- Eating disorders can affect anyone, no matter their body size, gender, or background.

- Emotional and behavioral warning signs often appear long before any physical changes.

- Early intervention leads to better outcomes, but many signs are easy to miss or misinterpret.

- Paying attention to shifts in mood, habits, and flexibility around food can help catch concerns early.

- Professional support is essential—no one should have to navigate recovery alone.

When a friend insists they’ve just “gotten healthy,” starts skipping group dinners, or cuts out entire food groups overnight, it can be hard to know what’s normal and what’s cause for concern. Early signs of an eating disorder often look like “healthy habits”—especially in a culture that praises restriction, discipline, and “clean eating.”

I know that firsthand. When I developed an eating disorder as a teenager (anorexia nervosa), it was easy to pass my behaviors off as self-control. I told myself I was being mindful, long before any physical changes appeared.

But eating disorders aren’t lifestyle choices. They’re serious, complex mental health conditions. Common types of eating disorders include:

- Anorexia nervosa: Restriction and fear of weight gain. Note that there are two types of AN, anorexia nervosa, restricting type (ANR), and anorexia nervosa, binge/purge type (AN b/p). Both types involve restriction, leading to a significantly low body weight, and fear of weight gain, but b/p type will also engage in regular episodes of purging and sometimes even binging. The hallmark of both types of AN having is a dangerously low body weight and fear of weight gain.

- Bulimia nervosa: Cycles of bingeing and compensatory behaviors like purging or excessive exercise

- Binge-eating disorder (BED): Recurrent binges accompanied by loss of control and distress

- Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID): Food avoidance due to sensory sensitivities, fear of negative outcomes, or lack of interest/low appetite, not body image concerns

- Other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED): Disordered patterns that cause severe distress but don’t fit neatly into the other categories. These can be just as dangerous.

In this guide, we’ll break down the most common eating disorder symptoms, how they can look different from person to person, and what to do if you notice these signs in yourself or a loved one.

What are signs of an eating disorder?

While every eating disorder looks a little different, many warning signs overlap, says Heather Rosen, PhD, director of the Eating Disorders Program at Psychology Partners Group.

Because these signs often develop gradually—and can look like “healthy choices”—they’re easy to miss. Eating disorders also thrive in secrecy, with many behaviors happening in private, adds Rosen.

Below are some of the most common physical, behavioral, and emotional signs of an eating disorder. These can appear across conditions like anorexia, bulimia, binge-eating disorder, ARFID, and OSFED.

Physical signs

Eating disorders affect the body in many ways, and those changes aren’t always obvious. You can’t tell if someone has an eating disorder just by looking at them—research shows less than 6% of people with eating disorders are medically underweight.

According to Rosen and Melodie Simmons, DHA, LPC, CEDS-C, a clinical instructor at Equip, you might notice:

- Noticeable weight or growth changes

- Fatigue, dizziness, or weakness

- Feeling cold all the time

- Dry skin, brittle nails, or hair thinning

- Missed or irregular periods

- Stomach pain, bloating, or constipation

Behavioral signs

Changes in behavior often appear before any physical symptoms do. According to Rosen and Simmons, these signs can include:

- Avoiding meals with others or eating alone

- Strict food rules or rituals (cutting food into tiny pieces, eliminating food groups)

- Frequent moralizing of food (categorizing foods as “good” or “bad”)

- Overexercising or exercising when injured or sick

- Hiding or hoarding food

- Withdrawing from social activities involving food

Emotional and cognitive signs

These internal shifts can be easy to miss but are often the strongest indicators that something deeper is happening. According to the experts, signs may include:

- Anxiety, irritability, or depression

- Guilt or shame after eating

- Perfectionism or rigid thinking

- Distorted body image

- Denial or defensiveness about eating behaviors

What are signs of anorexia nervosa?

Anorexia is marked by restrictive eating and an intense fear of weight gain, but the emotional and behavioral signs usually appear long before any physical changes. “Anorexia often starts with subtle shifts families might initially interpret as healthy habits,” says Simmons. “All of these behaviors are not choices—the eating disorder has taken over.”

Here’s the breakdown of signs to look for.

Physical signs

Physical changes vary widely and aren’t always visible. Some people with anorexia aren’t underweight, and weight alone isn’t part of the diagnosis. In fact, people with atypical anorexia nervosa (AAN)—individuals living in larger bodies who become preoccupied with losing weight and yet remain or end up in a range typically considered “healthy”— experience nearly all the same symptoms but maintain a “normal” or higher weight.

According to Simmons and Rosen, you may notice signs such as:

- Rapid or unexplained weight loss, or slowed growth in children and teens

- Fatigue, dizziness, or fainting from low blood pressure or inadequate nutrition

- Feeling cold all the time due to reduced metabolism

- Brittle hair, nails, or dry skin from nutrient deficiencies

- Missing or irregular menstrual cycles caused by hormonal imbalance

- Slow heart rate or low blood pressure as the body conserves energy

- Appearance of fine body hair or lanugo

Behavioral signs

Many behavioral signs happen in private or get mistaken for admirable “discipline.” In a culture deeply influenced by diet culture—which often praises restriction, willpower, and shrinking one’s body—these patterns can be overlooked or even encouraged. That can make it harder for people to get help early, even as the eating disorder begins to take priority over relationships, school, or work.

Per the experts, symptoms can include:

- Cutting out entire food groups or drastically shrinking portion sizes

- Claiming to have eaten already

- Pushing food around the plate

- Exercising excessively, even when ill or injured

- Restlessness or anxiety around meals; leaving early or avoiding shared eating

- Frequent weighing or body checking

- Losing interest in hobbies or socializing as diet and exercise take over

Emotional and cognitive signs

Anorexia often heightens perfectionism and emotional distress, creating a cycle of guilt and control. Simmons and Rosen say this can look like:

- Intense fear of weight gain or “losing control”

- Irritability or withdrawal

- Black-and-white thinking around food (“good” vs. “bad” foods)

- Preoccupation with body image or perceived flaws

- Denial about the seriousness of symptoms or need for help

- Increasing rigidity around food, where rules and routines around eating become inflexible

What are signs of bulimia nervosa?

Bulimia nervosa involves cycles of binge eating—consuming large amounts of food in a short time—followed by compensatory behaviors like vomiting, fasting, or overexercising.

“Bulimia often hides beneath normal eating and sometimes even normal weight, which can make early detection difficult,” says Simmons. Here’s what to look out for.

Physical signs

Physical effects usually stem from the binge-purge cycle, not from weight alone. According to Simmons and Rosen, you might notice:

- Puffy cheeks or jaw swelling from enlarged salivary glands (“bulimia jaw”)

- Dental enamel erosion or increased cavities from stomach acid

- Sore throat or hoarse voice due to repeated vomiting

- Scars or calluses on knuckles or hands (known as Russell’s sign)

- Frequent stomach pain, bloating, or digestive discomfort

- Fluctuating weight caused by alternating restriction and overeating

Behavioral signs

Bulimia thrives in secrecy, and many behaviors are mistaken for stress or digestive issues. Per the experts, common patterns include:

- Going to the bathroom immediately after meals

- Eating large amounts of food quickly or in secret; hiding wrappers or containers

- Using laxatives, diuretics, or diet pills to compensate for eating

- Exercising excessively after meals to “undo” food intake

- Skipping meals or fasting after binges

Emotional and cognitive signs

The emotional experience of bulimia often centers on shame, secrecy, and loss of control. Here’s what Simmons and Rosen say to look out for:

- Guilt or self-blame after eating

- Emotional highs and lows around meals

- Distorted body image and constant dissatisfaction with appearance

- Perfectionism and harsh self-criticism

- Defensiveness or secrecy when asked about eating habits

What are signs of binge-eating disorder?

Binge-eating disorder is the most common eating disorder in the U.S. It involves recurring episodes of eating unusually large amounts of food in a short period of time while feeling out of control during the episode. It’s then followed by distressing emotions such as guilt, shame, or frustration, but without purging or other compensatory behaviors.

“BED can appear as emotional or stress-related overeating, but with BED, the loss of control becomes distressing and repetitive,” says Simmons. “Oftentimes, people describe feeling ‘numb’ during a binge.” Here are the other signs to look out for.

Physical signs

BED doesn’t have a “look.” It can affect people in any body size. Physical symptoms are often related to inconsistent nourishment or digestive strain rather than weight alone. According to Simmons and Rosen, here’s what that can look like:

- Fluctuating weight due to cycles of overeating and restriction (known as the binge-restrict cycle)

- Frequent stomach pain, bloating, or digestive discomfort

- Fatigue or low energy from blood sugar spikes and crashes

- Sleep problems linked to nighttime eating episodes

Behavioral signs

Behavioral symptoms often revolve around secrecy, shame, and attempts to hide binge episodes, says Simmons. Signs can include:

- Eating large amounts of food quickly, even when not hungry

- Eating alone or in secret to avoid judgment

- Hoarding or hiding food in bedrooms, cars, or bags

- Frequent dieting or restricting after binges, which perpetuates the binge-restrict cycle

- Avoiding social events involving food due to embarrassment or anxiety

Emotional and cognitive signs

The emotional toll of BED often centers around guilt, shame, and a painful sense of loss of control, according to Simmons. This can look like:

- Guilt or embarrassment after eating

- Feeling “numb” or detached during binges

- Low self-esteem or negative body image

- Stress, boredom, or sadness triggering binge episodes

What are signs of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID)?

ARFID is a restrictive eating disorder defined by extreme avoidance of certain foods or a limited overall intake—whether in amount, variety, or both—due to sensory sensitivities, fear of negative consequences (like choking or vomiting), or a general lack of interest in food, says Rosen.

“ARFID isn’t driven by body image concerns and goes beyond ‘picky eating,’” says Simmons. “Eating becomes a source of anxiety rather than nourishment.”

ARFID can affect people of all ages, although it’s more commonly diagnosed in children. While mild food selectivity is common, ARFID causes significant anxiety, nutritional deficiencies, or interference with daily life.

Physical signs

Physical effects of ARFID often relate to nutrient deficiencies or inadequate calorie intake. Because the cause isn’t weight-focused, people may not recognize that the issue is an eating disorder. According to Simmons, signs can include:

- For children, slow growth or falling off the growth curve

- Weight loss or failure to gain expected weight

- Fatigue, low energy, or trouble concentrating

- Digestive issues like constipation or stomach pain

- Pale skin, brittle hair, or weak nails

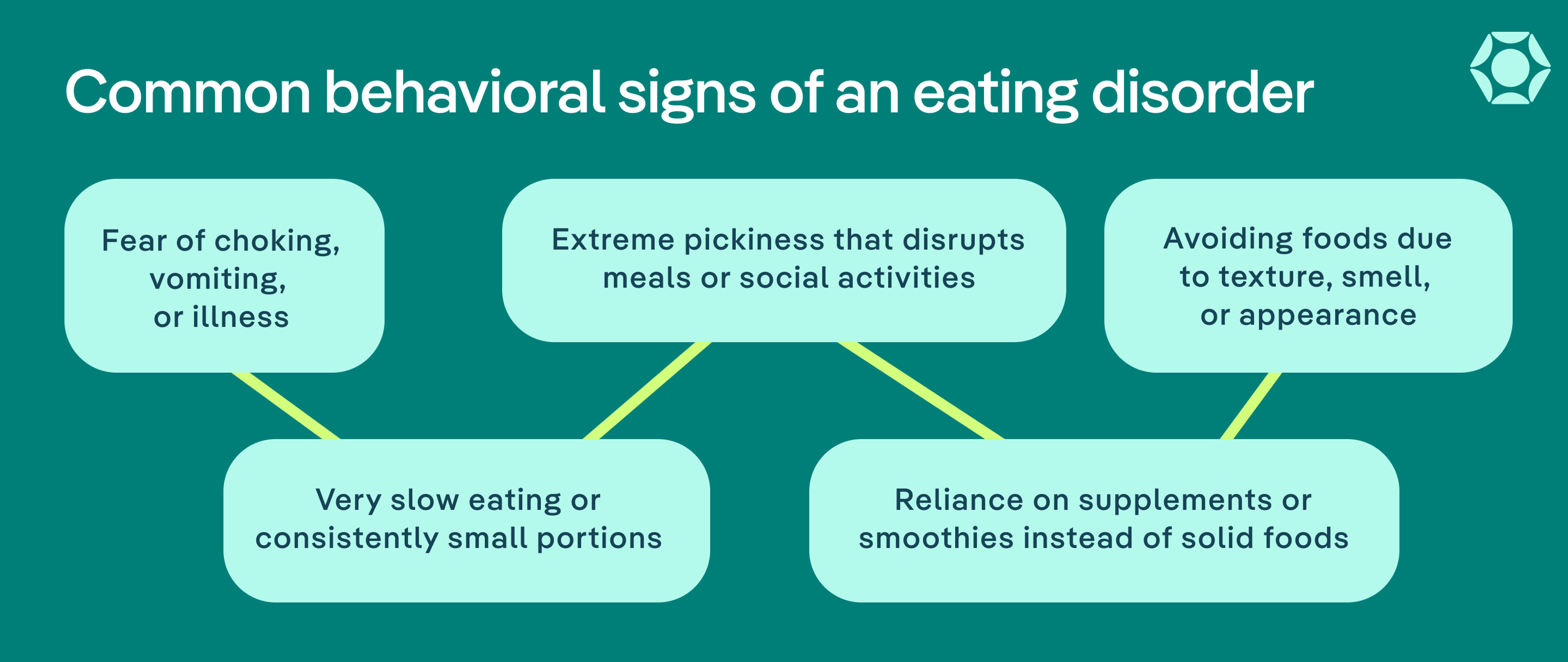

Behavioral signs

Behavioral patterns in ARFID often center on avoidance, rigidity, or distress related to specific foods or eating environments. Here’s what to look out for, according to Rosen:

- Avoiding foods because of texture, smell, or appearance

- Fear of choking, vomiting, or getting sick

- Extreme pickiness that disrupts family meals or social life

- Eating very slowly or only small amounts at a time

- Relying on supplements or smoothies instead of solid foods

Emotional and cognitive signs

“Emotionally and cognitively, there’s genuine fear or disgust surrounding certain foods, which can cause mealtimes to feel tense,” says Simmons. That can look like:

- Fear or disgust around specific foods

- Tantrums or anxiety before or during meals

- Little interest in food or pleasure from eating

- Avoidance of social situations involving food

- Feeling misunderstood or embarrassed about eating difficulties

What are signs of other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED)?

“OSFED is a category for eating disturbances that cause significant distress but don’t fit neatly into other categories,” says Simmons.

Because OSFED can take many forms, the signs and symptoms often overlap with those described in the previous sections, such as changes in mood, food rituals, or secrecy around eating. The main difference lies in how these symptoms combine and present. For example, some people might eat restrictively but not be underweight; others might purge without bingeing or experience distressing nighttime eating patterns.

Below are some of the most common OSFED subtypes and the signs to look for in each.

Atypical anorexia nervosa

People with atypical anorexia experience almost all the same symptoms as those with anorexia, but are not underweight. Still, AAN is just as serious and even more common than AN. Symptoms can include:

- Restricting food despite hunger due to fear of weight gain or a need for control

- Preoccupation with calories or “healthy” eating that causes anxiety or guilt

- Distress about body size or shape even when weight is stable or below average

Purging disorder

People with purging disorder, engage in purging behaviors without binge eating. Signs include:

- Going to the bathroom right after meals to induce vomiting

- Misusing laxatives, diuretics, or diet pills as “cleansing” or “detoxing” methods

- Guilt, shame, or anxiety after eating that triggers purging

Night eating syndrome

Night eating syndrome involves consuming a significant portion of daily calories after dinner or during nighttime awakenings. It’s often tied to emotional stress or disrupted sleep cycles, and can look like:

- Eating late at night or after waking from sleep, often feeling unable to stop

- Little or no appetite in the morning due to shifted hunger cues

- Shame, secrecy, or embarrassment about nighttime eating

Unspecified or mixed patterns

Some people experience a blend of symptoms from multiple eating disorders that don’t match a single diagnosis. For instance, someone might alternate between restriction and bingeing, or cycle through different disordered behaviors at various points in time. Common patterns include:

- Fluctuating control around food and eating behaviors

- Persistent anxiety about food, exercise, or body image

- Feeling like something is “off,” even without fitting a specific label

Why do some eating disorder signs go unnoticed?

Despite how common eating disorders are, they often go undetected for months or even years.

“Eating disorders are deceiving and camouflage themselves as ‘healthy’ changes such as cutting out carbs, becoming vegan, tracking macros, or exercising more,” says Simmons. “Culturally, these habits are often praised, which can delay recognition.”

This can be especially true for athletes, whose intense training schedules and rigid nutrition routines are often viewed as dedication or even required for performance. Behaviors like pushing through injuries, restricting food for weigh-ins, or obsessively tracking calories or macros can be dismissed as part of the sport, making it harder for coaches, parents, and teammates to recognize when these habits cross into disordered or dangerous territory.

Below are a few reasons these warning signs are easy to overlook—and what to pay attention to instead.

They hide behind diet culture

Diet culture normalizes restriction, calorie counting, and the pursuit of thinness as signs of health. When disordered behaviors—like skipping meals or avoiding food groups—are socially rewarded, it becomes harder to recognize them as red flags, says Simmons. Over time, this makes it easy to dismiss early symptoms as “just being healthy.”

They don’t always look the way people expect

Many people still associate eating disorders with extreme thinness, but that stereotype is inaccurate and harmful. Research shows that most people with eating disorders are not underweight, and symptoms can occur in bodies of all sizes. This misconception prevents countless people—especially those in larger bodies—from being diagnosed or taken seriously.

Eating disorders are also underrecognized in people who don’t fit the narrow cultural stereotype of who gets them, including boys and men, people of color, LGBTQ+ individuals, and those with limited access to care. Bias in healthcare, stigma, and cultural assumptions about who is “at risk” can delay or block diagnosis, leaving many people without the support they need.

They happen in private

Many symptoms—like purging, bingeing, or overexercising—happen in private spaces, making them difficult to spot even for close friends and family, says Rosen.

That’s why it’s so important to trust your gut if something feels off, adds Simmons. Subtle changes in routine, personality, or social engagement can be just as revealing as visible physical signs.

They overlap with mental health symptoms

Anxiety, perfectionism, and depression often accompany eating disorders. Because these symptoms can exist on their own, it’s easy to focus on the emotional distress and overlook the disordered behaviors driving it.

“When anxiety increases and flexibility decreases, that’s a red flag,” explains Simmons.

How to help someone showing signs of an eating disorder

Reaching out to someone you’re worried about can feel uncomfortable, but it can make a meaningful difference. Many people with eating disorders don’t recognize the severity of their symptoms or may feel too ashamed to ask for help, and early intervention is linked to better outcomes and a shorter, less severe course of illness. Your voice may be one of the first signals that something is wrong and that they don’t have to navigate it alone.

“If something feels off, it’s important to approach your loved one with care by staying calm, nonjudgmental, and compassionate,” says Rosen.

Here’s what she and Simmons recommend:

- Start with curiosity, not confrontation: The goal isn’t to diagnose or force someone to eat—it’s to open the door for support. Express what you’ve noticed in a caring, factual way, and focus on how they’re feeling, not how they look. You might say something like, “I’ve noticed you’ve seemed anxious around food lately, and I’m concerned because I care about you.”

- Avoid commenting on appearance, weight, or willpower: Even well-meaning remarks like “You look great” or “I wish I had your discipline” can reinforce harmful beliefs. Keep the focus on emotional well-being instead.

- Offer tangible support: Once the conversation is open, help make next steps easier and help them find professional care.

- Focus on feelings, not food: Eating disorders aren’t really about food—they’re about emotional pain and a need for control. Ask how they’ve been coping with stress or change rather than focusing on what or how much they’re eating.

- Know what not to do: Even with good intentions, some reactions can make recovery harder. For young people with eating disorders, parents do play a role in supervising meals during recovery, but it's important to do this with the support of a treatment team.

- Keep showing up: Recovery is rarely linear, and relapse doesn’t mean failure. Keep checking in, sharing meals when appropriate, and reminding them that you care, regardless of what they eat or weigh.

“The most important message to anyone suffering is that recovery is absolutely possible, especially when families act early, stay connected, and hold hope when their loved one cannot,” says Simmons.

For parents and caregivers of children and teens, that sometimes means seeking an evaluation or treatment even if your child is not ready or doesn’t believe they need help. Caregivers play a critical role in early intervention, and taking action sooner rather than later can be lifesaving.

How to seek help

If you’re wondering how to know if you have an eating disorder, or if you’re worried about someone you care about, there are clear, supportive paths to finding the right care:

- Start with self-reflection or a screener: If you’re unsure whether what you’re experiencing “counts,” try Equip’s free eating disorder screener. It can help you identify patterns in your or your loved one’s relationship with food, exercise, or body image and suggest next steps for support.

- Talk to your primary care provider or a mental health professional: Be open about what you’ve noticed. A clinician familiar with eating disorders can evaluate your symptoms and connect you to specialized care.

- Look for eating disorder–specific treatment programs: Evidence-based care often includes a team of professionals—such as a therapist, dietitian, and medical provider—working together.

- Involve trusted family or friends: Recovery is hard to face alone. If possible, share what you’re going through with someone you trust. Loved ones can help with accountability, meal support, and emotional encouragement.

- If you’re supporting someone else, seek help for yourself too: Parents, partners, and friends often benefit from professional guidance on how to navigate communication, boundaries, and self-care while supporting someone with an eating disorder.

- Reach out early: You don’t need to wait until symptoms are “severe enough.” Early intervention is linked to faster recovery, lower relapse rates, and better long-term health outcomes.

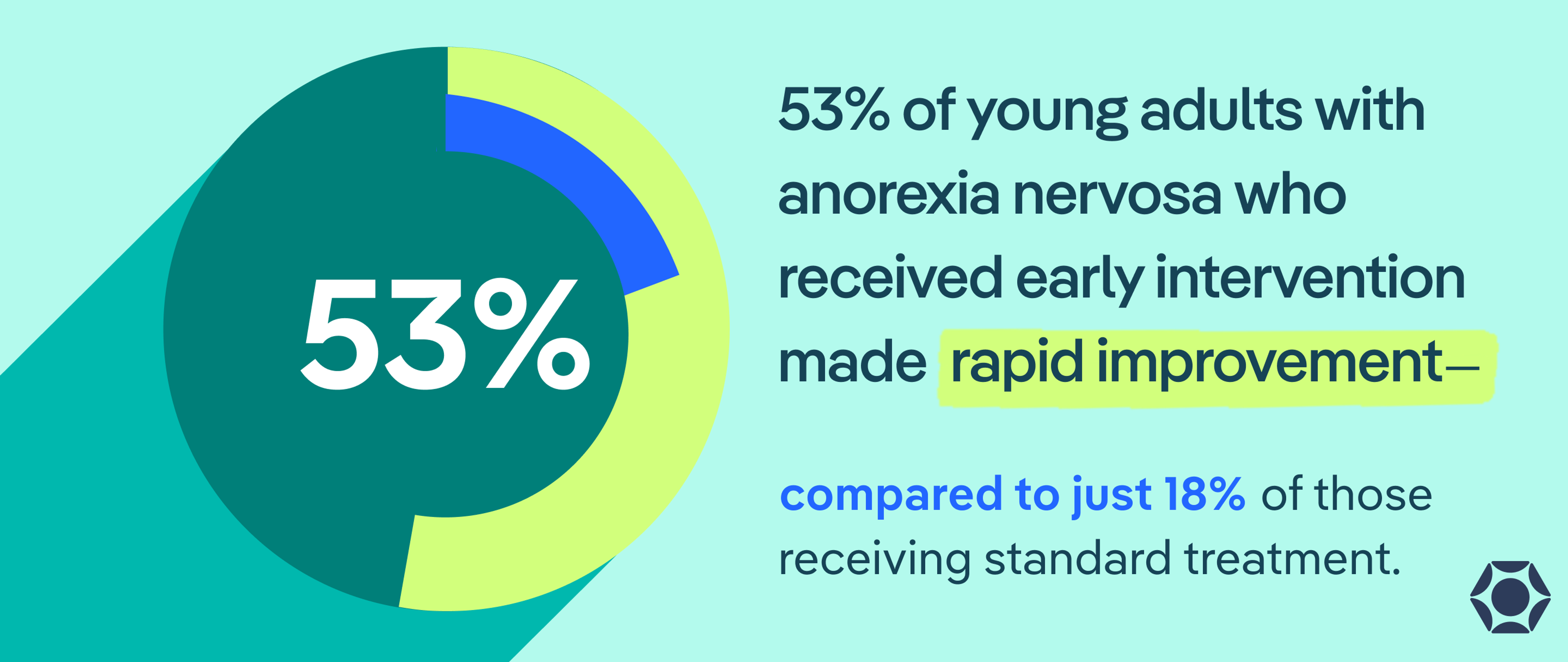

The importance of early intervention

Recognizing the signs of an eating disorder is an important first step, but getting help early is what truly changes outcomes.

In one study, 53% of young adults with anorexia nervosa who received early intervention made rapid improvement, compared to just 18% of those receiving standard treatment. Acting quickly can shorten the course of illness, reduce hospitalizations, and restore healthy behaviors before they become deeply ingrained.

If you notice even subtle warning signs—whether in yourself or a loved one—don’t wait for symptoms to worsen or become “serious enough.” Seeking support early is not overreacting; it’s proactive care. Equip’s free eating disorder screener can be a first step toward understanding what’s going on and connecting to evidence-based treatment.

The bottom line

Eating disorders can look different for everyone. What often unites them is the silence, shame, and secrecy that make them hard to spot (and even harder to talk about).

Awareness is the first step toward change. Paying attention to emotional shifts, subtle behavioral patterns, and your gut instincts can help you recognize when something isn’t right. Whether you’re noticing these signs in yourself or someone else, responding with compassion is a critical step in getting the support needed to recover from this serious illness. Early, caring intervention can make all the difference.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is forgetting to eat an eating disorder?

Occasionally skipping a meal due to stress or distraction isn’t necessarily an eating disorder. But regularly “forgetting” to eat, ignoring hunger cues, or feeling disconnected from your body’s needs can be early signs of disordered eating or restrictive patterns.

Can you have an eating disorder without knowing?

Yes. Many people don’t recognize that their eating or exercise habits are disordered, especially if they seem “healthy” or are praised by others. Because eating disorders develop gradually and thrive in secrecy, it’s common for people to realize something is wrong only after symptoms worsen.

What is the difference between dieting and an eating disorder?

Dieting typically involves short-term changes to eating habits for a specific goal, like weight loss or fitness. An eating disorder, on the other hand, is a mental health condition that involves persistent, distressing thoughts and behaviors around food, body image, and control.

ANAD. “Eating Disorder Statistics | ANAD - National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders.” Anad.org, 29 Nov. 2023, anad.org/eating-disorder-statistic/.

Austin, Amelia et al. “The First Episode Rapid Early Intervention for Eating Disorders - Upscaled study: Clinical outcomes.” Early intervention in psychiatry vol. 16,1 (2022): 97-105. doi:10.1111/eip.13139

Balasundaram, Palanikumar, and Prathipa Santhanam. “Eating Disorders.” National Library of Medicine, StatPearls Publishing, 2023, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567717/.

Borowiec, Joanna et al. “Eating disorder risk in adolescent and adult female athletes: the role of body satisfaction, sport type, BMI, level of competition, and training background.” BMC sports science, medicine & rehabilitation vol. 15,1 91. 25 Jul. 2023, doi:10.1186/s13102-023-00683-7

Iqbal, Aqsa, and Anis Rehman. “Binge Eating Disorder.” PubMed, StatPearls Publishing, 2022, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551700/.

Jain, Ashish, and Musa Yilanli. “Bulimia Nervosa.” PubMed, StatPearls Publishing, 31 July 2023, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562178/.

Keel, Pamela K. “Purging disorder: recent advances and future challenges.” Current opinion in psychiatry vol. 32,6 (2019): 518-524. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000541

Koreshe, Eyza et al. “Prevention and early intervention in eating disorders: findings from a rapid review.” Journal of eating disorders vol. 11,1 38. 10 Mar. 2023, doi:10.1186/s40337-023-00758-3

Medline Plus. “Eating Disorders.” Medlineplus.gov, National Library of Medicine, 2019, medlineplus.gov/eatingdisorders.html.

Moore, Christine A, and Brooke R Bokor. “Anorexia Nervosa.” National Library of Medicine, StatPearls Publishing, 2023, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459148/.

Roberts, Karyn J, and Eileen Chaves. “Beyond Binge Eating: The Impact of Implicit Biases in Healthcare on Youth with Disordered Eating and Obesity.” Nutrients vol. 15,8 1861. 13 Apr. 2023, doi:10.3390/nu15081861