- Although atypical anorexia nervosa is officially a different diagnosis than the more well-known eating disorder anorexia nervosa, they are more alike than they are different.

- Anorexia is labeled “atypical” when weight is “normal” or even above what’s expected, but the condition includes all of anorexia’s other symptoms—and most/almost all of the same harms and risks to mental and physical health.

- Atypical anorexia sometimes goes undiagnosed due to people with the condition often presenting with “normal” weight—that’s why awareness is so crucial.

After being diagnosed with atypical anorexia, Nicky England, a peer mentor at Equip, struggled at first to get proper care for her eating disorder—because she didn’t fit the anorexia stereotype “I was warned by providers that it would be challenging to get insurance coverage for atypical anorexia,” she says. “I experienced providers treating me differently from other patients because I was in a larger body. Many of them reassured me that they weren’t going to let me gain weight, even though gaining weight ended up being a crucial aspect of my recovery.”

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is one of the most commonly known and most well-researched eating disorders. But most people only associate it with food restriction and low body weight, not realizing that AN can present in ways people might not expect. There are actually anorexia subtypes—including atypical anorexia, which doesn't look like the stereotype of anorexia nervosa from the outside.

“Atypical anorexia entails the same symptoms as anorexia, except someone who struggles with atypical anorexia is not classified as underweight,” says Hannah Bishop, LPC, an Equip Health eating disorder clinician with lived experience. “The term/diagnosis is problematic because it is using weight as an indicator of health and the seriousness of the illness. The term is suggesting that due to the size of someone’s body, the impact is less severe, and we know that isn’t true.”

Although the term includes the word “atypical,” the disorder may actually be even more prevalent than anorexia nervosa. And in reality, atypical anorexia nervosa presents the same or similar health risks as anorexia nervosa and impacts quality of life and overall health just as negatively. Unfortunately, a lack of awareness about atypical anorexia combined with diet culture and weight stigma can lead to people going undiagnosed or facing delays in care and treatment.

In this article, we explore types of anorexia, atypical anorexia nervosa, atypical anorexia diagnostic criteria, atypical anorexia symptoms, atypical anorexia recovery, and more.

What is atypical anorexia?

Let’s start out with understanding what anorexia nervosa is to help us better explain the specifics of atypical anorexia nervosa.

Eating disorders are known mental health conditions as outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Edition (DSM-5-TR), the guide that clinicians use to help diagnose eating disorders based on specific criteria.

The following criteria must be met for a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa:

- Restriction of food and drink: If someone doesn’t eat or drink enough, they’re going to have lower energy than what they need to support health, leading to substantially low body weight in the context of age, sex assigned at birth, and other factors.

- Intense fear of gaining weight: Even though people with anorexia can be underweight, diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa includes a fear of gaining weight or becoming fat—and/or the person engages in persistent behavior that interferes with weight gain.

- Disturbance in body image: People with anorexia nervosa may equate weight with self-worth, have a distorted sense of what their body looks like, and deny the seriousness of their low body weight.

Atypical anorexia nervosa is a separate eating disorder, but it shares most of the same criteria as anorexia nervosa. In the DSM-5, the disorder is listed under the category of “other specified feeding or eating disorder”(OSFED), formerly called “eating disorder not otherwise specified” (EDNOS).

“The symptoms of atypical anorexia are the same as anorexia nervosa,” Bishop explains. Those can include intense fear of weight gain, severe restriction of food intake, rapid weight loss, distorted body image, and can include compensatory behaviors. “The only difference is that the DSM-5 states that the individual is not underweight—in reference to using the BMI scale, which we know is also problematic.”

But when it comes to atypical anorexia nervosa, the DSM-5 doesn’t look at BMI or weight as a tool to diagnose. It does, however, explain that someone has atypical anorexia nervosa when all the diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa are met but their weight is still within the “normal”—or even higher than normal—range.

A bit more about BMI

BMI stands for body mass index, which is a calculation of weight relative to height. As Bishop notes, BMI can be a problematic assessment.

The DSM-5 doesn’t use a strict BMI cut-off, nor does it use BMI as diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa. However, it does use BMI to indicate severity after a diagnosis for adults.

So, even if you or a loved one is of “normal” or “above normal” weight, you or they could have atypical anorexia nervosa.

What are the signs and symptoms of atypical anorexia?

Now let’s get into the symptoms of atypical anorexia nervosa and compare them to anorexia nervosa. The tables below illustrate how similar the two eating disorders are. The main difference is that people with atypical anorexia don’t have a significantly low body weight.

Psychological and behavioral symptoms

By and large, the psychological impact of these two eating disorders are the same. Below is a list of symptoms that can be (but aren’t always) seen in both disorders.

| Psychological and behavioral symptoms | Anorexia nervosa | Atypical anorexia nervosa |

| Intense fear of gaining weight | √ | √ |

| Distorted body image/body dissatisfaction | √ | √ |

| Preoccupation with food, dieting, or calories | √ | √ |

| Low self-esteem linked to body shape/weight | √ | √ |

| Denial of the seriousness of low body weight | √ | √ |

| Anxiety or depression | √ | √ |

| Perfectionism | √ | √ |

| Obsessive thoughts or behaviors around eating | √ | √ |

| Social withdrawal due to body image concerns | √ | √ |

| Guilt or shame around eating | √ | √ |

Physical symptoms

Since some physical symptoms will only present when body weight is significantly low, a few of the physical symptoms of anorexia nervosa are less common in atypical anorexia nervosa. The appearance of lanugo, fine long body hair, is an example. Below is a list of symptoms that can appear (but don’t always) in those with each disorder.

| Physical symptom | Anorexia nervosa | Atypical anorexia nervosa |

| Significantly low body weight | √ | X |

| Noticeable weight loss | √ | √ |

| Fatigue/low energy | √ | √ |

| Dizziness or fainting | √ | √ |

| Cold intolerance | √ | √ |

| Lanugo (fine body hair) | √ | X (less common) |

| Bradycardia (slow heart rate) | √ | √ (may occur) |

| Hypotension (low blood pressure) | √ | √ (may occur) |

| Amenorrhea (loss of menstrual period) | √ | √ (may occur, less consistent) |

| Hair thinning/brittle nails | √ | √ |

| Gastrointestinal issues (constipation, bloating) | √ | √ |

| Cold, mottled hands or feet | √ | √ |

Medical red flags requiring immediate attention

For both eating disorders, sometimes immediate medical attention is required to protect your safety or the safety of a loved one. As you can see, the red flags are the same for both eating conditions.

| Medical red flags | Anorexia nervosa | Atypical anorexia nervosa |

| Heart rate <40 bpm | √ | √ |

| Blood pressure < 90/60 mmHg | √ | √ |

| Body temperature < 95.9 °F (35.5 °C) | √ | √ |

| Electrolyte abnormalities (e.g., low potassium) | √ | √ |

| Severe dehydration | √ | √ |

| Syncope (fainting) or presyncope (feeling faint) | √ | √ |

| Hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) | √ | √ |

| Severe bradycardia or arrhythmias | √ | √ |

| Marked orthostatic hypotension (drop in blood pressure upon standing, leading to dizziness/fainting) | √ | √ |

| Suicidal ideation or severe psychiatric distress | √ | √ |

| Rapid weight loss | √ | √ |

Why is the term “atypical anorexia” misleading (and potentially harmful)?

Again, the major difference between atypical anorexia nervosa and anorexia nervosa has to do with weight status, but this can be a problematic distinction.

For example, with atypical anorexia nervosa, you or a loved one may be of a relatively “normal” or even a higher weight based on age, sex assigned at birth, and height. But you or a loved one may still meet much of the criteria for having anorexia nervosa and face the same serious health risks. At the same time, you, a caregiver, or even a healthcare provider may deem you “not sick enough” to warrant treatment.

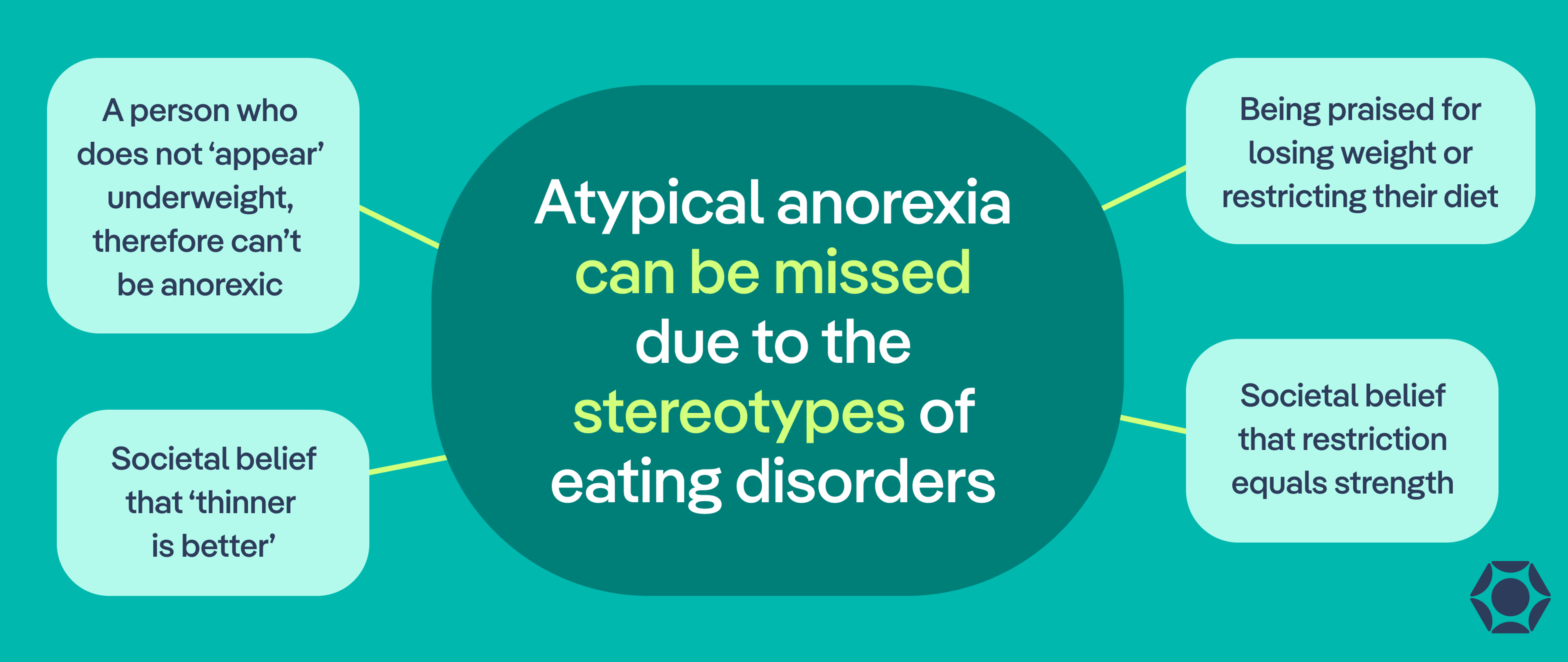

“Atypical anorexia can be missed due to the stereotype of eating disorders,” Bishop says. “When society and even medical providers hear about eating disorders, they often think of a severely underweight Caucasian female. However, we know that eating disorders impact various genders, races, and people of all body sizes. In addition, a person who does not ‘appear’ underweight may be praised for losing weight or restricting their diet due to the societal belief that ‘thinner is better’ or restriction equals strength.”

What causes atypical anorexia?

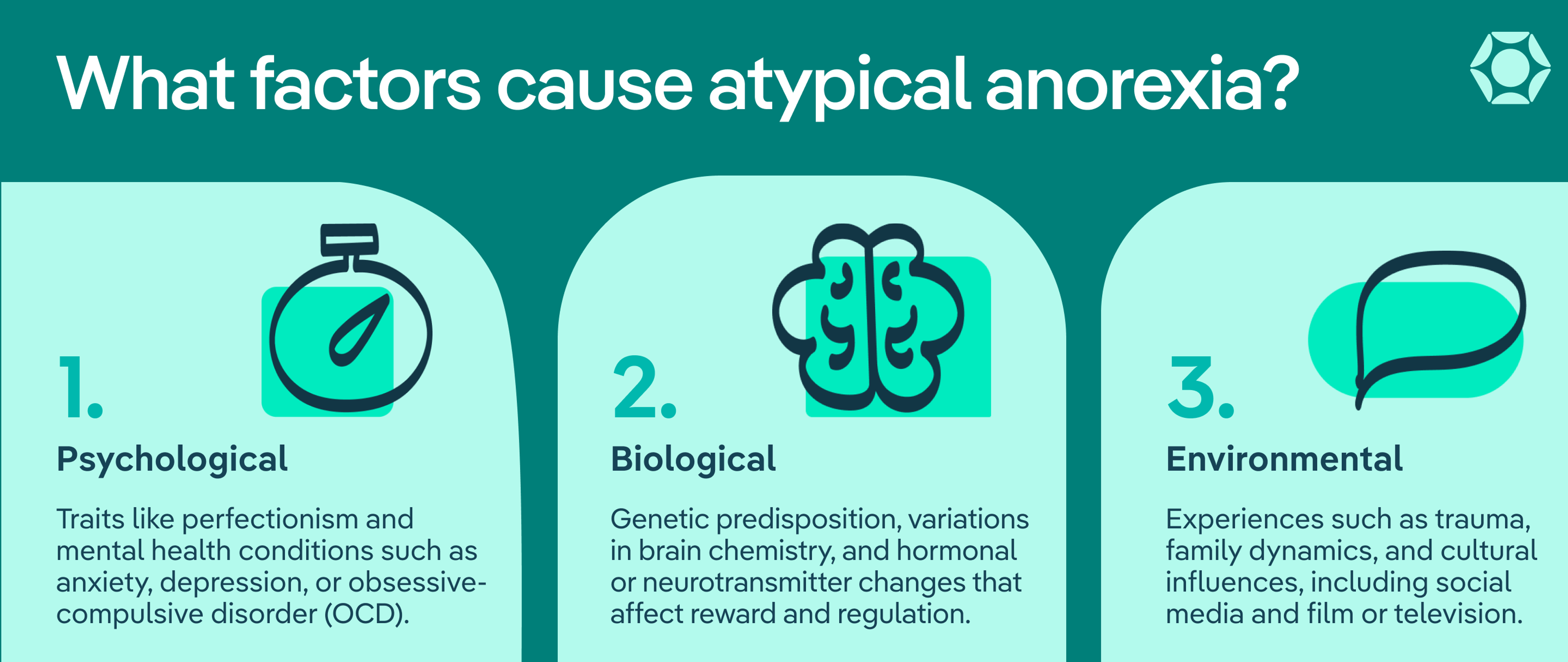

“Eating disorders, including atypical anorexia, are not caused by one underlying issue,” Bishop says. “We know that eating disorders occur as a result of a combination of psychological, biological, and environmental factors.”

There are many factors that contribute to someone developing atypical anorexia. These factors can include:

- Psychological: Psychological factors might include traits such as perfectionism and underlying mental health conditions, including anxiety, depression, or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

- Biological: Biological factors might include a genetic risk or predisposition, brain changes, differences in neurotransmitters and hormones that impact reward centers in the brain, and more.

- Environmental: Environmental factors might include a history of trauma, complex family dynamics, and even cultural influences, such as from social media or film and television.

These factors tend to be somewhat unique, meaning that the specific factors affecting you or a loved one may be different from those of someone else with the diagnosis.

How is atypical anorexia diagnosed?

Atypical anorexia nervosa is diagnosed much in the same way as anorexia nervosa. A clinician will evaluate physical and behavioral symptoms, weight status, nutritional status, and whether you’ve lost a significant amount of weight. They will work with you to rule out other possible mental or physical health conditions that could be the cause of symptoms. Along with their assessment, they will investigate whether symptoms align with the criteria outlined in the DSM-5. It’s important to work with an eating disorder-informed and Health at Every Size (HAES)-aligned clinician to ensure you won’t be dismissed or given harmful advice.

Atypical anorexia treatment

If a clinician determines you or your loved one do show symptoms of anorexia nervosa or atypical anorexia nervosa, they’ll formulate a treatment plan.

“Treatment at Equip includes a five-person treatment team: a therapist, dietician, medical team member, peer mentor and family mentor,” Bishop says. “We utilize different modalities dependent upon the age of the patient. Treatment at Equip lasts for one year, and time can be extended, if necessary, or a referral can be placed for an outside provider at that time.”

The bottom line

Atypical anorexia nervosa is currently considered a separate eating disorder from anorexia nervosa, but the criteria and symptoms are largely the same between the two, with the exception of weight. While people with anorexia nervosa have a substantially low weight, those with atypical anorexia nervosa tend to be of “normal weight” or even above that. But the “atypical” label can often be more harmful than helpful. At Equip, clinicians and other staff consider it all "anorexia" and treat both diagnoses with the same evidence-based, personalized approach.

Atypical anorexia nervosa is as common as, if not more common, than anorexia nervosa. Yet, it often goes undiagnosed. Because of the weight distinction, it can fly under the radar, despite it being just as serious to health.

If you’re experiencing symptoms consistent with atypical anorexia, know that you need and deserve help. Schedule a call with Equip to talk through your concerns and whether our virtual treatment is right for you.

FAQ

What qualifies as atypical anorexia?

Atypical anorexia nervosa is currently considered a separate eating disorder from anorexia nervosa. However, the symptoms are largely the same, with the exception of weight status. While people with anorexia nervosa have a substantially low weight, people with atypical anorexia nervosa are of “normal” or “above normal” weight.

What is the controversy with atypical anorexia?

The controversy surrounding atypical anorexia nervosa has to do with the diagnostic criteria regarding weight. People with anorexia nervosa have a substantially low weight for their age, sex assigned at birth, height, and other factors. People who meet all other criteria for anorexia nervosa but are of “normal” or “above normal” weight have atypical anorexia. With weight factoring into the picture, and with less awareness surrounding atypical anorexia, the condition often goes undiagnosed, putting people at risk for serious health issues.

Are there different types of anorexia?

The two types of anorexia are anorexia nervosa and atypical anorexia nervosa. These are two separate but related eating disorders. They share the same basic criteria for diagnosis. However, People who meet all other criteria for anorexia nervosa but are of “normal” or “above normal” weight have atypical anorexia. Additionally, anorexia nervosa has two subtypes: the restricting type and the binge eating/purging type.

Can you have anorexia without being underweight?

Yes, you can have what’s called atypical anorexia nervosa. This is a separate eating disorder that shares most of the criteria for diagnosis as anorexia nervosa. However, people with atypical anorexia are not underweight.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth Edition, American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

“Atypical Anorexia | Symptoms, Treatment & Support | NEDA.” National Eating Disorders Association. Accessed 18 Dec. 2025.

Backholm, Klas, et al. “The Prevalence and Impact of Trauma History in Eating Disorder Patients.” European Journal of Psychotraumatology, vol. 4, Nov. 2013.

Baker, Jessica H., et al. “Genetics of Anorexia Nervosa.” Current Psychiatry Reports, vol. 19, no. 11, Sept. 2017, p. 84. PubMed.

Balasundaram, Palanikumar, and Prathipa Santhanam. “Eating Disorders.” StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, 2025. PubMed.

Bray, George A. “Beyond BMI.” Nutrients, vol. 15, no. 10, May 2023, p. 2254. PubMed.

Erriu, Michela, et al. “The Role of Family Relationships in Eating Disorders in Adolescents: A Narrative Review.” Behavioral Sciences, vol. 10, no. 4, Apr. 2020, p. 71.

Gaiaschi, Ludovica, et al. “New Perspectives on the Role of Biological Factors in Anorexia Nervosa: Brain Volume Reduction or Oxidative Stress, Which Came First?” Neurobiology of Disease, vol. 199, Sept. 2024, p. 106580. PubMed.

Garber, Andrea K., et al. “Weight Loss and Illness Severity in Adolescents With Atypical Anorexia Nervosa.” Pediatrics, vol. 144, no. 6, Dec. 2019, p. e20192339.

Himmerich, Hubertus, and Janet Treasure. “Anorexia Nervosa: Diagnostic, Therapeutic, and Risk Biomarkers in Clinical Practice.” Trends in Molecular Medicine, Special issue: Eating disorders, vol. 30, no. 4, Apr. 2024, pp. 350–60. ScienceDirect.

Holland, Lauren A., et al. “Psychological Factors Predict Eating Disorder Onset and Maintenance at 10-Year Follow-Up.” European Eating Disorders Review : The Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, vol. 21, no. 5, July 2013, p. 405.

Momen, Natalie C., et al. “Comorbidity Between Eating Disorders and Psychiatric Disorders.” The International Journal of Eating Disorders, vol. 55, no. 4, Jan. 2022, p. 505.

Skowron, Kamil, et al. “Backstage of Eating Disorder—About the Biological Mechanisms behind the Symptoms of Anorexia Nervosa.” Nutrients, vol. 12, no. 9, Aug. 2020, p. 2604.

Suhag, Khushi, and Shyambabu Rauniyar. “Social Media Effects Regarding Eating Disorders and Body Image in Young Adolescents.” Cureus, vol. 16, no. 4, Apr. 2024, p. e58674. PubMed.