If you've ever searched for food addiction help, food addiction symptoms, or food addiction treatment, you're not alone. In one study, 86 percent of people said they believe certain foods are addictive, and 79 percent said that sugar is addictive. “I often hear clients talk about being addicted to food,” says dietitian Caroline Young, MS, RD. “They feel like certain foods have power over their lives, and they can’t trust themselves around them. I hear statements like, 'I better not have X in the house, because I’m addicted.'”

It doesn't help that discussions on the news or social media tend to demonize ingredients in common foods. You might have even heard the theory that “fun” foods like pizza, fries, and anything with sugar are as addictive as drugs like cocaine and heroin.

If you feel like certain foods have a power over you, it’s not all in your head, but it’s not really “food addiction.” Read on to learn what the science says about food addiction, consider an alternative perspective, and discover solutions outside of food addiction treatment that can help you find food peace.

What is food addiction?

It's somewhat tricky to define “food addiction”, because it’s not an official condition, and so there isn't a standard definition. But when most people—researchers included—talk about food addiction, they're typically referring to eating habits around highly enjoyable foods, cravings for those foods, and feeling a lack of control when eating these foods, perhaps even bingeing on them.

“It’s not typical for people to feel this way about broccoli or bananas, or other nutrient-dense food,” Young says. “The foods typically named in relation to ‘food addiction’ are the ones diet culture calls 'junk' or 'bad' food—or what I, along with my anti-diet colleagues, call 'fun' or 'play' food. Think high-sugar, high-fat, and high-salt: cookies, cakes, pizza, and fries.”

The science behind food addiction

Like several far-reaching claims made in the nutrition world, the theory of food addiction lacks substantial evidence. A 2022 systematic review concluded that food addiction isn’t a legitimate diagnosis and there is simply not enough research or clinical trials to draw conclusions.

This is in part because there's no unanimously accepted definition of “food addiction” or well-defined diagnostic criteria for it. Many studies use the Yale Food Addiction Scale, an assessment created in 2009 that applies substance dependence criteria to food addiction. But there are many criticisms of the YFAS. For one, this measure is self-reported, meaning it's the person's own perception of their eating, which may not be completely reliable—a medical provider or even the person's friend may have a different take on that person's eating behaviors. Secondly, the scale assumes that food addition is a neurobiological disease, similar to substance use disorders. But this assumption isn't supported by the research.

Measurements aside, a handful of animal studies have found that rodents can display behaviors associated with food addiction, such as withdrawal from high-fat foods and persistent seeking of sugar. But studies haven't found that humans behave this way. Additionally, rodents act like this when they're isolated, but when they're put in a cage with other rodents, they don't seek out the sugar as much, says Dana Sturtevant, MS, RD, dietitian and co-author of the book Reclaiming Body Trust. And then there’s the overlooked issue of the impact of dietary restriction.

Why it feels like an addiction: the role of restriction and "food noise"

“A history of dieting can intensify cravings and a drive to eat, mimicking signs of what’s labeled as food addiction,” says dietitian Kristin Draayer, MS, RDN. That’s exactly what happened to the rodents in the study referenced above: they only displayed “addictive” behaviors when given intermittent access to sugar. “When given free access to sugar alongside adequate access to food and water, the rodents did not binge, suggesting that it's the deprivation, not the sugar itself, that triggers this response,” Draayer explains. There's also the famous Minnesota Starvation Experiment, in which healthy young males put on a severely calorie-restricted diet became obsessed with food (experiencing what would be referred to today as "food noise")—and then, when given free access to food again, many engaged in extreme overeating.

Subsequent studies on humans also show that intermittent fasting or other types of caloric restriction—particularly of “forbidden foods” high in fat and sugar—causes some people to develop binge eating behaviors.

How restriction fuels addiction-like behaviors

Food restriction of any kind—whether that's trying to “cut back” on calories overall, cut out specific food groups, limit certain foods, you name it—can lead to actions that resemble addictive behaviors around food. But that doesn't mean someone has an addiction.

“Human beings like to feel in control, and the minute we're told we can't have something, we want it more,” Sturtevant explains. “When we engage in restrictive eating patterns and put rules and conditions around our eating, over time our tolerance to that restraint diminishes. We get tired of controlling our food, and our body gets tired of not having enough to eat.” If, as a result, we eat something that we've labeled as “bad” or “off limits,” guilt and shame can flood in. That can lead us to make stricter food rules, Sturtevant says, which we follow until we eventually succumb to hunger and the need for food once again. Then people don't only loosen the restraints, oftentimes they really let go, leading to a “screw it plan”, as Sturtevant calls it. This is almost inevitably followed by more guilt and shame, then stricter rules, and then rinse and repeat. This is known as the binge-restrict cycle.

There's also a primal response to starvation. When our bodies don't get enough calories, our behaviors change: People may find that they become preoccupied with food, thinking about it, watching the Food Channel, reading cooking blogs and so on. They may also be sure to get every last bite when they do eat, licking plates or scraping the spoon against the bottom of the yogurt container over and over. This state of biological deprivation is the primary driver of what many call "food noise"—that feeling of constant food obsession.

Food restriction and feelings of food addiction may be worse today given diet culture, which tells us that we should or shouldn't eat certain foods. “A lot of people may think they're just watching what they eat and trying to eat healthy, but when you look at the mentality under which they're navigating the world of eating, they're dieting and just calling it something else,” Sturtevant says. “And if you don't acknowledge that you’re operating under a dieting mentality, it will be difficult to make peace with food and find long-term healing.”

What’s really going on: underlying causes of food addiction

“Given the culture we live in, there is a crisis of imagination and understanding of what is going on,” Sturtevant says. “It's rare to look at a person's relationship to food prior to these studies. They don't control for food insecurity, and we know that people who live with food insecurity have a higher risk of eating disorders and disordered eating. They're also not considering people's dieting history and history of restricting and restraining food. And if you put people with chronic dieting behaviors in a room with food they think they shouldn't be having, they're going to feel compulsive. But just because that's their experience doesn't mean it's the same thing as being addicted to heroin or alcohol.”

And while feeling addicted doesn’t necessarily mean that a person has an eating disorder, there’s often an overlap in symptoms, like food preoccupation, 'food noise', and loss of control around food. Even if someone doesn’t meet the criteria for an eating disorder, usually at least disordered eating is present. “With feelings of food addiction often stemming from a place of deprivation, there’s always the chance there could be a true underlying eating disorder,” explains Equip dietitian Shira Feldman, MPH, RD.

Emotional and psychological factors

Other emotional and psychological factors may also be at play. “I notice when clients have not yet developed adequate emotional coping or regulating tools, and only go to food to self-soothe and manage hard feelings, they seem more prone to feeling like they are addicted to food,” Young says.

We also tend to forget that food itself is emotional. “We connect through food. It's used in celebrations and the grieving process. We come together, and we heal,” Sturtevant says. JD Ouellette, Director of Lived Experience at Equip, adds that society’s messages often obscure the fact that eating is supposed to be pleasurable: “We’ve been encouraged to think of food as solely fuel and we’ve lost sight of the fact that food is also love, community, and culture—and these things give us pleasure.”

Although emotional eating often gets a bad rep, it's not always a negative thing. It's a normal way to connect and sometimes cope, though it's also important to gain awareness of when we do this and build other tools to manage during emotionally tough times.

Why food addiction treatment based on abstinence fails

Despite the availability of so-called food addiction treatment programs, there's no research to support these treatments. Worse, some of these approaches are based on substance abuse treatment protocols, where abstinence is often a necessary goal for healing and health. However, if we treat food or certain foods like a drug and try to avoid them at all costs, it not only makes it challenging to get the nutrients your body needs to function, it also makes it basically impossible to develop a healthy, positive relationship with food.

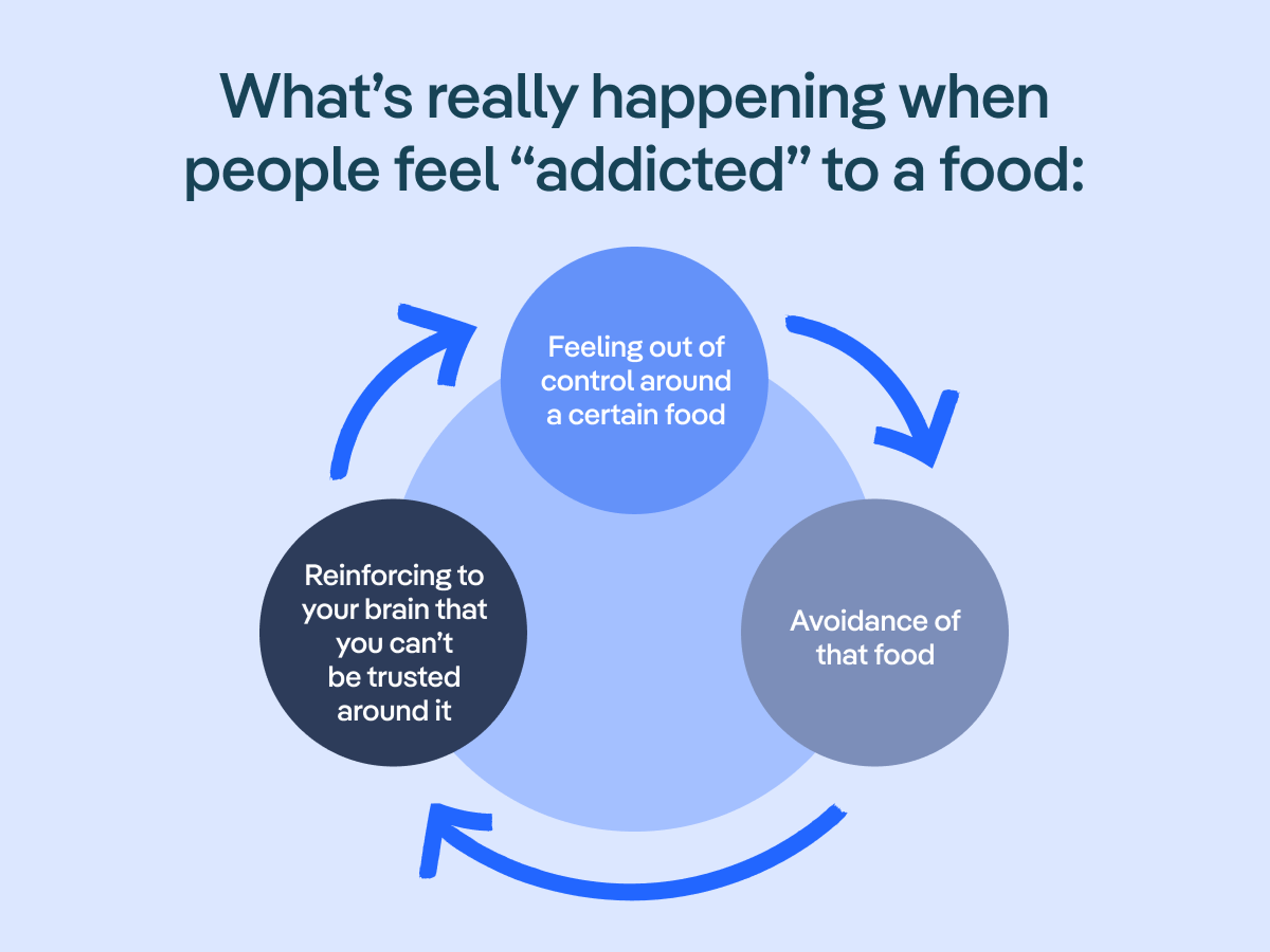

“Avoiding certain foods reinforces your belief that you can't handle them, and this thought gets wired into your brain's neural pathways,” Draayer says. “This creates a self-perpetuating cycle: You might think you're preventing out-of-control eating by staying away, but you're actually reinforcing the idea that you can't trust yourself around that food.” In other words, the rules you make to curb your “addiction” become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The core flaw: food isn't a drug

The basis for abstinence-based food addiction treatment is the idea that certain foods are as addictive as hard drugs. And it’s true that eating specific foods can light up the brain’s reward center, causing a release of dopamine—but it's not that simple. “However, what’s often left out of the conversation is that so do other things, like caring for your child or cuddling with a pet, but we don’t pathologize those behaviors,” Draayer says.

It's also unclear whether any brain changes lead to the development of a dependence on the food, as drug abuse can. Another important difference is that unlike with substance addiction, we don’t experience withdrawal symptoms when going without certain foods, and repetitively eating a food doesn’t increase our tolerance to it.

Regardless, food is a necessary part of daily life (as well as an opportunity for joy, connection, pleasure, and more), not a toxic substance, making abstinence a misguided approach that almost invariably backfires.

The evidence-based path to food addiction recovery

Firstly, if you feel like you’re addicted to food, it could be a sign of an eating disorder. Binge eating disorder is the diagnosis most often associated with feelings of food addiction, but it can also be associated with other eating disorders. Food addiction can also be linked to disordered eating, which is harmful on its own, even if you don’t have a full-blown eating disorder.

The best way to find out if an eating disorder is driving “addictive” food behaviors is to talk to your doctor or a trusted mental health professional about your concerns. You can also take a self-assessment, or get evaluated by a treatment program or professional specializing in eating disorders. Be wary of programs that offer food addiction treatment, as they are likely not evidence-based.

If an eating disorder isn't present, it's still important to get support to overcome any feelings of food addiction. Just remember that true healing isn't about how to stop food addiction through willpower, but about overcoming food addiction by breaking the binge-restrict cycle. This is the foundation of effective food addiction recovery, and the strategies below can help you get there.

Diversify your coping tools

Despite what diet culture says, using food as a coping tool is not inherently negative. However, it becomes an issue when eating is your only way to manage hard feelings and it doesn’t feel like a choice. As eating disorder therapist Anita Johnston explains, when you eat without physical hunger, you cross over into emotional symbolism: Food becomes a metaphor for what we’re needing emotionally. For instance, some people will overdo it with sweets when they’re needing love and comfort. Eating this way can satisfy emotional needs in the short-term, but they leave the root problems unaddressed, and can become a harmful pattern of behavior.

With the help of a therapist or trusted friend, you can identify what food symbolizes for you when you’re eating without physical hunger and feeling out of control, and then brainstorm ways to meet your underlying emotional needs. For the example above, people may find that spending time with their partner or pet or wrapping themselves in a blanket with a warm drink provides them the comfort they’re seeking in food.

Work toward eating adequate meals and snacks

Since restriction is often what’s driving feelings of food addiction and lack of control around food, it’s key to eat enough. Take stock of your daily eating habits and consider if you’re skipping meals, eating meals that are too small or unsatisfying, regularly missing a main macronutrient (carbs, fat, or protein), or foregoing snacks even when you’re hungry between meals. If you find gaps in your eating, work toward increasing and balancing your intake to meet your body’s needs throughout each day.

Learn about food habituation

“Habituation is a natural process that occurs when we are repeatedly exposed to the same stimulus,” Draayer explains. “Over time, our previously strong response to that stimulus decreases.” When it comes to foods that feel addicting, the more you casually expose yourself to them (instead of swearing them off), the less emotionally charged your experience becomes—cookies are just cookies, pizza is just pizza, and chips are just chips.

“Of course, certain foods will still be enjoyable, but there’s not that intense control and food obsession,” Draayer adds. “Instead, it becomes a more neutral experience, empowering people to regain control and giving them the ability to make food choices that are nourishing and satisfying.” This science-backed process is often disregarded in traditional food addiction treatment.

Keep in mind that if a food has been off-limits for a long time, a “honeymoon phase”—where you allow yourself to have however much you want of it—may be necessary before it becomes neutral. “With time, my consumption of sugary foods became more about enjoyment versus compulsion, and although my goal was not to eat less sugar, that is what happened simply because I’m able to eat it when I want and it gives me only pleasure, no shame,” Ouellette says.

Accomplishing all of the above is difficult on your own. Our team can support you with personalized, evidence-based care. Schedule a call to talk through your concerns and explore options.

Developing a healthy relationship with food

One of the most powerful ways to address any feelings of food addiction is to get curious about your relationship with food. “Much of the time, people need to work on their mindset around the foods they feel addicted to,” Feldman says. “Exploring their relationship with these foods often uncovers beliefs rooted in diet culture, and working on unpacking these beliefs is extremely beneficial.” Consider the following tips to root out harmful diet culture beliefs and develop a positive, balanced attitude toward food.

Work with a dietitian

If working toward food adequacy, food habituation, and your food relationship seems overwhelming, an eating disorder dietitian can help make the process more manageable. “There isn’t a one-size-fits-all way in which we eat, and dietitians can help people sort through all the information that is out there and find what works and feels good for them,” Feldman says.

Eat for satisfaction

Feeling full after a meal isn’t the same thing as feeling satisfied. “Satisfaction comes from pleasure,” Sturtevant says. “When we ask people about this in workshops, their most satisfying meals are about who they were with, where they were, the ambiance, the music, the service—it's more than just the food.” She encourages clients to eat for satisfaction at least once a day.

Discover what you like

“A lot of clients can't tell me if they like what they're eating. Because it hasn't been about liking it, it's about making the ‘right’ choice and how many carbs are in it or whatever external directives,” Sturtevant says. Experiment with new foods, even if that means trying a different flavor or brand of something, and listen to how your body reacts.

Let go of limitations

Sturtevant suggests making a list of your favorite foods and enjoying as much as you want, as often as you want. This may feel scary at first, but most people find that, over time, this freedom (as well as stopping any overall restriction) eliminates addictive behaviors.

Moving forward with confidence

If you're concerned that you're addicted to certain foods, you're not alone, and it’s possible to develop a healthy, neutral relationship with all foods. Working with professionals like therapists who understand eating disorders and disordered eating can help you unpack what's fueling your behaviors and develop new skills to manage your emotions. Collaborating with an eating disorder-informed dietitian can help you change your relationship with food to one that's more pleasurable and positive. You can schedule a call with an Equip team member to get connected with a dietitian and other experts who can support you on this path.

It may take time, particularly since so many messages we receive about food these days can feed into the idea that food addiction is a result of our own failure. But by learning the true roots of addictive eating behaviors, being compassionate with yourself, and enlisting professional support, you can build eating habits that feel sustainable, nourishing, and joyful. It can be challenging, but it’s so worth it.

FAQ

What is food addiction and is it a real eating disorder?

When people discuss food addiction, most are talking about having cravings for highly enjoyable foods and feeling a lack of control when eating these foods, perhaps even bingeing on them. That said, food addiction is not a real diagnosis. There's no standard definition of the term, and research on this issue is inconclusive. Many studies fail to account for people's past relationships with food, including any disordered eating, and just because a food “lights up” the same parts of the brain as drugs do doesn't make it addictive (many other things “light up” these brain regions, like cuddling a pet).

Food addiction is not an eating disorder diagnosis, but it could be a sign of an underlying eating disorder.

What are the main food addiction symptoms?

Food addiction is not an official diagnosis, so there is not one set of symptoms. Rather, when people speak of food addiction, they are often referring to an intense preoccupation with food, feeling out of control around food or certain foods, or both.

How can I stop my food addiction?

The first step toward stopping food addiction is to get evaluated for an eating disorder. If an eating disorder isn't present, you should work with a non-diet dietitian who can help you develop a more positive, balanced relationship with food and unpack any underlying concerns that might be contributing to feelings of addiction. One of the most important parts of treating food addiction is establishing regular eating habits, which helps reduce food noise and stop the binge-restrict cycle.

Why is food addiction treatment not science-backed?

Food addiction treatment is not science-backed because there haven't been any clinical trials on these programs. Most programs use substance abuse treatment techniques and apply those to food, but this approach isn’t evidence-based and can be harmful. Although abstinence is necessary and appropriate to address substance abuse, restricting food can not only lead to malnutrition but also worsen “addictive” behaviors around food.

How can dietary restriction lead to addiction-like behaviors?

Dietary restriction can lead to addiction-like behaviors because many times people set very rigid rules about what they’re not allowed to eat and, understandably, can't abide by those rules. When this happens, they may feel guilt and shame and then set even stricter limits on what they can and can't eat and in what situations. This continues until a person's primal hunger takes over, and they may binge or eat more than normal, simply because their body needs the nutrition, and then the cycle continues.

What are the psychological factors behind perceived food addiction?

Factors such as trauma, stress, early-life adversity, and mood dysregulation have been linked to perceived food addiction. In these instances, people may be using food as a tool to cope with their feelings.

What are effective alternatives to food addiction treatment?

If you’re concerned you may have food addiction, it's best to get screened for an eating disorder. Even if you don't have one, working with an experienced registered dietitian and therapist can help you create an adequate meal and snack plan that prevents compulsive eating behaviors, and also work to develop tools to properly address any underlying emotional needs.

How can I develop a healthier relationship with food?

Given today's diet culture, many people can benefit from developing a healthier relationship with food. There are many ways you can do this, including:

- Eating for satisfaction (rather than simply fullness) at least once a day

- Trying new foods to discover what you like

- Eating adequate meals and snacks throughout the day

- Working with a dietitian to help you create a plan that feels good for you

- Lee, Natalia M, et al. (2013). Public Views on Food Addiction and Obesity: Implications for Policy and Treatment. PLOS One, 8(9), e74836. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0074836

- Piccinni, Armando et al. (2021.) Food addiction and psychiatric comorbidities: a review of current evidence. Eating and Weight Disorders, 26(4), 1049-1056. doi: 10.1007/s40519-020-01021-3

- Vasiliu, O. (2022). Current status of evidence for a new diagnosis: Food addiction-A literature review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.824936

- Long, Cecilia G, et al. (2015.) A Systematic Review of the Application And Correlates of YFAS-Diagnosed ‘Food Addiction’ in Humans: Are Eating-Related ‘Addictions’ a Cause for Concern or Empty Concepts? Obesity Facts, 8(6): 386–401. doi:10.1159/000442403

- Westwater, M. L., Fletcher, P. C., & Ziauddeen, H. (2016). Sugar addiction: The state of the science. European Journal of Nutrition, 55(S2), 55–69. doi:10.1007/s00394-016-1229-6

- Blumberg, Jack, et al. (2023.) Intermittent fasting: consider the risks of disordered eating for your patient. Clinical Diabetes and Endocrinology, 9:4. doi:10.1186/s40842-023-00152-7

- De Young, Kyle P, et al. (2014.) Bidirectional associations between binge eating and restriction in anorexia nervosa. An ecological momentary assessment study. Appetite, 3:69–74. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2014.08.014

- Stewart, Tiffany M, et al. (2022.) The Complicated Relationship between Dieting, Dietary Restraint, Caloric Restriction, and Eating Disorders: Is a Shift in Public Health Messaging Warranted? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1):491. doi:10.3390/ijerph19010491

- The starvation experiment. Duke Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences. (2023, May 9). https://psychiatry.duke.edu/blog/starvation-experiment

- Raghu, S. V., & Bhat, R. (2022). Neurobiology of Food Addiction. Future Foods, 425–431. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-91001-9.00035-9

- Wiss, David A, et al. (2020.) Food Addiction and Psychosocial Adversity: Biological Embedding, Contextual Factors, and Public Health Implications. Nutrients, 12(11):3521. doi:10.3390/nu12113521

- Kalon, E, et al. (2016.) Psychological and Neurobiological Correlates of Food Addiction. International Review of Neurobiology, 129:85–110. doi:10.1016/bs.irn.2016.06.003