHC, CEDS, QS, owner and certified EMDR therapist at Calming Tides Counseling. "Treatment works best when the people who have the most consistent influence and connection with the [patient] are actively involved."

This line of thinking is a significant break from past theories about treating eating disorders, which often placed blame for the disorder on family dysfunction.

Equally importantly, families come in all shapes and sizes and FBT is not limited to traditional nuclear families. It can be successfully used with a variety of different family make-ups including members of blended families, separated families, or any caregiving system involved in a child’s daily life.

"Supports can be parents, but supports can also expand to extended family, friends and neighbors. Each family is different and the treatment can be adapted to fit the individual family and patient's needs," says Carol Brown, an Equip therapist.

While experts have widely endorsed FBT as the best treatment approach for young people, a variation of this treatment known as family-based treatment for transition age youth (FBT-TAY) is also available for older patients (ages 18 to 26) who can benefit from their family’s or caregiver's support in recovery.

There's also a specific FBT approach that's been adapted for children impacted by Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID). This treatment includes many of the same methods and interventions as standard FBT, but also includes various departures such as allowing a child struggling with ARFID to be a more active participant in their own treatment and doing so earlier on during the treatment process.

Beliefs underlying FBT

There are several key beliefs or tenets that form the basis for FBT and its method of supporting your child's recovery from an eating disorder. They include:

- An agnostic view of the causes behind the illness: The central idea behind this first tenet is that FBT "does not focus on exploring causes of the illness, but instead aims to engage the family as a resource to bring about early behavioral change," says a 2022 article on the tenets of FBT published in the Journal of Eating Disorders. One of the most important takeaways about the agnostic approach is that it does not blame you, the parent or caregivers, for causing the disorder, which is a notable and important difference from historic ways of treating eating disorders.

- Therapists take a non-authoritarian stance in the treatment: Another core element of FBT is that the therapist or medical professionals involved typically act more like expert consultants who are the eating disorder and treatment experts. While these professionals are of course, actively engaged, they do not tell parents or caregivers what to do. Instead, "decisions about how to implement treatment are left up to the parents," explains the 2022 Eating Disorders article..

- Parents are empowered to bring about the child's recovery: Adding to the previous point, it's you as the parent or caregiver who's empowered to spearhead your child's recovery during FBT. After all, you are the expert when it comes to knowing the patient and your family.

- The eating disorder is separated from the patient and externalized: Another important feature of FBT is that the eating disorder or illness is separated from the child. What does this mean exactly? When a child does not eat, it's not because they are trying to be difficult or stubborn. Nor are they even really doing it on purpose. The behavior is the result of the fact that the child is still controlled by a powerful eating disorder. And that disorder has the power to influence thoughts, feelings and actions.

- Treatment takes a pragmatic approach: During FBT, the treatment is focused on eating and weight restoration first, knowing that ED behaviors naturally resolve as patients become nourished.

What’s the difference between family therapy and family-based treatment?

| FBT | Family Therapy | |

| Focus | FBT targets eating disorder symptoms first. Does not presume any underlying problems within the family. | Focuses on the relationships and interactions within a family unit. |

| Who leads work | Families or caregivers take on a central role in recovery, supported by regular meetings with trained healthcare professionals. | A therapist plays lead or key role as a facilitator. |

| Primary goal | Empowering family members to renourish their loved one, including providing families with the knowledge, skills, and strategies they need to fight the eating disorder at home. | Strengthening the family as a unit, improving family dynamics or addressing conflicts. |

Given how similar the terms FBT and family therapy sound, there's (understandably) confusion surrounding the difference between these two treatment models. While there are some similar elements, these two forms of treatment are not the same. As the table above illustrates, there are different goals, methods and even focuses for FBT and family therapy.

"Family therapy is a broad term and encompasses many different styles and approaches to build communication skills, explore family patterns and improve family relationships. In traditional family therapy, the family is viewed as the patient and therapy focuses on strengthening the family as a unit," explains Carol Brown.

FBT, on the other hand, has a very targeted and specific goal of improving eating disorder symptoms. While the therapy does incorporate the family, the treatment sessions are highly structured and goal-oriented. That includes following a behavior-focused, agnostic approach that doesn’t prioritize getting to the root causes behind the illness, but instead works to return your child to a nourished state—knowing that behaviors related to the disorder will resolve as recovery takes place.

Which eating disorders can be treated with FBT?

FBT supports young people of all body sizes, identities, and family structures. And while it was initially developed specifically to treat anorexia, it has since been shown to be effective in treating all types of eating disorders, including:

- Anorexia nervosa

- Bulimia nervosa

- Binge eating disorder (BED)

- Avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID)

- Other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED).

How does FBT work?

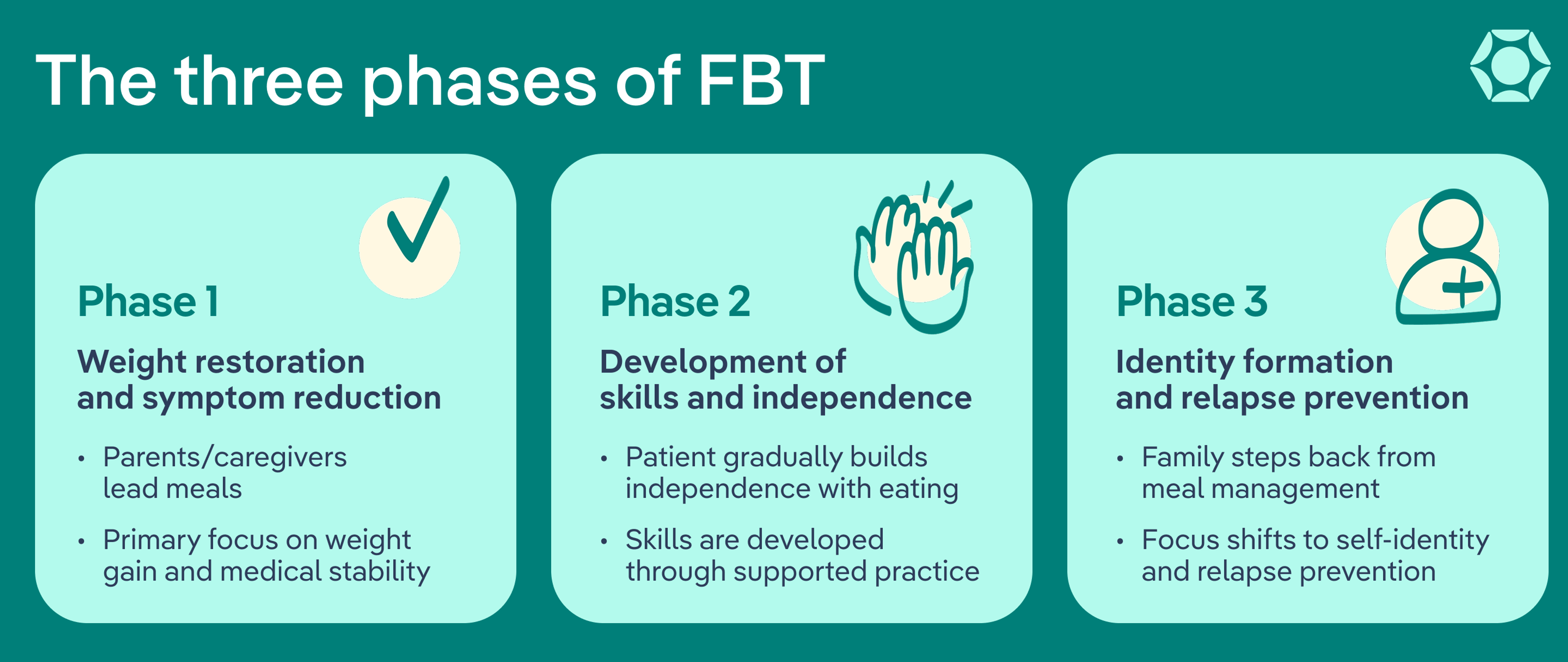

With families or caregivers taking the lead, the FBT approach to treating an eating disorder moves through three key phases:

- Reduction of symptoms and weight restoration (when needed)

- Development of skills and independence

- Identity formation and relapse prevention

Let's take a closer look at what each of those phases involves.

Phase 1: Weight restoration and symptom reduction

During phase 1 of FBT, the patient's parents, caregivers, or supports are in charge of plating and monitoring meals and supporting the patient in reducing eating disorder symptoms.

During this phase, the family will attend sessions with a trained health professional. Here, you’ll focus on empowering the patient’s support at home—that means managing symptoms as well as providing skills to cope with challenges that show up during or after mealtimes. Weight restoration is also a key focus of this phase when needed—along with resolving any other health concerns that might be related to the patient’s eating disorder symptoms.

Phase 2: Development of skills and independence

Moving on to phase 2, at this point, the patient should be ready to start building their independence surrounding eating. Also during this phase, support sessions with a trained health professional focus on building skills to help the patient slowly regain independence around eating with the continued support of parents or caregivers. "This can look like the patient practicing independently plating or preparing meals with initial oversight from supports that is slowly phased out," explains Carol Brown.

Phase 3: Identity formation and relapse prevention

This is the final phase of FBT. At this point in treatment, if the patient has reached a healthy weight and eating disorder behaviors have subsided, the family or caregivers are often encouraged to be completely hands-off when it comes to managing meals, explains Sharonda Brown, MA, BS, LPC-S, NCC, who specializes in eating disorders and FBT.

"This allows the adolescent or young adult an opportunity to build trust and learn who they are by making dietary choices that are best for their health and well-being," explains Sharonda Brown.

"We also discuss creating a space of normalcy for the family where the eating disorder is no longer the focus," Brown adds.

Additional central features of phase 3 include identity formation and relapse prevention. Identity formation involves the patient exploring their identity beyond the eating disorder that has defined their daily life. This might include engaging in hobbies, reconnecting with friends, and even patients choosing their meals based on their own tastes and desires, rather than calories.

This phase might also include having a meal with friends (instead of family), especially if friends were missed during treatment.

Relapse prevention, meanwhile, involves therapists working with you and your child to develop long-term strategies that can be used as a guide to get back on track, should recovery become compromised at any point.

This typically includes establishing a formal plan that's written and can be referred to if there are slip-ups or challenges after treatment ends, says Sharonda Brown.

"So, this looks like identifying triggers and stressors beforehand, as well as thoughts, beliefs, or habits that can potentially provoke a binge, purge, or restriction," Brown explains. "Alongside those, would be remedies or solutions to suppress urges or decrease the use of eating disorder behaviors."

What to expect as a parent or caregiver

For the parents or caregivers who play a key role in FBT, the journey can be daunting, marked by a rollercoaster of emotions ranging from fear to grief, exhaustion, and frustration. FBT also involves a significant time commitment, along with strict meal structure and regular, ongoing attendance of appointments with a healthcare professional.

It's not unusual for caregivers to be overwhelmed or even surprised at how much commitment and work is involved. It's a process that can feel daunting and difficult because dealing with illness is hard, but remember: it's not permanent and the process becomes less intense and time-consuming as your loved one moves toward lasting recovery.

"It was without a doubt the hardest thing I, and we, have ever done," says Ouellette, who (along with her husband, as often as was possible) spent 12 hours a week participating in an outpatient treatment program with their daughter.

The FBT process and renourishing her daughter also required that Ouellette learn to cook in ways that ensured every meal and snack had maximum possible fat and calories. Even harder than meal preparation was getting her daughter (who was terrified of eating anything), to consume the food Ouellette was preparing day after day.

"It started with a level of supervision of her that was reminiscent of the toddler years, and required my own strong will, skill, finesse, and ultimately raw determination to get her to eat," Ouellette recalls. "Her reaction to food was very much a 'fight' reaction in the 'flight, fight, freeze' response to terror. Her brain was literally processing food as a threat to her life."

The key takeaway for parents or caregivers however, is that the effort is always worth it, as recovery is entirely possible. What's more, FBT gets less daunting after the initial push. And finding and maintaining a support network is a critically important way for families or caregivers to navigate the ups and downs of the process.

"It can be demoralizing so it is vital to connect with other families so you know this is normal and can be temporary if you keep going," says Ouellette. "Hope is critical and that's why you need to hear from parents and people in full recovery."

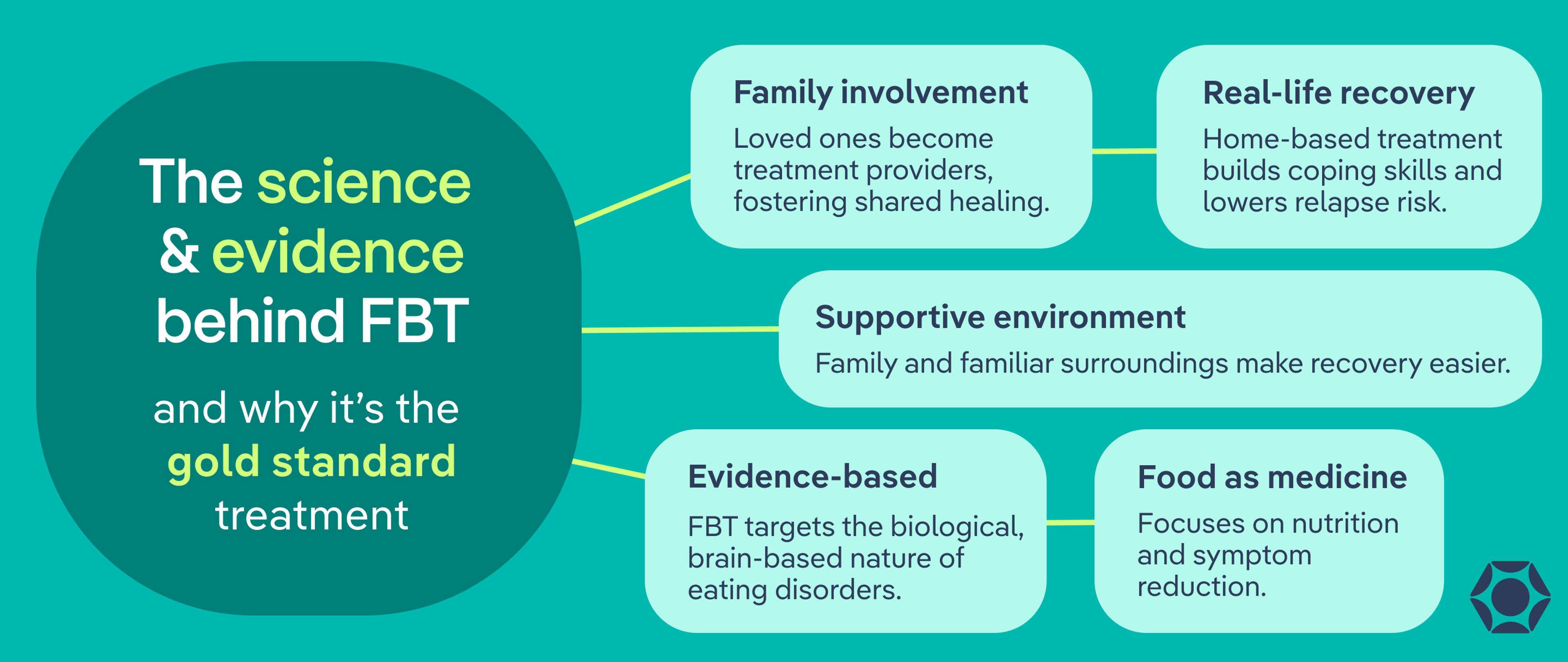

What makes FBT so effective?

There are a variety of reasons why FBT is so incredibly effective, not the least of which is the psychological benefits of family or caregiver involvement in the treatment process. FBT combines the most recent evidence-based clinical research with the sheer power of family.

"FBT is effective because it takes those who love you and makes them your treatment providers," says Sharonda Brown. "So often, families are separated from their loved ones’ treatment. With FBT, families get firsthand knowledge of what an eating disorder really is and how it affects everyone involved. It’s almost like healing from the same wound together."

In addition, eating disorders are biological, brain-based illnesses, and FBT’s focus on nutritional rehabilitation and symptom reduction acknowledges that fact. Armed with the knowledge that food is medicine, families can start to renourish their loved one even when the eating disorder is causing resistance and lack of motivation.

FBT also helps patients stay in recovery because treatment is happening in the midst of the stressors and challenges of everyday life. Recovering at home means that patients are actively and continually building the tools and coping skills they need all along the way, reducing the risk of relapse that can occur during a transition from a separate treatment setting back into real life.

Still, as a parent or caregiver who is charged with leading what can be an often difficult recovery process, it's natural to worry that the process may harm your relationship with your child. The resistance a child exhibits however, is normal and has nothing to do with feelings about the parent or caregiver.

Ouelette says the eating disorder can cause your child to behave outside their values. "You are pouring everything into fighting for your child, and what you often get back in the beginning is sneering and snarling and name calling," explains Ouelette. "I had to remind myself all day that this was not my actual daughter and my actual daughter was depending on me to save her. And over time that is exactly what happened."

Not only did Ouellette's daughter fully recover (she now loves food more than before she got sick and eats with gusto), the family is even closer than before.

The bottom line: Eating disorder recovery is hard work, but undergoing treatment can be that much easier when surrounded by family members, friends, and the comfort of home.

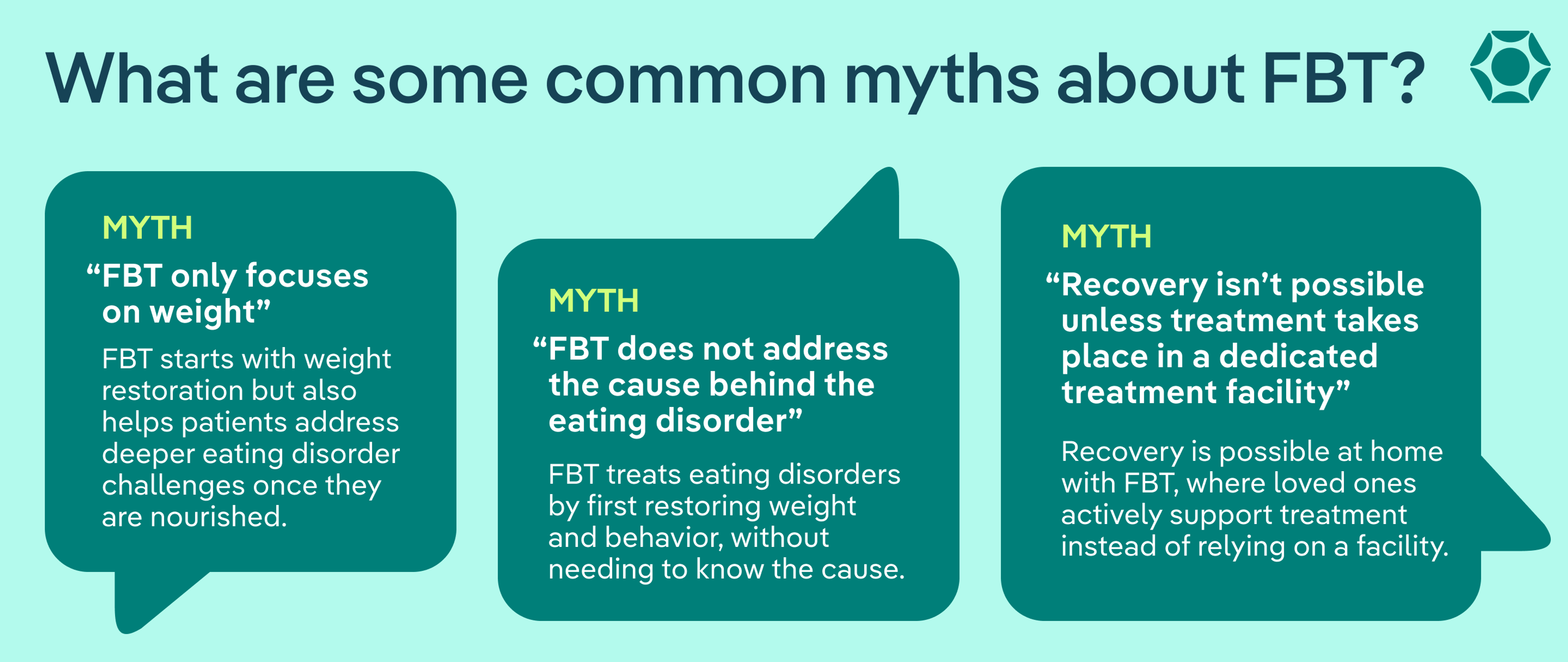

What are common misconceptions about FBT?

There continues to be confusion, misconceptions or myths surrounding FBT and what it involves. Here are some of the most common myths.

Myth #1: Only specific types of families can benefit or use FBT

This is not true. Families and caregivers come in all forms and FBT can be used effectively by any type of household. That includes single-parent homes, blended families, divorced households, foster care families and more. An Equip study published in 2025 underscores this point. It found that FBT works effectively for families of all different configurations and demographics.

"While FBT literally stands for family-based therapy, we believe that the word family can be interchanged for supports, and supports are individualized for each person in recovery," explains Carol Brown. "As an FBT therapist, I've worked with extended families, grandparents, cousins, aunts, schools, in-home mentors, friends, neighbors, and partners. All of these supports can help support patients navigate challenging meals. FBT is just as effective when working with these supports. We believe it really does take a village."

Myth #2: FBT does not address the cause behind the eating disorder

FBT is known as an "agnostic" approach to treatment, meaning it works no matter what is causing the patient's eating disorder. But that doesn't mean it ignores the factors that might be contributing to the disorder.

However, FBT is based on the belief that an eating disorder can be effectively treated: 1) without knowing the exact cause, and 2) by first renourishing the patient and reducing active engagement in disordered behaviors. When a patient's body and brain are undernourished it makes addressing other issues harder, including the causes behind the eating disorder.

"Once the first two phases of family-based treatment are completed, the third phase can allow space for other areas of concern to be looked into," says Bickham. "Research has shown that psychological symptoms such as feelings of depression improve once weight is restored."

Myth #3 FBT “only focuses on weight”

While FBT initially does focus on weight restoration, the purpose of this approach is to help support patients in processing some of the more challenging aspects of their eating disorder after their body is fully nourished, says Brown.

"As a therapist I often liken trying to challenge eating disorder thoughts in a malnourished body to trying to write a complex science research paper while sleep deprived—it doesn't work very well," Carol Brown explains. "FBT helps the patient tackle the challenges related to malnourishment as an initial focused goal."

Once there is a significant and noticeable improvement in the rigid, obsessive thoughts, mood dysregulation and motivation associated with eating disorders, and are fully nourished, patients are better able to tackle the other issues associated with eating disorders, adds Brown.

Myth #4: Recovery isn’t possible unless treatment takes place in a dedicated treatment facility

Because FBT allows patients to recover in the comfort and familiarity of their own environments, it eliminates the need to remove patients from their everyday lives and empowers loved ones to play an active role in supporting treatment. Additionally, through FBT, parents and caregivers get the opportunity to build confidence in their ability to care for their child, which can help ensure success in recovery. In many ways, FBT is effective because it doesn’t happen in a dedicated treatment facility. Check out these tips for parents in FBT.

When might FBT not be a good fit?

While FBT is an incredibly effective evidence-based approach to treating EDs, it may not be right for everyone. There are some situations when this type of treatment may not be the best option, including when there may be safety concerns related to the patient and when there is limited capacity among families or caregivers to participate in treatment.

"FBT might not be a good fit if the patient is medically compromised and needs high levels of medical oversight/hospitalization," explains Carol Brown. Know that inpatient hospitalization is generally a short-term solution to help stabilize a patient; then, they’ll move into longer-term ED treatment, with FBT as a solid next step after inpatient.

There are also occasionally times when significantly high levels of internal family conflict (unrelated to the eating disorder) can be a barrier to successful implementation of FBT. However conflict itself does not necessarily mean FBT cannot be implemented.

The time commitment that this type of treatment involves may also not be possible for every family. Particularly during the beginning phases of treatment, it is important that family members are able to stay present at home in order to reestablish weight and regulate meals, notes Bickham. This type of intensive commitment can lead to financial stress and the needs of other family members being overlooked.

When there are questions about whether FBT can be effective, it's best to consult an eating disorder therapist in order to help make an informed decision. Determining that FBT is not right in your situation does not imply any sort of failure or that the treatment approach you proceed with is somehow less effective or promising.

How has Equip built upon FBT?

Helping a loved one recover from an eating disorder is no small feat. Many families find they need more support than weekly sessions with an FBT therapist in order to achieve full recovery. Equip builds on the foundation of FBT by making treatment fully virtual and adding the wraparound support of a dedicated 5-person care team, which includes a substantial mentorship component. Each family participating in Equip's process gets both a peer mentor for the patient and a family mentor for the parents.

In addition, because body image can be such a challenge for someone recovering from an eating disorder, Equip enhances traditional FBT by offering an evidence-based body image program for patients. Building body image resilience and body empowerment strengthens recovery and reduces the risk of relapse.

With virtual treatment, patients and families have more time to focus on life outside of the eating disorder, because we know that lasting recovery comes from building a life worth living. If you'd like to learn more about how FBT could work for your family, schedule a consultation.

The bottom line

Eating disorders are a life-threatening condition, but the good news is that recovery is entirely possible—for children and teens as well as adults. FBT offers one of the most effective approach for young people in achieving this critical goal. It does so by combining evidence-based clinical research with the power of family, offering families or caregivers a path to renourish their loved one, help them escape from the grip of their eating disorder, and reclaim their life. If you have questions about FBT, reach out to Equip for a consultation to learn more about how we can help.

Frequently asked questions (FAQs)

Is FBT evidence-based?

Yes, FBT is evidence-based. There is a great deal of research confirming the effectiveness of FBT in treating eating disorders. It has consistently been shown to be a first-line evidence-based treatment (EBT) that can help interrupt eating disorder behavior in young people.

What are the three phases of family-based treatment?

With families or caregivers taking the lead, the FBT approach to treating an eating disorder moves through three key phases. They are reduction of symptoms and weight restoration (when needed); development of skills and independence; and identity formation and relapse prevention.

Does FBT work for anorexia?

Yes, FBT was initially developed specifically to treat anorexia. It has since been shown to be effective in treating all types of eating disorders, including bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder (BED), Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) and Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder (OSFED).

GRANGE, DANIEL LE. 2005. “The Maudsley Family-Based Treatment for Adolescent Anorexia Nervosa.” World Psychiatry 4 (3): 142 https://bit.ly/3NcrGD1

Datta, Nandini, Kelsey Hagan, Cara Bohon, May Stern, Bohye Kim, Brittany E. Matheson, Sasha Gorrell, Daniel Le Grange, and James D. Lock. 2022. “Predictors of Family‐Based Treatment for Adolescent Eating Disorders: Do Family or Diagnostic Factors Matter?” International Journal of Eating Disorders 56 (2) https://bit.ly/3LcvyDz

Egan, Christian. 2024. “Family Therapy vs. Family-Based Therapy: Key Differences - Influence Therapy & Coaching.” Influence Therapy & Coaching. October 12, 2024. https://bit.ly/49pCogW

Forsberg, Sarah, Sasha Gorrell, Erin C. Accurso, Claire Trainor, Andrea Garber, Sara Buckelew, and Daniel Le Grange. 2021. “Family-Based Treatment for Pediatric Eating Disorders: Evidence and Guidance for Delivering Integrated Interdisciplinary Care.” Children’s Health Care 52 (1): 1–16. https://bit.ly/4sI2IvM