- Anorexia and bulimia are two of the most well-known eating disorders. They share some similarities, but are distinct diagnoses.

- Anorexia is primarily characterized by food restriction, while bulimia is characterized by recurrent episodes of binge eating followed by purging to "get rid of" the food.

- Anorexia binge-purge subtype (AN-BP) also includes binge-purge behaviors. The main difference AN-BP and bulimia is that AN-BP involves a low body weight.

- The label isn't as important as getting help. Eating disorders can do significant harm and require professional treatment, regardless of the specific behaviors or diagnosis.

Many people mistakenly believe that anorexia and bulimia are essentially the same illness, with a few small differences. And while it’s true that the diagnoses have a fair amount in common, they vary significantly when it comes to symptoms, behaviors, risk factors, health impact, and treatment approaches. Understanding those differences can be essential for getting the right help—and finally recovering from disordered eating. In this article, we’ll cover everything you need to know about both anorexia and bulimia, so you or your loved one can get the right care.

What is anorexia?

Anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder that causes people to severely limit how much food they eat (skipping meals, fasting, only eating low-calorie foods, etc.), resulting in dangerous weight loss. In some cases, this weight loss can be so severe that it’s life-threatening: anorexia has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder, with approximately 5% of patients dying within four years of the diagnosis.

Unlike ARFID, another eating disorder characterized by food restriction, anorexia isn’t about pickiness or lack of interest in food. According to the DSM-5, people with anorexia limit their food intake due to an intense fear of gaining weight, often accompanied by a distorted self-image (called “body image disturbance”).

“Those with anorexia can point out anyone around them who's too thin or who doesn't look healthy, but they really struggle to see their own self in that same light," says Maria La Via, MD, Director of Psychiatry at Equip. "I always tell people that body image disturbance is like looking at yourself in a fun house mirror.”

It's important to note that while this eating disorder is most commonly diagnosed in girls and women, men and boys can struggle with anorexia, too. Similarly, it can affect people of any age (including children), race, or body size (you do not need to be underweight to have anorexia—more on that below).

The 3 types of anorexia nervosa

While many people think of anorexia as a single condition, mental health professionals recognize that it can show up in different ways, and change over a person's life span. In fact, there are three distinct subtypes of anorexia.

Anorexia nervosa restricting type (AN-R)

Anorexia nervosa restricting type is what most people picture when they think of anorexia. It is characterized primarily by extreme food restriction, sometimes alongside disordered exercise behaviors, both of which are driven by a fear of weight gain and body image distress.

“These are people who really minimize what they eat and exercise to decrease weight,” says La Via. This might look like skipping meals, eating only very low-calorie foods, and working out excessively.

Like with other eating disorders, those with this type of anorexia will often try to hide their behaviors from others. “They’ll put in an effort in social situations to look like they're eating even when they’re not,” La Via says. “They might push things around on their plate, or claim they're not hungry or have eaten prior.”

Anorexia nervosa binge-eating/purging type (AN-BP)

People with anorexia binge-purge subtype limit their food intake, like those with anorexia nervosa restricting type. But they also experience episodes of binge eating—or uncontrolled overeating—followed by behaviors that are meant to “undo” the amount of calories they’ve consumed, called “purging.”

“Purging could involve throwing up, using laxatives, diuretics or water pills, or excessively exercising. Essentially, it's any compensatory behavior to ‘make up’ for binge eating,” says La Via.

Atypical anorexia nervosa (AAN)

In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), atypical anorexia officially falls under the diagnostic umbrella of OSFED, not anorexia—but it is a form of anorexia. People who struggle with this type of anorexia exhibit all the psychological and behavioral symptoms of anorexia—body image disturbance, food restriction, etc.—but remain within or above a "normal" weight range. The term “atypical anorexia” is actually misleading, as this subtype is actually more common than the other types of anorexia: it affects up to 4.9% of people, while the lifetime prevalence for the other two subtypes is estimated to be 0.6%

“A patient of mine who had been over 300 pounds lost half of her body weight, but because 150 pounds for her height was considered normal for her age, sex, and height, she didn't technically meet the criteria for anorexia nervosa. But, in every other way, she behaved like someone with typical anorexia nervosa,” says La Via.

It’s important to note that AAN carries almost all of the same mental and physical health risks as AN-BP and AN-R.

What is bulimia?

While bulimia and anorexia can both involve body image disturbance and restrictive eating, they are different diagnoses. Similar to anorexia, bulimia can involve restricting food, but it is primarily characterized by a repeated cycle of binge eating followed by compensatory behaviors to "undo" what was consumed. These purging behaviors can take a variety of different forms, including self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives or diuretics, or excessive exercise, among others.

"A lot of my patients have what's called their 'witching hour,' or when they engage in these binge-purge behaviors," says Debra Spector, MS, RDN, CDN. "The most common 'witching hours' I find in my practice are after school or at night after long periods or days of restriction."

It's important to understand, Spector explains, that bingeing is distinct from simply overeating: "Bingeing always has an emotional component and intentionality to it that’s not associated with overeating.”

According to the DSM-5, a formal diagnosis of bulimia requires at least one binge/purge episode a week for three months. And while this eating disorder can emerge at any point in the lifespan, the median age of onset is around 18 years old. Research also shows that 68% of people with bulimia have at least one anxiety disorder, and about 30% of people have a co-occurring substance use disorder.

What's the difference between anorexia binge-purge type and bulimia nervosa?

The most important distinction between anorexia and bulimia is weight.

“Bulimia nervosa can look like anorexia nervosa binge-purge type, except for the fact that those with anorexia nervosa are significantly low in weight. With bulimia nervosa, people tend to be in a relatively healthy weight range,” says La Via.

Health risks of anorexia vs. bulimia

Both anorexia and bulimia are serious health issues that can severely impact a person's ability to function and thrive—and they both present specific health risks that are important to understand.

Health risks of anorexia:

- Bone loss and osteoporosis

- Heart problems (bradycardia, arrhythmias)

- Hair loss and brittle nails

- Amenorrhea (loss of menstruation)

- Muscle wasting

- Kidney problems

- Hypothermia and cold intolerance

- Cognitive impairment

- Death

- Delayed puberty

Health risks of bulimia:

- Dental erosion and tooth decay (from vomiting)

- Electrolyte imbalances (potentially fatal)

- Dehydration

- Swollen salivary glands

- Chronic sore throat

- Digestive problems and constipation

- Heart irregularities (from electrolyte disruption)

- Chronic fatigue

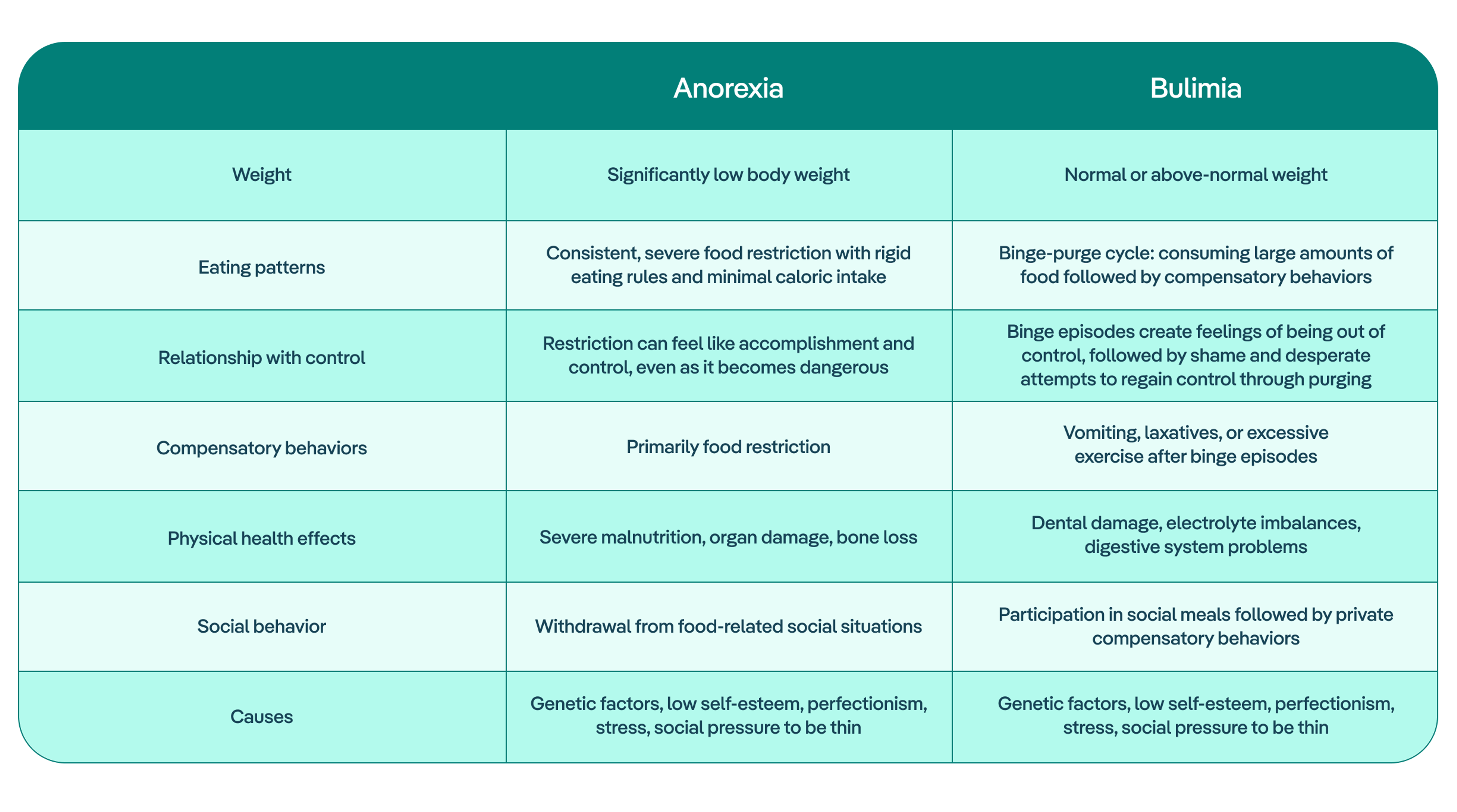

Summary of key differences between anorexia vs. bulimia

It’s important to understand that eating disorders are complex and nuanced, and can manifest differently from person to person. It’s also common for those struggling to move from one diagnosis to another before they get help. That said, the chart below provides a simplified, at-a-glance overview of the differences between anorexia and bulimia.

Is anorexia treatment different from bulimia treatment?

Both anorexia and bulimia require multidisciplinary care, or collaborative support from a team of professionals like medical doctors, therapists, dietitians, and sometimes psychiatrists. Likewise, both require evidence-based treatment modalities and ongoing professional support for full recovery.

Below we explore some of the key similarities and differences between treatment for anorexia and bulimia.

Primary focus

Because people with anorexia are often severely underweight, immediate medical stabilization and weight restoration (or weight gain) are typically the primary focus. After that, people often work with a registered dietitian to develop meal plans and strategies for eating, with the goal being to establish regular eating habits.

With bulimia, weight restoration is rarely needed since most people maintain a normal weight. Instead, clinicians will focus on normalizing eating patterns, reducing binge episodes, and stopping purging behaviors like vomiting or laxative use.

Therapeutic modalities

There are a number of evidence-based treatment modalities for eating disorders, and many can be used for both anorexia and bulimia. Family-based treatment (FBT) is the gold standard modality for treating eating disorders in young people, and this will typically be the first line treatment option for young people with both anorexia and bulimia.

For adults with anorexia and bulimia, both enhanced cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT-E) and dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), which helps with emotion regulation, are effective interventions. DBT in particular has been shown to be incredibly successful: a study on women with anorexia found that after an average of 21.7 weeks of DBT, 35% of patients were in full remission, and an additional 55% were in partial remission. The specific modalities used will depend less on the specific diagnosis, and more on a patient’s individual needs and challenges.

Timeline and intensity

Because people who struggle with anorexia are often severely underweight, they might initially need higher levels of care (inpatient/residential). Those struggling with anorexia also have high rates of relapse, which may mean that they need to remain in treatment for longer to ensure they are set up for sustainable, lasting recovery.

Bulimia recovery, however, typically starts in outpatient treatment, focusing on behavioral recovery. Patients only move to inpatient programs if medically necessary, which might be the case if purging behaviors are extreme enough to lead to electrolyte disturbances (which can be fatal).

How do I know if I have anorexia vs. bulimia?

While people can experience a mix of bulimic and anorexic behaviors or shift between them over time, there are key signs to look for that can indicate which diagnosis you or a loved one are struggling with.

Those experiencing anorexia might:

- Be significantly underweight

- Eat very little, skip meals, or follow rigid food rules ("safe" vs "unsafe" foods)

- Feel cold all the time, tired, or dizzy when standing up

- Exercise excessively to burn off any calories eaten

- Feel proud or accomplished after restricting food

- Avoid eating in front of others or make excuses to skip meals

Those experiencing bulimia might:

- Have episodes of eating large amounts quickly while feeling out of control

- Feel panic/guilt after eating and try to "undo" it through vomiting, laxatives, or intense exercise

- Plan their day around when binge and purge episodes

- Withdraw socially or experience mood changes

Anorexia vs. bulimia: Next steps for getting help

It’s important to note that you do not need a formal diagnosis to get support. The specific label isn't as important as recognizing that your relationship with food is causing distress and interfering with your life—and knowing that you deserve help.

Whether you or a loved one is struggling, it’s normal to feel hesitant to reach out for support. “There can be so much shame and embarrassment around eating disorders that prevent people from getting help sooner,” says Spector. “But early intervention is what really saves lives.”

Regardless of whether you or someone you know is struggling with bulimia or anorexia tendencies—or even a mix of both—help is available. With the right multidisciplinary care team and approaches, recovery is possible for everyone. Schedule a free consultation with an Equip team member today to talk through your concerns and discuss treatment options.

- National Institute of Mental Health. "Eating Disorders." National Institute of Mental Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/eating-disorders. Accessed 29 Sept. 2025.

- Auger, Nathalie et al. “Anorexia nervosa and the long-term risk of mortality in women.” World psychiatry: official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA) vol. 20,3 (2021): 448-449. doi:10.1002/wps.20904

- Harrop, Erin N et al. “Restrictive eating disorders in higher weight persons: A systematic review of atypical anorexia nervosa prevalence and consecutive admission literature.” The International journal of eating disorders vol. 54,8 (2021): 1328-1357. doi:10.1002/eat.23519

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. "Table 20DSM-IV to DSM-5 Bulimia Nervosa Comparison." DSM-5 Changes: Implications for Child Serious Emotional Disturbance, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, June 2016. NCBI Bookshelf, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519712/table/ch3.t16/. Accessed 29 Sept. 2025.

- Kaye, Walter H., et al. "Comorbidity of Anxiety Disorders With Anorexia and Bulimia Nervosa." American Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 161, no. 12, Dec. 2004, pp. 2215-21, https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2215.

- "Eating Disorders by Country 2025." World Population Review, worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/eating-disorders-by-country. Accessed 29 Sept. 2025.

- "Eating Disorder Statistics." National Eating Disorders Association, www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/statistics/. Accessed 29 Sept. 2025