- Binge eating disorder (BED) is the most common eating disorder. It’s a complex mental health condition rooted in emotional, behavioral, and biological factors.

- BED can affect people of any size, age, and background, and often flies under the radar because it doesn’t match stereotypes of eating disorders.

- Common characteristics include loss of control, secrecy, food “noise,” shame cycles, and restriction-binge loops.

- Evidence-based treatment works, and can help people struggling with BED quiet their thoughts about food and restore trust.

If you’ve ever thought, “I can’t stop eating—what’s wrong with me?” you’re likely carrying a lot of confusion and frustration about food. For many people, binge eating disorder (BED) involves eating past comfort, feeling out of control around certain foods, or hiding how much they ate, followed by heavy feelings like guilt, embarrassment, or shame.

Over time, this can turn into a draining cycle. You promise tomorrow will be different, blame stress or emotions, or try another diet, only to feel discouraged when nothing changes.

Despite what pervasive diet culture and the weight loss industry may lead people to believe, binge eating disorder is a real mental health condition, not a failure of willpower. It often involves intense urges to binge, feeling unable to stop once you start, and emotional distress before or after eating. And it can affect people of any body size, age, gender, or background.

Here, we’ll explain what BED is, what it looks like, and how to get the right support, whether you’re seeking answers for yourself or someone you care about.

What is binge eating disorder (BED)?

The definition of binge eating disorder is “repeatedly eating unusually large amounts of food in a short period of time, accompanied by a sense of loss of control,” says Jen Simmons, PhDc, LPC, therapy lead at Equip. “During a binge, a person may feel unable to stop eating, may disconnect or dissociate, may eat much faster than normal, and often continues eating even after becoming uncomfortably full.”

According to the DSM-5-TR, a binge has two key parts:

- Eating an objectively large amount of food in a discrete period (usually within two hours)

- Feeling unable to stop or control what or how much you’re eating.

To meet the criteria for BED, these episodes happen at least once a week for three months, cause significant distress, include several common features (like eating rapidly or eating when not hungry), and occur without regular purging or other compensatory behaviors.

This is different from everyday overeating or emotional eating. Most people occasionally eat more than they meant to or turn to food for comfort during stressful moments, according to Sharon Batista, MD, assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at Mount Sinai Hospital. With BED, the pattern is more compulsive and distressing.

BED is also very common: about 1 to 3 percent of adults in the U.S. experience it at some point, making it the most common eating disorder (for comparison, anorexia nervosa affects an estimated 0.6 percent of adults). Still, it often goes unrecognized or untreated.

Diet culture plays a big role in that. Many people are taught that struggling with food means they lack discipline or willpower, and that stricter diets or exercise plans should fix it. So when binge eating continues despite those efforts, people tend to blame themselves.

But ironically, restriction can actually make binge eating more likely. Over time, deprivation raises cravings and thoughts about food, making binge urges stronger. That can lead to the familiar cycle of restricting, bingeing, feeling ashamed, then trying to restrict again.

If you’re experiencing BED, know that it isn’t a sign of weakness. It’s a pattern shaped by stress, emotions, brain chemistry, deprivation, and shame—patterns that are treatable with the right support.

What are signs and symptoms of binge eating disorder?

“People with binge eating disorder often experience a painful and complex internal world marked by shame, guilt, disgust, anxiety, and depression,” says Simmons. “These emotions are frequently connected to fears of gaining weight or deep dissatisfaction with their body image.”

Here’s a breakdown of the most common signs.

Behavioral signs

According to Simmons and Batista, behavioral signs of BED include:

- Recurrent binge episodes that involve compulsive overeating

- Eating in secret

- Eating very quickly

- Eating past discomfort

- Planned binges or rituals around binges

- Skipping meals or “starting over” (like restricting food as soon as a binge ends)

- Avoiding food-centered situations

Psychological signs

Keeping the behaviors associated with binge eating disorder a secret can create a profound sense of isolation. And “as isolation grows, so does the emotional distress that often triggers another binge, creating a cycle that becomes increasingly difficult to break,” says Simmons.

According to both experts, other emotional and psychological symptoms may include:

- Loss of control around food

- Food “noise” (aka constant mental chatter about eating)

- Shame, guilt, or harsh self-talk

- Anxiety or depression

- All-or-nothing thinking (like labeling foods or days as “good” or “bad”)

- Fear of judgment

Physical signs

The body often reflects the binge-restrict cycle too, even if these symptoms are easy to overlook or dismiss as “just digestion issues” or “stress.” Physical symptoms can include:

- Painful fullness or bloating

- Digestive issues

- Fatigue or energy swings

- Symptoms linked to irregular blood sugar levels, like shakiness, lightheadedness, irritability, or brain fog

- Weight fluctuations

Beyond day-to-day physical symptoms, binge eating disorder is also associated with several longer-term medical conditions. Some people develop blood sugar dysregulation or type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, elevated cholesterol, sleep apnea, or cardiovascular strain over time.

These complications aren’t inevitable, but they do highlight why BED deserves medical care and support, not self-blame or “toughing it out.”

What does binge eating disorder feel like?

For people living with BED, the hardest part is often what’s happening on the inside.

“Many individuals feel embarrassed about their relationship with food, avoiding meals with others and hiding binges in private because they fear being judged,” says Simmons. “The cycle of isolation, bingeing, and self-criticism feeds on itself, making recovery seem even further out of reach.”

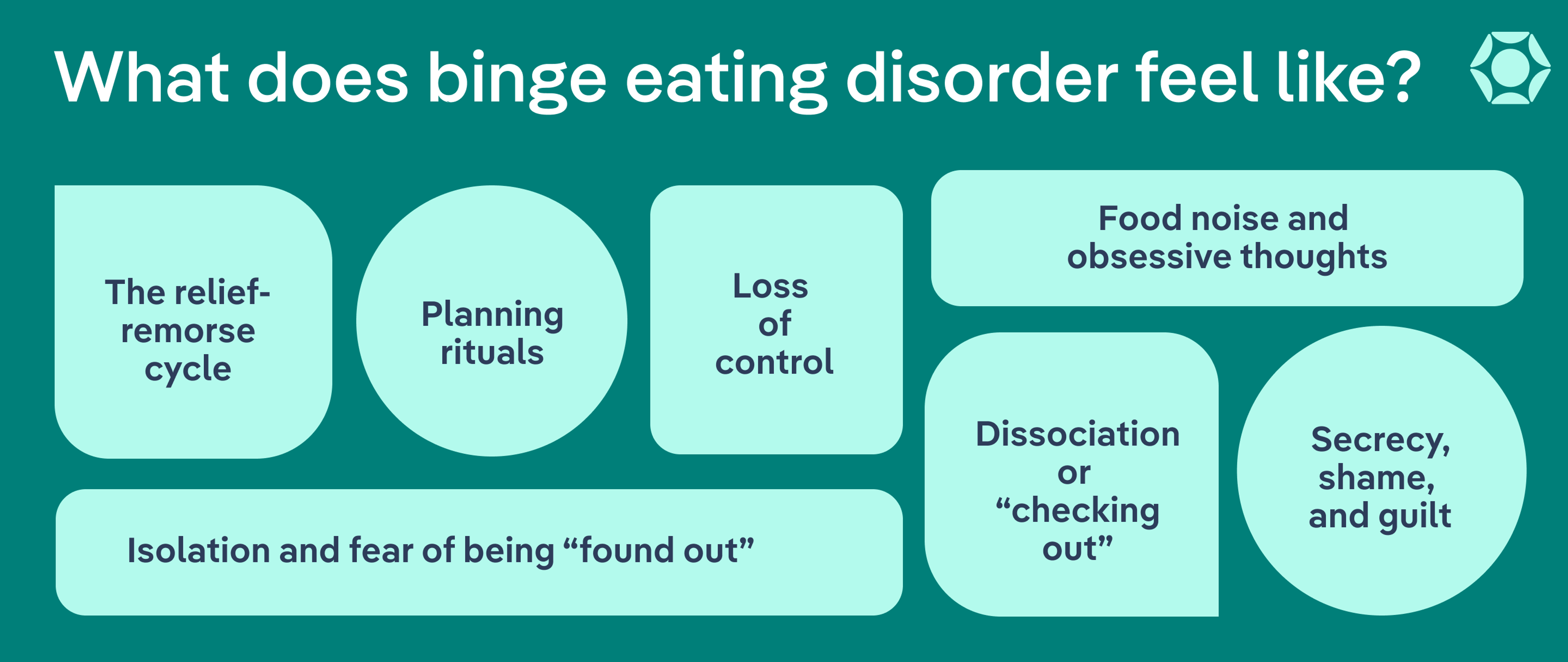

According to Simmons and Batista, people with BED often describe a constellation of internal experiences that repeat over time, including:

- Food noise and obsessive thoughts: Food can start to take up so much mental space that it becomes hard to focus on anything else.

- Loss of control: Once a binge begins, it often feels impossible to slow down or stop, even when you want to.

- Dissociation or “checking out”: Many people report mentally disconnecting during binges, feeling numb, zoned out, or detached.

- Secrecy, shame, and guilt: People may go to great lengths to conceal food, clean up evidence of binges, or lie about their compulsive eating.

- Planning rituals: Binges may become highly planned, with specific foods, routines, or “rules” around when and how they happen.

- The relief-remorse cycle: Many people experience brief emotional relief in the middle of a binge—a numbing of stress, sadness, or anxiety—followed by a heavy crash of guilt, shame, or fear once it’s over.

- Isolation and fear of being “found out”: Worry about others noticing eating patterns or body changes can lead to social withdrawal and eating alone.

All of these experiences can exist at the same time, and none of them mean you’re broken or weak. They reflect how the nervous system, emotions, and brain are trying to cope with distress. With the right support and treatment, this internal landscape can grow smoother, more nourishing, and less overwhelming over time.

What causes binge eating disorder?

There’s no single cause of binge eating disorder. Instead, it’s often triggered by a combination of biological, emotional, and environmental factors.

Biological factors

Some people are more biologically vulnerable to developing BED based on how their brains and bodies respond to food and stress. A few of the most common biological risk factors include:

- Genetic predisposition: Having family members with eating disorders, mood disorders, ADHD, or substance use disorders increases risk.

- Brain chemistry, reward pathways, and neurodivergence: For some people — especially those with ADHD or other neurodivergent traits — dopamine systems (which regulate mood, reward, and impulse control) may become tightly linked to eating for comfort or relief. That means food can trigger deeply rewarding experiences, which may reinforce binge patterns over time.

- Effects of restriction: Skipping meals or under-eating can intensify cravings, making binge urges stronger and harder to resist.

Psychological factors

For many people, binge eating becomes a way to cope with emotions that feel overwhelming, unmanageable, or hard to put into words. Common psychological factors include:

- Emotional regulation challenges: Food may temporarily soothe anxiety, sadness, anger, loneliness, or emotional overload when other coping tools feel unavailable.

- Trauma or chronic stress: Past trauma, ongoing caregiving stress, financial strain, or high work pressure can dysregulate the nervous system and make bingeing more likely as a numbing or self-soothing response.

- Perfectionism and shame: All-or-nothing thinking (“I messed up, might as well binge”) and intense self-criticism feed both restriction and bingeing.

- Avoidance patterns: Binge eating can offer escape from uncomfortable feelings or situations, even if that relief is short-lived.

Environmental and cultural factors

The world we live in can fuel BED, even when people are trying hard to “do everything right.” Contributing factors can include:

- Restriction: Skipping meals, cutting out foods, following rigid food rules, or trying to “make up for” eating can push the body into intense hunger and increase mental preoccupation with food. This physical and emotional deprivation is one of the strongest triggers for binge urges.

- Diet culture: Messages about “good” and “bad” foods, ideal body sizes, or the belief that thinner is “better” or more attractive can reinforce shame, drive restrictive eating, and deepen the binge–restrict cycle.

- Weight stigma: Experiencing judgment or pressure around body size can intensify shame, secrecy, and emotional distress.

- Disrupted routines: Long workdays, inconsistent meals, or chaotic schedules can push the body into intense hunger states that lower emotional resilience.

Co-occurring conditions

BED often overlaps with other mental health conditions that affect emotional regulation, impulse control, or stress response, including:

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Anxiety disorders

- Depression

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or trauma-related conditions

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

These conditions don’t cause BED on their own, but they can make binge urges stronger and recovery more complex without targeted support.

What are the long-term health risks of binge eating disorder?

BED can slowly wear down both emotional and physical well-being, making everyday life feel smaller, harder, and less fulfilling. Without support, BED can gradually impact mental health, physical well-being, and daily functioning in many key ways.

Mental and emotional health effects

- Worsening anxiety or depression

- Increased shame and self-criticism

- Social withdrawal

- Increased secrecy or avoidance

- Emotional dysregulation

- Difficulty with routines or concentration

- Heightened impulsivity around food

Physical health effects

Interestingly, although people may believe that some of these physical health effects of BED are due to weight gain that comes from binge eating, such as blood sugar problems (including Type II diabetes), these problems are actually related to the binge eating rather than weight. It's estimated that 30% of people with BED are in a "normal" BMI range, and they have these issues too.

- Digestive problems (including reflux, bloating, constipation, nausea, or chronic stomach discomfort)

- Sleep disruption and fatigue

- Blood sugar irregularities

- Cardiovascular strain

What’s the difference between binge eating disorder, bulimia, emotional overeating, and stress eating?

These experiences are often lumped together because they all involve eating past hunger or eating in response to emotions. But there are key differences in the behaviors, related emotions, and what happens after eating.

Binge Eating Disorder vs. Emotional Eating vs. Stress Eating vs. Overeating

| Feature | Binge Eating Disorder (BED) | Emotional/ Stress Eating | Overeating |

| Binge episodes | Yes — repeated episodes involving large amounts of food | No true binge episodes | No |

| Loss of control while eating | Yes | Sometimes | Usually no |

| Purging or compensatory behaviors | Rarely | Rarely | Rarely |

| Emotional distress afterward | High | Mild to moderate | Usually low or none |

| Frequency & pattern | At least weekly for 3+ months | Occasional or situational | Occasional; often tied to events (e.g., holidays) |

| Primary driver | Compulsion + loss of control | Coping with emotions/stress | Enjoyment, habit, cultural norms |

| Impact on daily life | Often significant | Mild to moderate | Minimal |

| Needs clinical treatment | Yes | Not always | No |

Binge eating disorder vs. overeating

Everyone overeats occasionally, like at holidays, celebrations, or during especially busy or stressful days. What separates overeating from BED is pattern and distress, says Simmons.

With BED, binges happen repeatedly and are associated with a loss of control and emotional distress afterwards. Overeating, on the other hand, is occasional, more controllable, and not linked to intense guilt.

Binge eating disorder vs. emotional/stress eating

Emotional and stress eating involve using food to cope with feelings or stress, according to Simmons. That could look like rewarding yourself after a hard day, eating to cope with stress or sadness, or reaching for food during difficult life events, she explains.

However, emotional eating is occasional and not associated with the same levels of distress or everyday disturbances as BED, adds Batista.

Binge eating disorder vs. bulimia

Both BED and bulimia include binge episodes. The key difference is what happens afterward.

“Binge eating disorder (BED) involves repeatedly eating unusually large amounts of food in a short period of time, [but] there are no regular purging behaviors,” says Simmons. “Bulimia nervosa also includes episodes of binge eating, but it is followed by … vomiting, laxative or diuretic use, excessive exercise, or any behavior aimed at getting rid of food or preventing weight gain.”

How is binge eating disorder diagnosed?

Binge eating disorder is diagnosed using standardized clinical guidelines from the DSM-5-TR, the manual mental health professionals use to identify and treat eating disorders.

Rather than focusing on body size or appearance, diagnosis looks at patterns of behavior and emotional distress. According to Batista, a medical or mental health professional will check for:

- Recurrent binge episodes that include eating rapidly, eating until physically uncomfortable, eating when not hungry, eating alone due to embarrassment, or feeling guilt or disgust afterward

- Ongoing distress and loss of control

- Binges occurring at least once a week for three months

- No regular purging

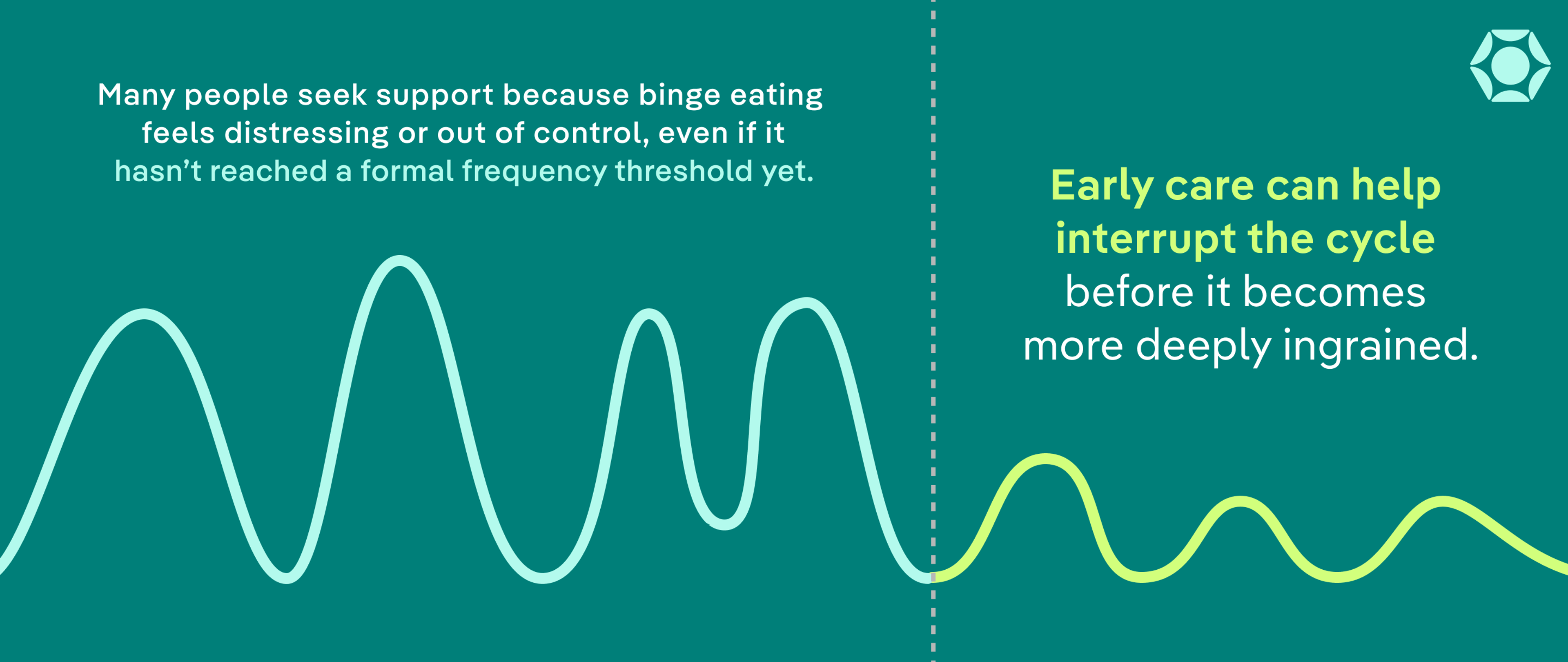

It’s also important to know that you don’t have to meet every diagnostic criterion to benefit from binge eating disorder treatment. Many people seek support because binge eating feels distressing or out of control, even if it hasn’t reached the formal frequency threshold yet. Early care can help interrupt the cycle before it becomes more deeply ingrained.

Finally, it’s important to understand that BED can occur at any body size. Weight is not part of the diagnostic criteria, and how someone looks has no bearing on whether their eating struggles are real or deserving of care.

What does binge eating disorder treatment look like?

There isn’t a single “one-size-fits-all” solution for binge eating disorder treatment. Here’s a look at the core evidence-based approaches commonly used in treatment for binge eating disorder and why they help, according to Simmons and Batista.

First line therapies:

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and enhanced CBT (CBT-E): CBT identifies thoughts and behaviors that drive binge cycles and teaches practical skills to regulate eating, challenge shame-based thinking, and interrupt habitual patterns. CBT-E is a specialized version designed specifically for eating disorders.

- Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT): This treatment addresses relationship stress, grief, life transitions, or social conflicts that may trigger binge eating and reinforce isolation.

Supplemental therapies:

These are typically integrated alongside the above modalities.

- Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT): This type of therapy focuses on learning skills for emotional regulation, distress tolerance, and impulsivity—key building blocks for managing binge urges when emotions feel overwhelming.

- Integrative cognitive-affective therapy (ICAT): This therapy combines emotional processing with behavior change, helping people recognize emotional triggers in the moment and respond with healthier coping strategies.

- Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT): In this type of therapy, you learn skills to tolerate uncomfortable thoughts or urges without acting on them, while strengthening your connection to personal values and long-term goals.

- Family-based treatment (FBT): When BED occurs in young people, FBT can be an effective approach.

- Treatment for co-occurring conditions: Addressing related challenges like ADHD, anxiety, depression, trauma, or sleep disorders can make binge urges easier to manage and support long-term stability.

Other treatment methods:

- Medications: Vyvanse is FDA-approved for adults with BED. Other medications, such as SSRIs or treatments for ADHD, anxiety, or depression, can support recovery when co-occurring conditions are present.

- Nutrition therapy (non-diet, non-restrictive): Registered dietitians help patients establish consistent, nourishing meal patterns and remove rigid food rules. Regular eating reduces physical deprivation and steadies hunger signals, which lowers vulnerability to binges.

- Mentorship and lived-experience support: Peer mentors offer encouragement, normalization, and practical guidance from someone who has walked the recovery path themselves. Feeling understood can reduce shame and isolation.

What does binge eating disorder recovery look like?

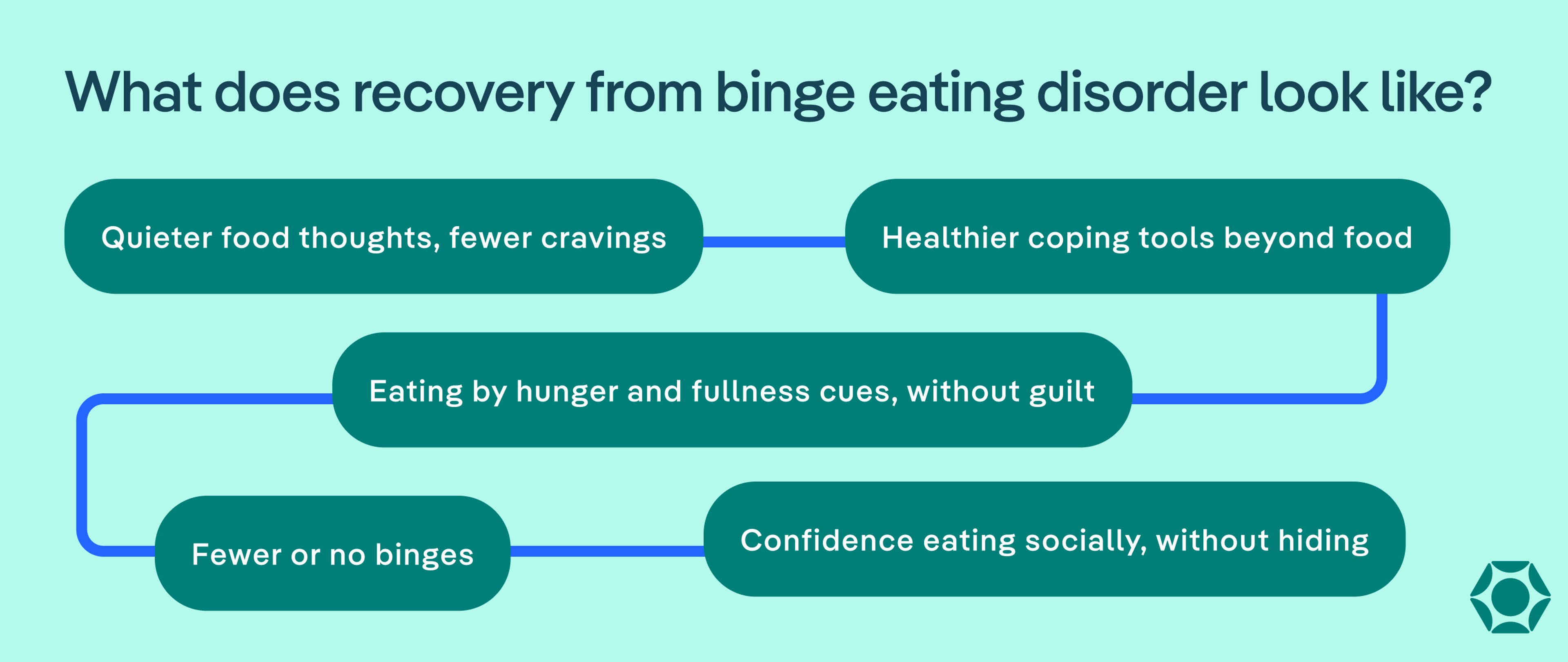

“Recovery from BED is a process, not a single event,” says Batista. “Clinically, recovery means a significant reduction or cessation of binge episodes, improved emotional regulation, and a healthier relationship with food and one’s body.”

In treatment, recovery often begins with something that can feel counterintuitive: learning to eat regular, consistent meals and snacks to normalize eating patterns. This steady nourishment helps interrupt the binge-restrict cycle, says Simmons: When the body is fed consistently, urges begin to soften, and binges naturally decrease over time.

As you start to settle into recovery, Batista says many people begin to notice small but meaningful shifts, such as:

- Quieter food thoughts and fewer intrusive cravings

- Eating when hungry and stopping when comfortably full without fear or guilt

- Fewer or no binges

- Turning to emotional regulation tools instead of food when stress or big feelings arise

- Feeling more comfortable eating socially and re-engaging in daily life without secrecy

Recovery is often described through everyday wins, like keeping all foods in the home without anxiety or no longer planning entire days around potential binges.

“It’s important to note that recovery does not always mean weight loss,” adds Batista. “The focus is on reducing binge behaviors and distress, not on achieving a specific weight.”

When and how to reach out for help

You don’t need to “hit rock bottom” to deserve help for binge eating disorder. If food, weight, or eating behaviors are taking up a lot of mental space, that’s reason enough to talk to someone.

According to Simmons and Batista, it may be time to reach out for help if you find yourself:

- Binging regularly (even if it doesn’t feel “often enough” to count)

- Feeling out of control around food or stuck in cycles of bingeing and restricting

- Thinking about food, eating, or weight most of the day

- Eating in secret or feeling intense shame after binge eating

- Using food to cope with emotions

- Avoiding social situations because of eating-related anxiety

Getting support can start small. You might begin by talking with your primary care provider, a therapist, or a registered dietitian who specializes in eating disorders. If you’re unsure whether what you’re experiencing qualifies as an eating disorder, this quick screening tool can help clarify your next steps.

“Most importantly, eating disorders are never your fault,” says Simmons. “You didn’t cause them, and you’re not doing anything wrong by struggling. They are real mental health conditions that deserve care, compassion, and effective treatment. With the right support, full recovery is absolutely possible.”

Conclusion

Binge eating disorder is a real, treatable mental health condition, not a failure of discipline or willpower. With evidence-based care, including regular eating, therapy, and emotional support, you can break the binge-restrict cycle. Food thoughts soften, you’ll rebuild trust in your body, and daily life begins to feel steadier again. If any of this resonates with you, support is available, and reaching out can be the first meaningful step toward recovery.

FAQ

What happens to your body when you binge eat?

When you binge eat, you often eat very quickly and past the point of comfort, which can cause bloating, stomach pain, nausea, fatigue, and reflux. Blood sugar can spike and crash, leading to feeling shaky, foggy, or irritable afterward. Emotionally, many people feel ashamed or upset, which adds stress and keeps the binge cycle going.

How common is binge eating disorder?

Binge eating disorder is the most common eating disorder. About 1 to 3 percent of adults in the U.S. experience it at some point. It affects people of all genders, ages, and body sizes, and many struggle for years before realizing what they’re dealing with or getting support.

Why can’t I stop binge eating?

Binge urges are driven by the body and brain, not a lack of discipline. Dieting or skipping meals makes hunger and cravings stronger, and stress or emotions can make food feel like a quick relief. Over time, your brain learns to rely on bingeing to cope, which is part of what makes it hard to stop binge eating. That’s why treatment focuses on eating regularly and building emotional coping skills, not trying harder to control food.

- “APA - Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition Text Revision DSM-5-TR.” Appi.org, 2022, www.appi.org/Diagnostic_and_Statistical_Manual_of_Mental_Disorders_Fifth_Edition_Text_Revision_DSM-5-TR.

- Bray, Brenna et al. “Binge Eating Disorder Is a Social Justice Issue: A Cross-Sectional Mixed-Methods Study of Binge Eating Disorder Experts' Opinions.” International journal of environmental research and public health vol. 19,10 6243. 20 May. 2022, doi:10.3390/ijerph19106243

- Bray, Brenna et al. “Mental health aspects of binge eating disorder: A cross-sectional mixed-methods study of binge eating disorder experts' perspectives.” Frontiers in psychiatry vol. 13 953203. 15 Sep. 2022, doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.953203

- Casari, Matheus Augusto et al. “Does Restriction Lead to Binge Eating? A Scoping Review on Restrictive Diets in the Development and Maintenance of Binge Eating Disorder.” Nutrition reviews, nuaf163. 23 Aug. 2025, doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuaf163

- Dingemans, Alexandra et al. “Emotion Regulation in Binge Eating Disorder: A Review.” Nutrients vol. 9,11 1274. 22 Nov. 2017, doi:10.3390/nu9111274

- Habib, Ashna, et al. “Unintended Consequences of Dieting: How Restrictive Eating Habits Can Harm Your Health.” International Journal of Surgery Open, vol. 60, no. 100703, 1 Nov. 2023, p. 100703, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S240585722300116X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijso.2023.100703.

- Hollett, Kayla B, and Jacqueline C Carter. “Separating binge-eating disorder stigma and weight stigma: A vignette study.” The International journal of eating disorders vol. 54,5 (2021): 755-763. doi:10.1002/eat.23473

- Iqbal, Aqsa, and Anis Rehman. “Binge Eating Disorder.” PubMed, StatPearls Publishing, 2022, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551700/.

- John Hopkins Medicine. “Binge Eating Disorder.” Johns Hopkins Medicine, 2019, www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/eating-disorders/binge-eating-disorder.

- Leenaerts, Nicolas et al. “The neurobiological reward system and binge eating: A critical systematic review of neuroimaging studies.” The International journal of eating disorders vol. 55,11 (2022): 1421-1458. doi:10.1002/eat.23776

- Mills, Regan et al. “Early intervention for eating disorders.” Current opinion in psychiatry vol. 37,6 (2024): 397-403. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000963

- Monteleone, Alessio Maria et al. “COVID-19 Pandemic and Eating Disorders: What Can We Learn About Psychopathology and Treatment? A Systematic Review.” Current psychiatry reports vol. 23,12 83. 21 Oct. 2021, doi:10.1007/s11920-021-01294-0

- NIDDK. “Definition & Facts for Binge Eating Disorder.” National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 22 Mar. 2019, www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/weight-management/binge-eating-disorder/definition-facts.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. “Symptoms & Causes of Binge Eating Disorder | NIDDK.” National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, May 2021, www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/weight-management/binge-eating-disorder/symptoms-causes.

- National Institute of Mental Health. “Eating Disorders.” www.nimh.nih.gov, National Institute of Mental Health, Nov. 2017, www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/eating-disorders.