- Research shows a strong link between social media use and increased risk for body dissatisfaction, disordered eating, and eating disorders in kids.

- Algorithms amplify appearance-focused and restrictive content, often pushing vulnerable teens into progressively more extreme diet or fitness material.

- Comparison culture, filters, and coded pro-eating disorder content on social media normalize unattainable body standards.

- Certain groups—including LGBTQIA+ youth, athletes, neurodivergent teens, and high-achieving students—face elevated risk.

- Parents can reduce harm through open communication, media literacy, feed curation, and early intervention when warning signs appear.

The connection between social media and eating disorders can feel scary for any parent. You see your child scrolling, hear about trends like “thinspo” or “what I eat in a day,” and start to wonder: Is this just normal teen behavior, or something that could hurt them?

“Social media increases the risk for eating disorders because it turns comparison into a constant, 24/7 passive activity,” says Adriana Lindenfeld, MA, EdM, a therapist at Equip. “Teens are exposed to filtered bodies, curated diets, and extreme fitness routines that are presented as ‘normal,’ and the brain begins to interpret those repeated images as truth.”

In this guide, we’ll walk through how social media influences body image and eating, which kids are most vulnerable, early warning signs to watch for, and what you can do right now to help your child navigate the online world more safely and confidently.

How are social media and eating disorders linked?

Research consistently shows a clear connection between eating disorders and social media, especially for kids and teens. Studies have found that higher time spent on platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube is linked to increased body dissatisfaction, dieting behavior, appearance comparison, and symptoms of eating disorders.

This doesn’t mean social media causes eating disorders on its own. But it can significantly increase risk for children who already have underlying vulnerabilities—which, during adolescence, includes a lot of kids.

The teen brain is especially sensitive to social feedback, comparison, and belonging, according to Michael Wetter, PsyD, ABPP, FAACP, a clinical psychologist who specializes in eating disorders. At the same time, many kids are still learning how to spot edited images, sponsored posts, or unhealthy “wellness” content. When likes, comments, and views become a kind of social currency, teens can start tying their self-worth to how they look on and offline, he says.

Weight stigma and diet culture amplify this pressure. Social media is filled with messages linking thinness to health, discipline, success, or morality, says Wetter. Over time, these subtle cues can quietly shape how kids think about their bodies and eating.

“What a child sees is not simply ‘someone looking good in a photo,’ but an implicit message about what is normal, expected, and valued within their peer group and the broader culture,” says Wetter. When those messages center on narrow, edited beauty standards, it becomes harder for teens to develop a realistic, positive,, compassionate body image.

Why social media can increase eating disorder risk

Certain features of social platforms interact with the developing teen brain in ways that can quietly increase vulnerability to eating disorders. These risks often build gradually, through everyday scrolling rather than through obviously harmful content.

“What begins as mild curiosity can become a highly reinforcing digital loop where the platform continuously provides material that shapes the child’s beliefs about their body, their value, and what they must do to be accepted,” explains Wetter. Here are some of the most important mechanisms behind that process.

Comparison loops

Social media invites constant comparison, often right at the moment when teens’ bodies are already changing quickly and unevenly because of puberty. As some peers develop earlier or later than others, those natural differences can feel magnified online. Teens see carefully chosen photos and videos of peers, influencers, athletes, and celebrities—almost all filtered, posed, or edited to present a highly unrealistic version of what bodies “should” look like, says Wetter.

“Young people begin to believe that their natural appearance is abnormal or inferior, even though the images they are comparing themselves to are digitally altered,” he explains. “This comparison can become automatic, leading to chronic dissatisfaction with one’s body, withdrawal from social activities, avoidance of situations involving food, and an escalating internal narrative of shame.”

Filters, editing tools, and AI-generated bodies

Today’s filters and editing tools—now powered by increasingly advanced AI—can dramatically change faces and bodies with the tap of a finger. Waistlines shrink, muscles sharpen, skin smooths, and proportions shift toward narrow “ideal” standards that don’t reflect real bodies.

When kids are repeatedly exposed to these altered images, their sense of what bodies normally look like gets distorted, says Wetter. This makes it easier for young people (both children and teens) to believe they should look different than they do, even when their bodies are healthy and developing exactly as expected. That gap between “real me” and “online bodies” fuels frustration, shame, and body dissatisfaction.

Algorithm amplification

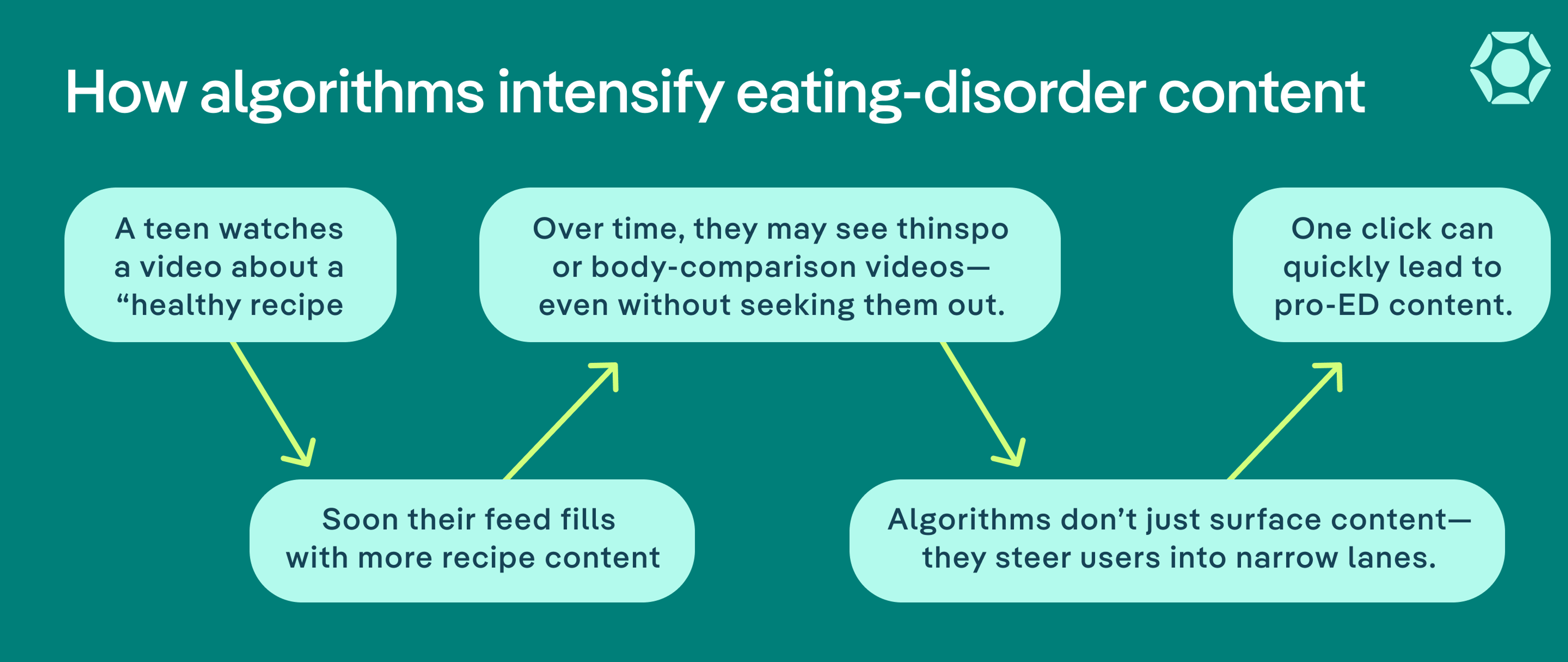

One of the most concerning aspects of social media is how quickly algorithms intensify content exposure, often without a teen realizing it’s happening. Platforms are designed to feed users more of whatever keeps them engaged, so one harmless click can rapidly shift a teen’s feed toward more extreme or appearance-focused material. Research suggests this is especially true on Instagram and Snapchat.

For example, a teen might start by watching a video about a “healthy recipe.” Soon their feed fills with more recipe content, which gradually shifts toward low-calorie or weight-loss meals, fasting tips, and body transformation posts. Over time, this can lead to exposure to thinspo, pro-ED messaging, or videos comparing body shapes, even though the teen never searched for this content intentionally.

“Algorithms don’t just show content but funnel users into narrower tunnels,” says Lindenfeld. “One innocent click on ‘healthy recipes’ can quickly spiral into weight-loss hacks, extreme dieting, and even pro-ED messaging.”

That can be the spark that triggers restrictive eating, calorie fixation, bingeing, purging, or compulsive exercise, adds Wetter.

Hidden or coded pro-eating disorder content

Some online communities that promote eating disorder behaviors actively evade detection. Hashtags shift constantly, wellness-coded language replaces direct mentions of restriction, and accounts frame disordered behaviors as discipline, “clean eating,” or self-improvement.

Because this content doesn’t always look obviously harmful, teens—and even parents—may not realize they’re being exposed to messaging that encourages starvation, purging, or compulsive exercise. What appears on the surface as motivational or healthy can quietly reinforce eating disorder thinking underneath.

Diet, fitness, and “healthy lifestyle” trends

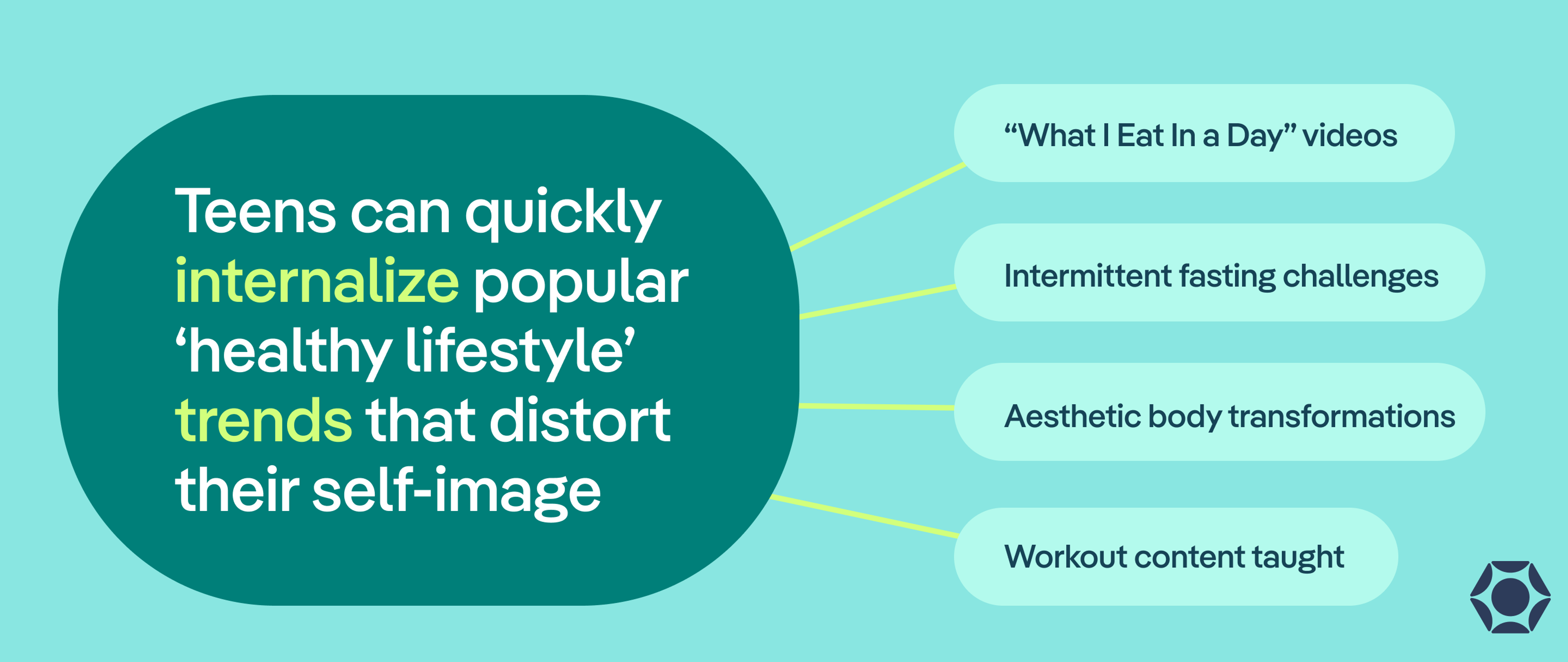

Many popular trends feel harmless—some are even genuinely well-meaning—but still pose risk for vulnerable teens. According to the experts, common trends include:

- “What I Eat In a Day” videos (WIEIAD) that document every meal

- Intermittent fasting challenges

- Aesthetic body transformation videos

- Workout content taught

Fitspo and thinspo (fitspiration and thinspiration) content also focus heavily on achieving certain body shapes rather than supporting overall well-being, reinforcing the idea that appearance is the ultimate marker of success or worth.

“Teens can internalize these ideas quickly, adopting patterns that look like clean eating, fitness motivation, or lifestyle optimization but are actually early manifestations of eating disorders,” says Wetter.

Who’s most at risk?

Any child can be affected by social media pressure. But some kids are more vulnerable than others due to developmental stage, personality traits, or life experiences.

Lindenfeld and Wetter recommend staying attentive to changes in eating, body image, or emotional well-being for the following groups:

- Teens and preteens: Adolescence is the most common time for eating disorders to emerge. Rapid physical changes, a need for peer approval, and constant exposure to appearance-focused content can shape body image.

- Girls: Girls are diagnosed with eating disorders more often than boys, in part due to stronger cultural pressure to be thin and appearance-focused content on social media. Boys may also be more likely to go undiagnosed due to stigma.

- Perfectionistic or high-achieving kids: Kids who hold themselves to very high standards may be more vulnerable to messages that frame food restriction or extreme exercise as discipline, control, or self-improvement. Diet culture ideals can blend easily with perfectionistic thinking.

- LGBTQIA+ youth: LGBTQIA+ teens have higher rates of body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms, often due to stress, identity pressures, or feeling unsafe expressing themselves offline. While social media can provide community, it can also amplify appearance comparison.

- Neurodiverse youth: Autistic and ADHD youth may be more prone to rigid routines, hyperfixation, or repetitive content loops, especially when combined with sensory sensitivities or anxiety around food.

- Athletes and dancers: Performance cultures that emphasize appearance, leanness, or weight loss in teens can normalize restrictive eating or compulsive training. Social media adds constant visual comparison to already high-pressure environments.

- Kids experiencing major transitions: Children navigating puberty, school changes, or family stress may turn to social media for comfort, control, or validation. During these vulnerable periods, appearance pressure and diet culture content can have an even stronger impact.

What are early warning signs parents should watch for?

Eating disorders are often hidden illnesses. Many kids and teens work hard to conceal their behaviors—they may sneakily skip meals, exercise in private, or change their eating habits away from home. You may not see obvious red flags at first, and that doesn’t mean you’re missing something or doing anything wrong.

The most important tool you have is your intuition. If something about your child’s relationship with food, movement, or their body feels off, it’s worth paying attention even if you can’t point to a single dramatic change. Subtle shifts that persist over time are often more telling than one big sign.

Here are some common early warning patterns to watch for.

Behavioral signs

Keep an eye out for changes in daily habits or routines that weren’t there before. According to Lindenfeld, that can look like:

- Skipping meals or suddenly avoiding family meals

- Cutting out entire food groups without a medical reason

- Creating rigid food “rules” (only eating certain foods or at specific times)

- Obsessively reading nutrition labels or tracking calories

- Exercising excessively, secretly, or feeling intense guilt for missing workouts

- Frequently watching diet, fitness, or WIEIAD content

- Frequent body checking (constant mirror checking or body pinching)

- Visiting the bathroom immediately after meals

Emotional signs

These are changes in mood or thought patterns related to food or body image, including:

- Increased anxiety or irritability around meals or food events

- Strong fear of weight gain or intense dissatisfaction with their body

- Talking negatively about their appearance

- Perfectionistic self-criticism or all-or-nothing thinking

- Withdrawn mood, low energy, or increased secrecy

Social signs

These show up in how your child interacts with others. For instance:

- Pulling away from friends or family

- Avoiding social situations centered around food

- Skipping parties, practices, or outings they once enjoyed

- Increased isolation or time alone in their room or on social media

If you’re noticing several of these patterns and aren’t sure what they mean, taking Equip’s free eating disorder screener can be a helpful way to gauge next steps and options for support.

Can social media be a positive or supportive space, too?

Social media isn’t all harmful. For many kids and teens, it can also offer creativity, community, education, and connection—especially those who feel isolated or misunderstood in their offline lives.

“Following body-neutral or recovery-oriented creators, accounts that promote diverse body types, and evidence-based mental health content can counter the pressure of idealized images,” says Lindenfeld. “A curated feed can help replace harmful messages with compassion, realism, and connection.”

Social platforms can be particularly meaningful for LGBTQIA+ and neurodivergent youth. Online communities often provide safe spaces to explore identity, find validation, and connect with peers when in-person support feels limited or unavailable. That sense of belonging can reduce loneliness, one of the emotional drivers frequently tied to disordered eating.

How parents can keep their kids safe on social media

You don’t have to become a tech expert or monitor every scroll to help protect your child online. What matters most is building trust, staying involved, and creating an environment where your child feels safe talking about what they’re seeing and feeling.

Here are evidence-informed ways to help keep kids safer while they navigate social media:

Build media literacy together

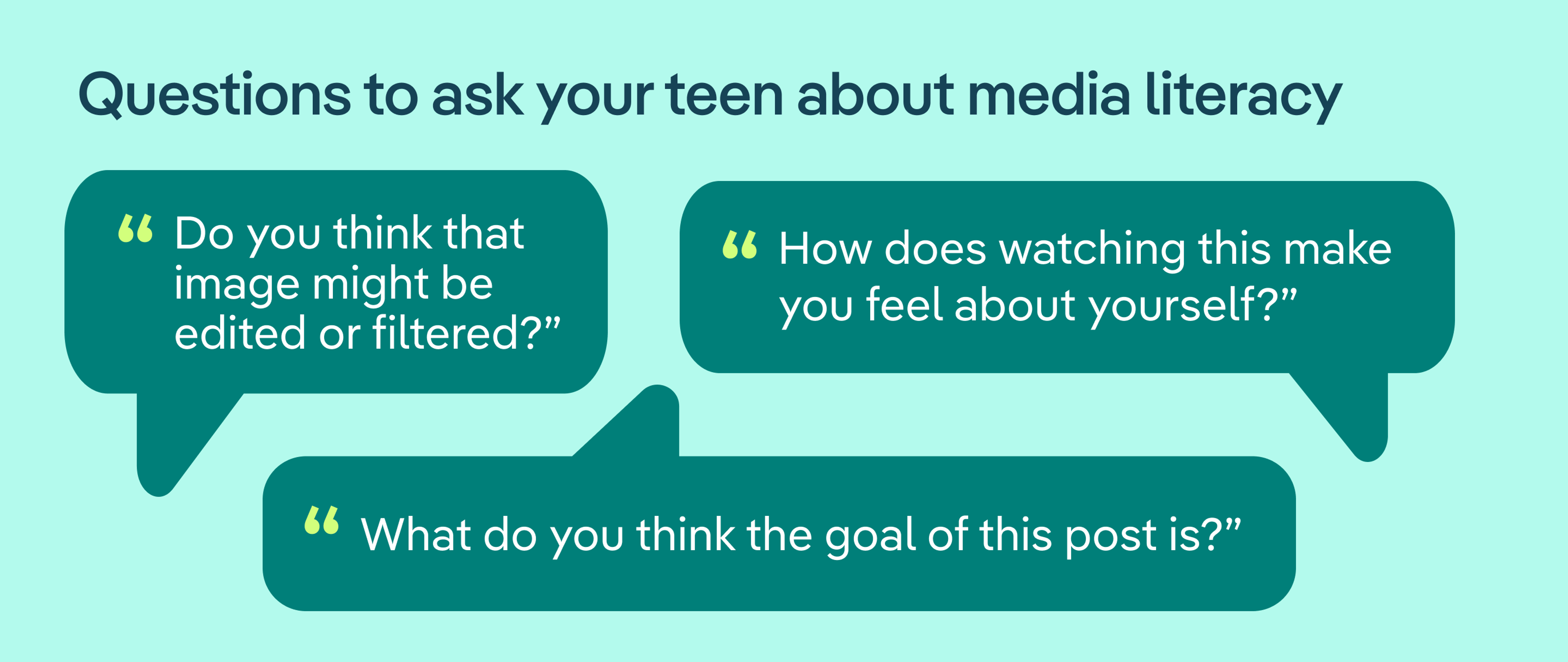

Lindenfeld recommends guiding—not restricting—your child’s digital world. Talk openly about how social media works, scroll their feed together, and ask gentle, curious questions, such as:

- “Do you think that image might be edited or filtered?”

- “What do you think the goal of this post is?”

- “How does watching this make you feel about yourself?”

When kids learn to pause and reflect on what they’re seeing, it gives them space to decide what values they want to absorb instead of letting algorithms choose for them.

Curate their feeds intentionally

Going through feeds together can be surprisingly powerful. Encourage teens to unfollow or mute accounts that promote extreme dieting, body shaming, or comparison and replace them with creators who celebrate body diversity, recovery, creativity, and real-life interests unrelated to appearance.

Remind your child that algorithms follow engagement. What they watch, like, and linger on shapes what they see next, so choosing healthier content can slowly change the tone of their feed.

Use parental controls and other tools that reduce exposure

Most platforms offer tools that can limit certain topics, block harmful keywords or hashtags, set daily screen time boundaries, and monitor who kids interact with.

While these tools aren’t perfect, they can offer important guardrails—particularly for younger children—and reduce exposure to explicit pro-eating disorder content on social media.

Reduce overall screen time

Less scrolling means less exposure to appearance-focused messaging. Set tech-free zones or times in your household (like during meals, family activities, or before bed) to create natural breaks from constant online input.

Encourage offline interests that build identity and joy outside of screens, such as art, sports, volunteering, music, or simply spending time with friends in person.

Create a supportive home environment

What kids hear at home matters. Avoid diet talk, weight commentary, or labeling foods as “good” or “bad.” Model balanced eating and positive body respect, including toward your own body, says Lindenfeld.

Check in regularly with curiosity, not criticism

Your tone is as important as your message. Instead of confrontational questions like “Why are you watching that?” try gentle check-ins:

- “What kind of stuff has been showing up on your feed lately?”

- “Is anything online making you feel stressed or weird?”

- “Do you ever compare yourself to what you see?”

The goal isn’t to open up a conversation. When kids feel safe being honest, they’re far more likely to share concerns before those concerns deepen into harmful patterns.

When and how to seek support

It’s easy to worry about overreacting, but you don’t need to wait for a crisis to ask for help. If concerns about social media start to overlap with ongoing changes in eating, weight, mood, or daily functioning, it’s time to consider professional support.

According to Lindenfeld, it’s time to reach out if you notice:

- Food restriction, bingeing, purging, or compulsive exercise

- Rapid or unexplained weight changes

- Intense fear of eating or weight gain

- Increasing secrecy, social withdrawal, or mood changes

- Growing fixation on body image or diet content online

- Missed periods

- Fainting or dizziness

Early support is linked to better outcomes, and getting help sooner can prevent symptoms from worsening.

Look for providers or programs that specialize in treating eating disorders in kids and teens and use a team approach (including medical, therapy, and nutritional care). When reaching out, you can ask:

- Do you specialize in adolescent eating disorders?

- How involved are families in treatment?

- How do you coordinate care across specialties?

Most importantly: You are not alone, and this is not your fault. Eating disorders are complex medical conditions, not parenting failures. Getting support is a powerful step toward recovery.

Not sure where to start? Equip offers a free eating disorder screener to help guide next steps and admissions specialists who can talk through options with your family.

The bottom line

Social media can powerfully influence how kids see their bodies and their worth, but parents are far from powerless. Understanding how online content shapes comparison, recognizing early warning signs, and having open, compassionate conversations can make a real difference. Eating disorders are serious, but they are also highly treatable, and recovery is possible with the right support. If something doesn’t feel quite right with your child, trusting your instincts and seeking help sooner rather than later can protect their health and set them on a path toward healing.

FAQ

How is social media affecting eating disorders?

Social media increases eating disorder risk by fueling constant body comparison, normalizing diet culture trends, and exposing kids to restrictive or appearance-focused content. Algorithms often intensify this exposure by serving progressively more extreme posts related to weight loss or food control, even when they don’t seek it out.

Does social media cause eating disorders?

Social media doesn’t cause eating disorders on its own. Eating disorders develop from a mix of genetic, emotional, and environmental factors. However, social media can significantly increase risk by amplifying appearance pressure, diet messaging, and comparison that can trigger or worsen symptoms.

What role does media play in the development of eating disorders?

Media helps shape body image by promoting narrow beauty standards and linking thinness to worth or success. On social platforms, algorithms magnify these messages, making harmful content more common and harder to avoid. While media isn’t the sole cause, it contributes to an environment that raises eating disorder risk.

Alberga, Angela S et al. “Fitspiration and thinspiration: a comparison across three social networking sites.” Journal of eating disorders vol. 6 39. 26 Nov. 2018, doi:10.1186/s40337-018-0227-x

Aparicio-Martinez, Pilar et al. “Social Media, Thin-Ideal, Body Dissatisfaction and Disordered Eating Attitudes: An Exploratory Analysis.” International journal of environmental research and public health vol. 16,21 4177. 29 Oct. 2019, doi:10.3390/ijerph16214177

Capuano, Elena Ilaria et al. “Gender differences in eating disorders.” Frontiers in nutrition vol. 12 1583672. 2 Jun. 2025, doi:10.3389/fnut.2025.1583672

Chaikali, Panagiota et al. “Body Composition, Eating Habits, and Disordered Eating Behaviors among Adolescent Classical Ballet Dancers and Controls.” Children (Basel, Switzerland) vol. 10,2 379. 15 Feb. 2023, doi:10.3390/children10020379

Dane, Alexandra, and Komal Bhatia. “The social media diet: A scoping review to investigate the association between social media, body image and eating disorders amongst young people.” PLOS global public health vol. 3,3 e0001091. 22 Mar. 2023, doi:10.1371/journal.pgph.0001091

Kaiser CK, Edwards Z, Austin EW. Media Literacy Practices to Prevent Obesity and Eating Disorders in Youth. Curr Obes Rep. 2024 Mar;13(1):186-194. doi: 10.1007/s13679-023-00547-8. Epub 2024 Jan 6. PMID: 38183580.

Meneguzzo, Paolo et al. “Bridging trauma and eating disorders: the role of loneliness.” Frontiers in psychiatry vol. 15 1500740. 10 Dec. 2024, doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1500740

Nagata, Jason M et al. “Emerging trends in eating disorders among sexual and gender minorities.” Current opinion in psychiatry vol. 33,6 (2020): 562-567. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000645

National Institute of Mental Health. “Eating Disorders: What You Need to Know.” National Institute of Mental Health, 2024, www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/eating-disorders.

Norton, Bethany et al. “Overlap of eating disorders and neurodivergence: the role of inhibitory control.” BMC psychiatry vol. 24,1 454. 18 Jun. 2024, doi:10.1186/s12888-024-05837-6

Suárez, Rosario et al. “Effects of health at every size based interventions on health-related outcomes and body mass, in a short and a long term.” Frontiers in nutrition vol. 11 1482854. 8 Oct. 2024, doi:10.3389/fnut.2024.1482854

Sukunesan, Suku et al. “Examining the Pro-Eating Disorders Community on Twitter Via the Hashtag #proana: Statistical Modeling Approach.” JMIR mental health vol. 8,7 e24340. 9 Jul. 2021, doi:10.2196/24340

Tan, Juliet Sher Kit et al. “Eating disorders in children and adolescents.” Singapore medical journal vol. 63,6 (2022): 294-298. doi:10.11622/smedj.2022078