The information in this article originally appeared in an Equip Academy presentation. Watch the presentation here, and register for future Equip Academy events to learn about other eating disorder-related topics and earn free CE credits.

Participation in sports and athletic endeavors has wide-ranging benefits in both the short-term and the long-term. But athletes are also at an increased risk of developing an eating disorder or disordered eating, and treatment of athletes with eating disorders comes with specific considerations and challenges. In this article, we’ll look at an overview of the research on athletics and eating disorders, signs and symptoms to look out for, and best practices for supporting athletes.

Benefits of engaging in sport

Research has shown that engaging in sports positively impacts a person’s mental and physical well-being in a number of ways. After controlling for social determinants of health, engaging in athletics has been shown to have the following benefits:

- Improved physical and mental health (both immediate and long-term)

- Improved academic performance

- Motor skill development/coordination

- Strength and stamina

- Better self-esteem

- More positive body image

- Good sportsmanship

- Psychosocial development

- Lower rates of suicide

- Sense of purpose, identity, and community

- Delayed onset of substance/alcohol abuse (and fewer risky behaviors overall)

- Life and occupational skills (leadership, determination, resilience, critical thinking, communication, negotiation, time management)

- Active kids tend to become active seniors

The benefits of engaging in sports were reinforced during Covid-19, which forced worldwide closure of organized sports. During this time, the protective benefits of sports were lost, and mental health issues in athletes skyrocketed. Youth athletes are even more vulnerable than adults to the negative mental health effects of sports restriction, and the residual effects of the pandemic impacted training and performance, with many young athletes losing interest in sports. For adult athletes, the Covid-19 pandemic often led to loss of career and subsequent financial stress.

After the world of sports reopened, some Covid-era modifications remained in place. Many organizations began offering at-home training programming and remote check-ins with teammates, as well as incorporating mindfulness into their practices. Athletes returned to sports protocols, and sports psychologists began ongoing discussions about athlete mental health.

Problematic eating behaviors in athletes

Unfortunately, participation in sports also comes with an increased risk of disordered eating and exercise behaviors. Problematic eating behaviors are two to three times more prevalent in athletes than in any other group, and there’s a higher risk of eating disorders across all sports (not just weight-sensitive sports) relative to non-athletes. Estimates of eating disorder prevalence in athletes vary across the literature, ranging from 2-49%.

Among collegiate athletes:

- Prevalence estimates range from 2-19%

- One quarter have subclinical eating disorder behaviors (restrictive, binge eating, purging)

- Among D1 athletes, almost half have subclinical eating disorder behaviors

And yet despite this increased risk, athletes are actually less likely to receive a diagnosis and treatment.

Prevalence by gender

Research shows that eating disorders are more prevalent among cisgender female athletes than their male counterparts. Among distance runners, for instance, one study found that 46% of females screened positively for an eating disorder, compared with 14% of males. In another study, 26% met clinical criteria for an eating disorder, with five times more females (84%) than males (16%) reporting disordered eating behaviors.

A study of female athletes found that 91% of cisgender female athletes worried about calorie intake, 50% restricted calories to improve performance or change weight/shape, and 30% were told by a medical professional that it’s normal to miss periods.

Contributing factors

There are a number of factors that contribute to this increased prevalence of eating disorders and disordered eating among athletes. Some of these factors include:

- Excessive pressure from parents/caregivers to meet expectations

- Weight-sensitive sports (like gymnastics, wrestling, ballet)

- Poor sleep hygiene (which increases anxiety and depression)

- Child encouraged/allowed to train or perform when unwell (injury, illness)

- Belief that weight manipulation will improve performance

- Participation in public/open weigh-ins

- Sudden increase in training volume

- Weight/body-related comments by teammates

- College/high school athletes grappling with a body that is continuing to change, develop, and mature while often simultaneously trying to achieve a specific athletic aesthetic

- A traumatic sports-related occurrence, like an injury or illness, a change in coach, or retirement from sport

Despite this increased risk, athletes are actually less likely to be diagnosed than their non-athlete counterparts. This is because eating disorder behaviors—like excessive exercise, restrictive diets, or obsession with weight—are often normalized in athletic circles. This makes early intervention challenging, and often athletes struggle for a long time before the eating disorder is identified.

Body dissatisfaction among athletes

Regardless of eating disorder status, athletes often struggle with body dissatisfaction. Some contributing factors to body dissatisfaction among athletes include:

- Emphasis on leanness (sometimes called the “athletic aesthetic”)

- Changing bodies (weight or body composition)

- Growth and development affects other aspects of performance

- Feeling compelled to change body to improve an aspect of performance

These factors can all be amplified by social media, constant viewing of images of themselves, and revealing or tight-fitting uniforms.

Barriers to treatment

As mentioned above, athletes are often less likely to be diagnosed with an eating disorder and receive treatment, despite their increased risk. And in cases where athletes themselves recognize that they may have a problem, there are additional barriers that prevent them from reaching out for help. These include:

- Lack of awareness

- Biases and stereotypes about who gets eating disorders

- Disordered behaviors being normalized or praised in the sports community

- Minimization of physical symptoms by coaches

- High tolerance for discomfort

- Sense of obligation to team/coach

- Shame

- Fear of loss of opportunity/scholarship

- Concern around performance implications

- Family prioritizing sports commitments

On top of all the above, athletes might also be disincentivized, either explicitly or implicitly, from seeking help when they’re struggling. They may be held back by shame or a sense of loyalty or obligation to their coach and teammates, or they may simply be unaware that their food- and body-related thoughts are disordered. Treatment accessibility is also an issue for many, as getting treatment for their eating disorder might mean being removed from their sport and losing life-altering opportunities like a sponsorship or scholarship.

Screening for eating disorders in athletes

Eating disorder assessment measures designed for use with general populations (such as the SCOFF questionnaire and EDE-Q) have demonstrated suboptimal psychometric properties in athlete populations. Several measures to assess eating disorder risk among female athletes have been developed and validated. These include:

- Compulsive Exercise Test – Athlete Version (CET-A). This was developed to assess excessive exercise. It has been found to successfully discriminate between female athletes with and without high eating disorder risk.

- Brief Eating Disorder in Athletes Questionnaire (BEDA-Q)

- Female Athlete Screening Tool

- Physiologic Screening Test

- Eating Disorder Screen for Athletes (EDSA)

Signs, symptoms, and syndromes

There are various signs and symptoms to look out for that might indicate an athlete is struggling with an eating disorder:

- Dieting/mention of diets/orthorexia

- Sudden unprompted elimination of foods or food groups

- Weight loss (regardless of weight status)

- Withdrawal/isolation

- Frequent injury/re-injury or illness

- Fainting/lightheadedness/hypoglycemia

- Weakness/fatigue

- Anemia/nutrient deficiencies

- Training beyond what is prescribed

- Decline/plateau in performance/response to training

- Refusing to participate in team meals

- Inflexibility around which foods are consumed

- Unwillingness to fuel for practice/after practice.

RED-S

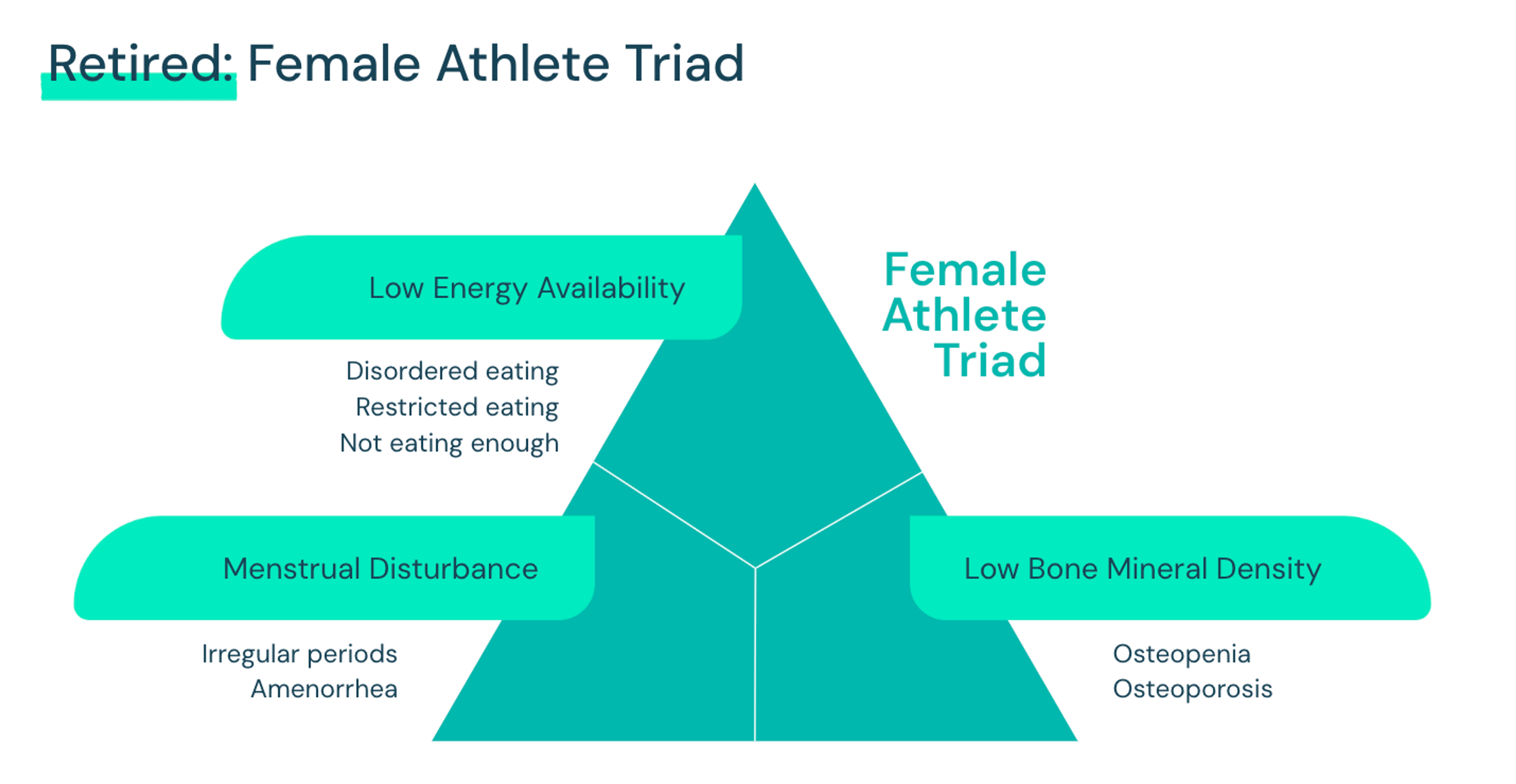

The below diagram is of the retired “female athlete triad”, which was limited to just females being flagged. The Triad at one point in history described the combination of disordered eating, amenorrhea, and early-onset bone loss (noted here as: osteopenia or osteoporosis). The latter two components (loss of menses and osteopenia/osteoporosis) are the body’s response to underfueling.

Relative Energy Deficiency in Sports (REDs) is the new, improved, and more inclusive version of the Female Athlete Triad. Coined by IOC in 2014, REDs describes the root cause of a number of performance-worsening symptoms. It is caused by inadequate energy intake relative to expenditure (regardless of eating disorder status). It is not a “triad,” but a syndrome that affects many aspects of health and athletic performance. REDs acknowledges that the consequences of underfeeding reach beyond bone and reproductive health. All athletes are vulnerable!

Some more things to know about REDs:

- It is difficult to diagnose

- In a large sample of female athletes surveyed for symptoms of REDs, 80% had one symptom, 50% had two symptoms, and 30% had over five symptoms

- 20% of studies have included males

- Consequences of low energy availability take longer to appear in males

REDs and eating disorders share many symptoms, including:

- Fatigue

- Weight loss

- Low testosterone

- Missed/irregular periods

- Frequent illness

- Hair loss

- Depression and anxiety

- Trouble focusing

- Irritability

- Trouble staying warm

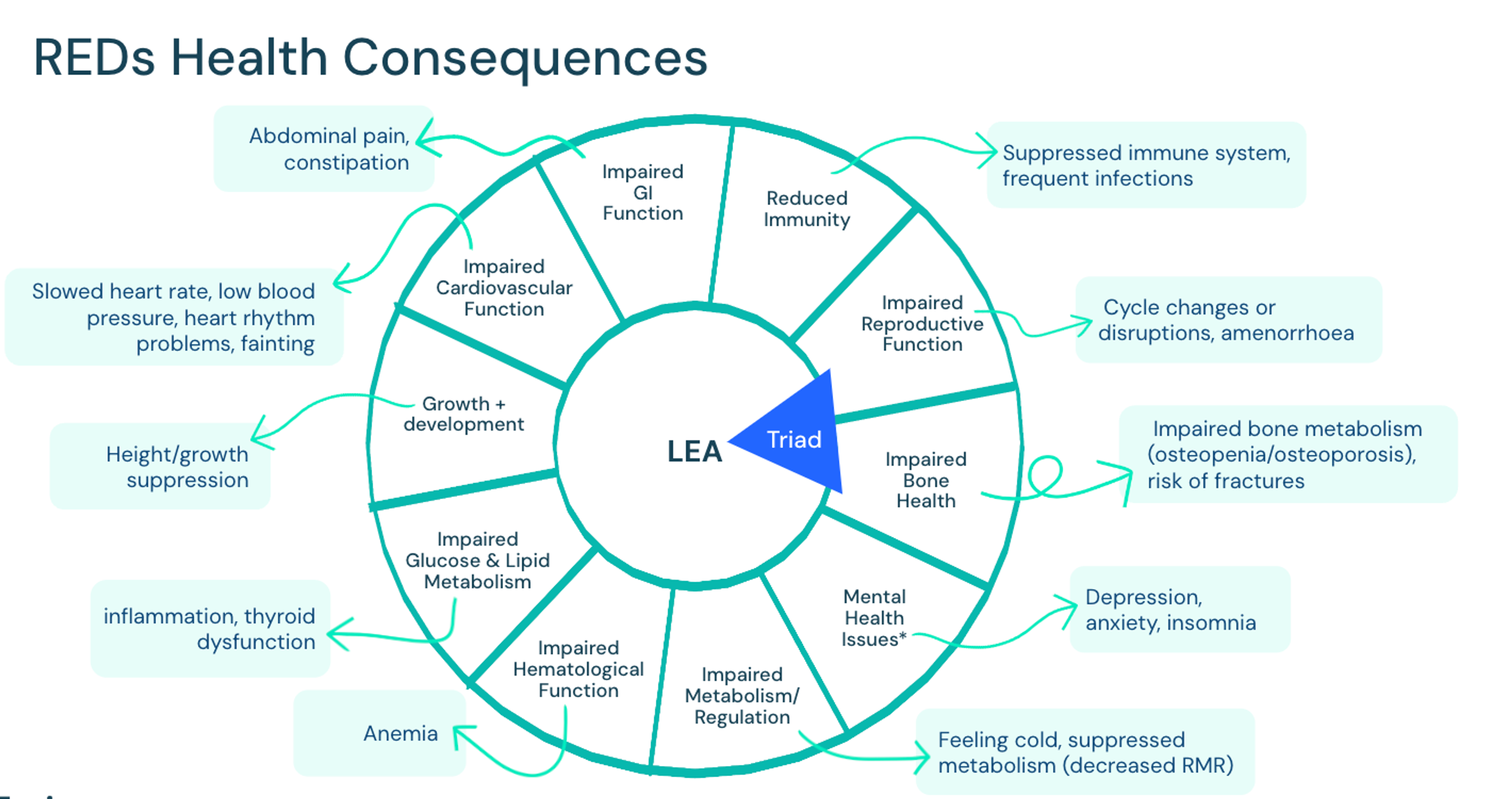

REDs has serious and far-ranging health consequences, which are illustrated in the diagram below:

Note how these symptoms truly impact the health and well-being of the individual. Here we can see the large variety or combination of symptoms that could present as a full-body syndrome, defined as a group of symptoms which consistently occur together, or a condition characterized by a set of associated symptoms.

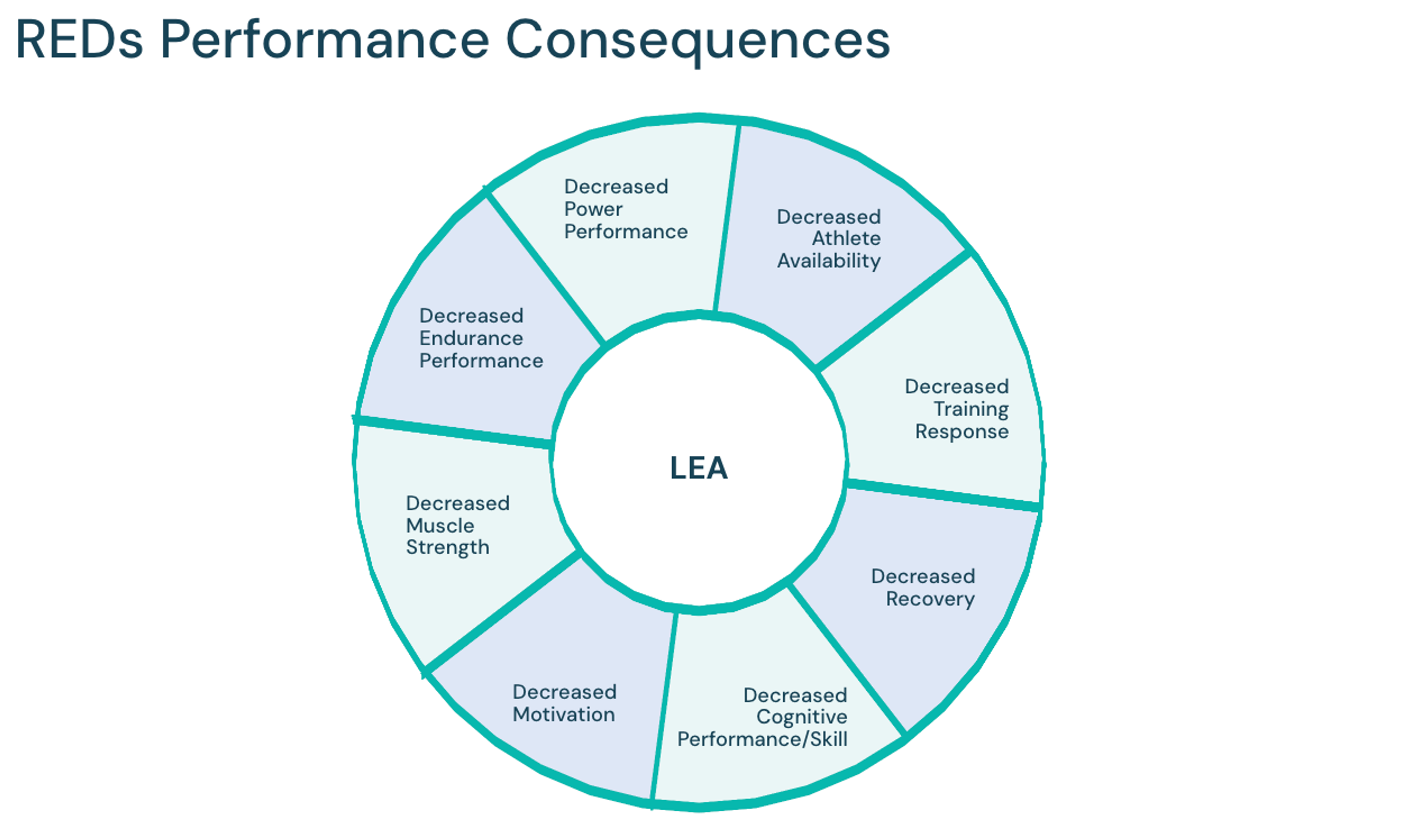

REDs also has consequences for athletic performance, illustrated in the diagram below:

Supporting an athlete with an eating disorder

It takes a village to treat an individual with an eating disorder. Guidelines are clear on recommending a team of multidisciplinary providers with training in eating disorders. The eating disorder treatment team typically includes a medical provider, dietitian, and therapist, and often a psychiatric provider as well.

When we’re talking about an athlete, that team usually also includes the athletic department, counseling, and family. Everyone on the team shares the goal of returning to sport. Not sure who will be the best supports for an athlete? Ask them!

A multidisciplinary care team for an athlete may include:

- Registered dietitian: helps with nutritional rehabilitation, meal planning, behavioral counseling, education, and weight monitoring.

- Psychologist: Helps with coping, communication, and psychological evaluation.

- Family therapist: Helps with evaluation, support, and communication skills.

- Family/parents: Help with communication, psychological support, and financial support.

- Psychiatrist: Helps with assessment, monitor safety, and provide treatment.

- Athletic administration: Help with eligibility, compliance, and financial support.

- Coach and coaching staff: Help with safe and effective training and competition.

- Team physician, athletic trainer, and physical therapist: Help with health monitoring and care.

Eating disorder treatment for athletes involves a number of different clinical areas of focus. Athlete-specific areas of focus include resolving malnourishment/LEA; return-to-sport considerations; and relationship to self, body, sport, food, and exercise.

Practice applications

When treating an athlete with an eating disorder, it’s important to understand sport culture and identity within sport. This will vary across sports, teams, age, gender, level of competition, and coaching environment.

Providers can learn more about athletes needs and how to support them with exploratory questions, such as:

- What got you into your sport? What do you love about your sport? Has that shifted at all over time?

- Can you tell me a bit about the culture on your team?

- What aspects of being an athlete bring you the most joy? Which do you struggle with the most?

- What does “sports nutrition” mean to you? What does it look like to “eat like an athlete”?

- What are the top five words that come to mind when you think about how you feel when you’re training? Competing?

- How do you tend to tolerate rest days? What do you do instead?

- Can you tell me about how you handled a time where you had to pause due to illness, injury, etc?

- How are your expectations different from/similar to your coach/teammates?

Target weight assessment

When determining a target weight for athletes with an eating disorder, it’s important to take into account a number of different factors, including:

- How new they are to athletics/training. If they are new, it is difficult to rely on historical growth data, as they may have changes in body composition that warrant a different weight target than what we predict from growth charts.

- Age/developmental stage

- Sex hormones. It may take longer for hormones to normalize if weight is advanced too soon (especially for those with propensity toward more rapid muscle development)

- Bone density. Bone loss may warrant a more conservative (i.e., higher) target, especially when unable to use hormone profile/menstruation as indication.

When setting target weights for athletes, be sensitive to their unique circumstances. Consider real and imagined consequences of aiming for a higher end of the weight range, especially in sports that have a particular idealized aesthetic. Remember that they may experience loss of respect, opportunities, and other consequences, and that this is their community, livelihood, and future—their “life worth living” outside of treatment. Remember that frequent re-evaluation of target weight is important, given many moving parts (and is also influenced by injury, off-season, retirement/transition out of sport)

Needs assessment through a sports nutrition lens

Creating meal plans and establishing energy demands for athletes requires a different approach than with non-athletes. Consider that their energy needs are already high, and will be higher to maintain a higher weight—don’t set patients up for failure with too low of a calorie target.

Considerations to keep in mind:

- Expect a wider range of needs and multiple adjustments

- More challenging to predict endpoint due to many moving parts

- Timing of meals and snacks (pre/during/post-season)

- Hydration needs change

- Macronutrient needs change (depending on sport/goals)

Use of treatment contracts

Treatment contracts can be an effective tool when treating athletes with eating disorders. Benefits include helping with clarity, increasing alignment across the board, and appealing to the coachability of an athlete who has traits of being goal-oriented.

These contracts can be developed early on in treatment with patients, and can be shared with all people involved in a patient’s treatment. Treatment contracts may be best introduced during transitions, for instance if the patient is making a rapid transition from intensive outpatient treatment and back into the sport, patient is not fully reintegrated, or patient struggles with maintaining adequate intake. Contracts can be extremely supportive to creating alignment between the patient, their supports, and the treatment team.

Treatment contracts typically include:

- Expectations for participating in treatment (session attendance, labs, weight checks)

- Frequency of meals and snacks

- Weight/intake goals

- Consequences/rewards for meeting/not meeting targets

- Supportive vs. punitive guidelines

- Clear and firm language

Athlete programming at Equip

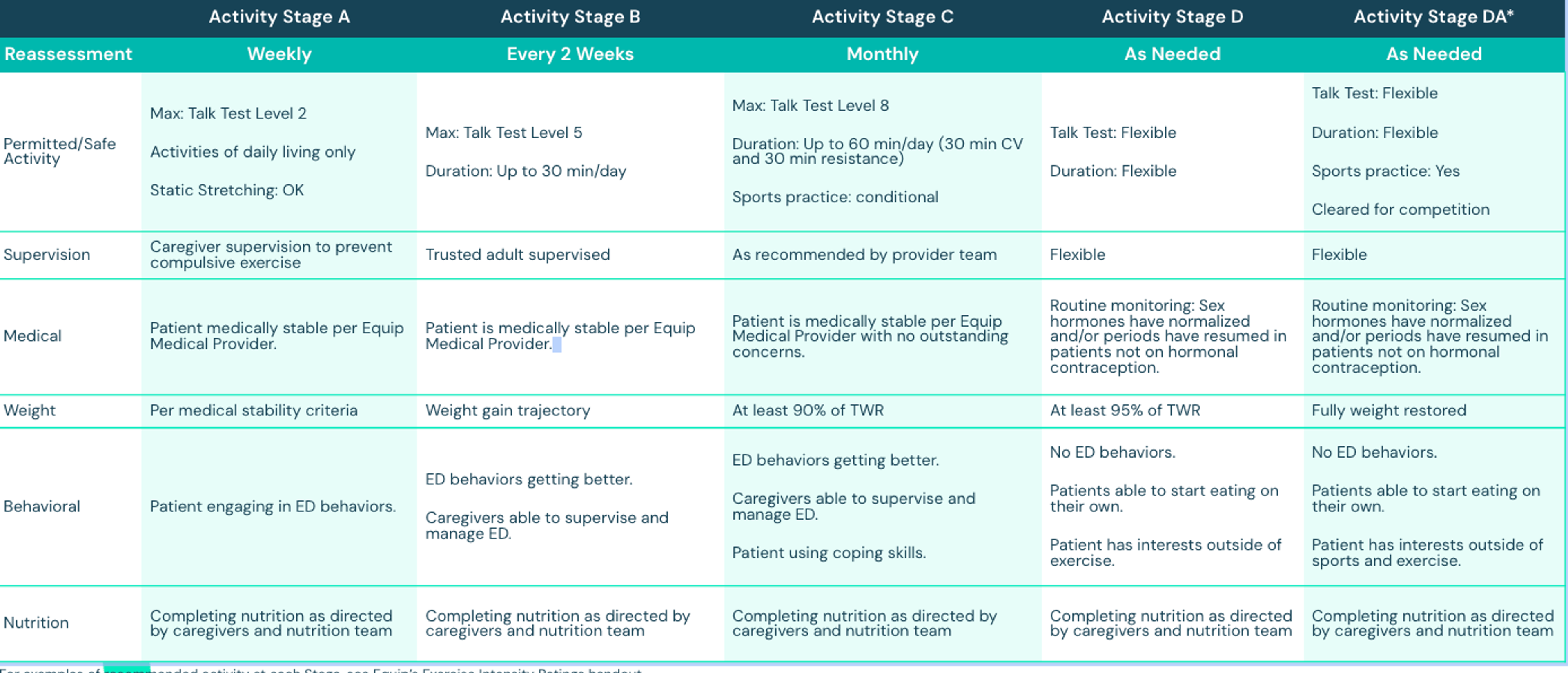

This brings us to Equip’s SAFER protocol, which stands for Safe Approach For Exercise Return. It is a staged approach which was developed in collaboration with the Safe Exercise at Every Stage (SEES) authors and adapted for family-based treatment as well as adult treatment at Equip.

Below is an at-a-glance look at Equip’s SAFER protocol.

In addition to our SAFER protocol, Equip also has a variety of athlete-specific resources:

- Athlete support groups (for supports and patients)

- Providers with expertise in eating disorders and sports medicine/psychology/nutrition

- Use of exercise-specific validated measures (CET)

- Peer/family mentors with lived experience

- Fully virtual (addressing geographic barriers, privacy concerns)

- Collaboration with athlete’s support system

For more information on treating athletes with eating disorders, watch my recorded Equip Academy presentation on the topic. You can also explore past Equip Academy presentations and register for upcoming events here.

- Chapa, D. A. N., Johnson, S. N., Richson, B. N., Bjorlie, K., Won, Y. Q., Nelson, S. V., Ayres, J., Jun, D., Forbush, K. T., Christensen, K. A., & Perko, V. L. (2022). Eating-disorder psychopathology in female athletes and non-athletes: A meta-analysis. The International journal of eating disorders, 55(7), 861–885. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23748

- Plateau, Carolyn R et al. “Female athlete experiences of seeking and receiving treatment for an eating disorder.” Eating disorders vol. 25,3 (2017): 273-277. doi:10.1080/10640266.2016.1269551

- Hazzard, V. M., Schaefer, L. M., Mankowski, A., Carson, T. L., Lipson, S. M., Fendrick, C., Crosby, R. D., & Sonneville, K. R. (2020). Development and Validation of the Eating Disorders Screen for Athletes (EDSA): A Brief Screening Tool for Male and Female Athletes. Psychology of sport and exercise, 50, 101745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101745

- Mountjoy, M., et al. (2023). 2023 International Olympic Committee's (IOC) consensus statement on Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs). British journal of sports medicine, 57(17), 1073–1097. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2023-106994