Many people associate anorexia with being extremely thin and restricting food. And while those two things are often characteristics of anorexia, it’s not so black and white: for one thing, people with anorexia aren’t always underweight, and for another, anorexia can also involve episodes of binge eating and purging. When the latter occurs, it’s known as anorexia binge-purge subtype (AN-BP). Though it’s less commonly known, anorexia binge-purge subtype is just as dangerous as anorexia that’s purely restrictive. It can negatively affect physical and mental health, leading to issues such as heart attack, osteoporosis, anxiety, and depression, among others.

Understanding anorexia and binge-purge can help you identify if you or a loved one may have this condition. Read on to learn about this lesser known (but equally serious) form of anorexia, including its prevalence, symptoms, and effective treatments for binge-purge anorexia.

What is anorexia binge-purge subtype?

People with anorexia nervosa binge-purge subtype exhibit three main behaviors:

- Food restriction

- Binge eating

- Purging

Let’s break this down: Like people with anorexia nervosa restrictive type (the commonly known version of anorexia), people with AN-BP severely limit their food, both in terms of intake and variety. In fact, people with AN-BP may engage in more frequent restrictive eating behaviors compared to people with restrictive anorexia.

Where the two differ is that those with AN-BP can also experience episodes of binge eating and purging. This is when someone eats large quantities of food in a short amount of time and then “gets rid of” the food they consumed through purging behaviors like vomiting, excessive exercise, or laxative use.

“A person with AN-BP can feel a loss of control when eating or react to a meal by engaging in some kind of purging behavior afterward,” explains Angela Celio Doyle, PhD, Equip’s VP of Behavioral Health Care.

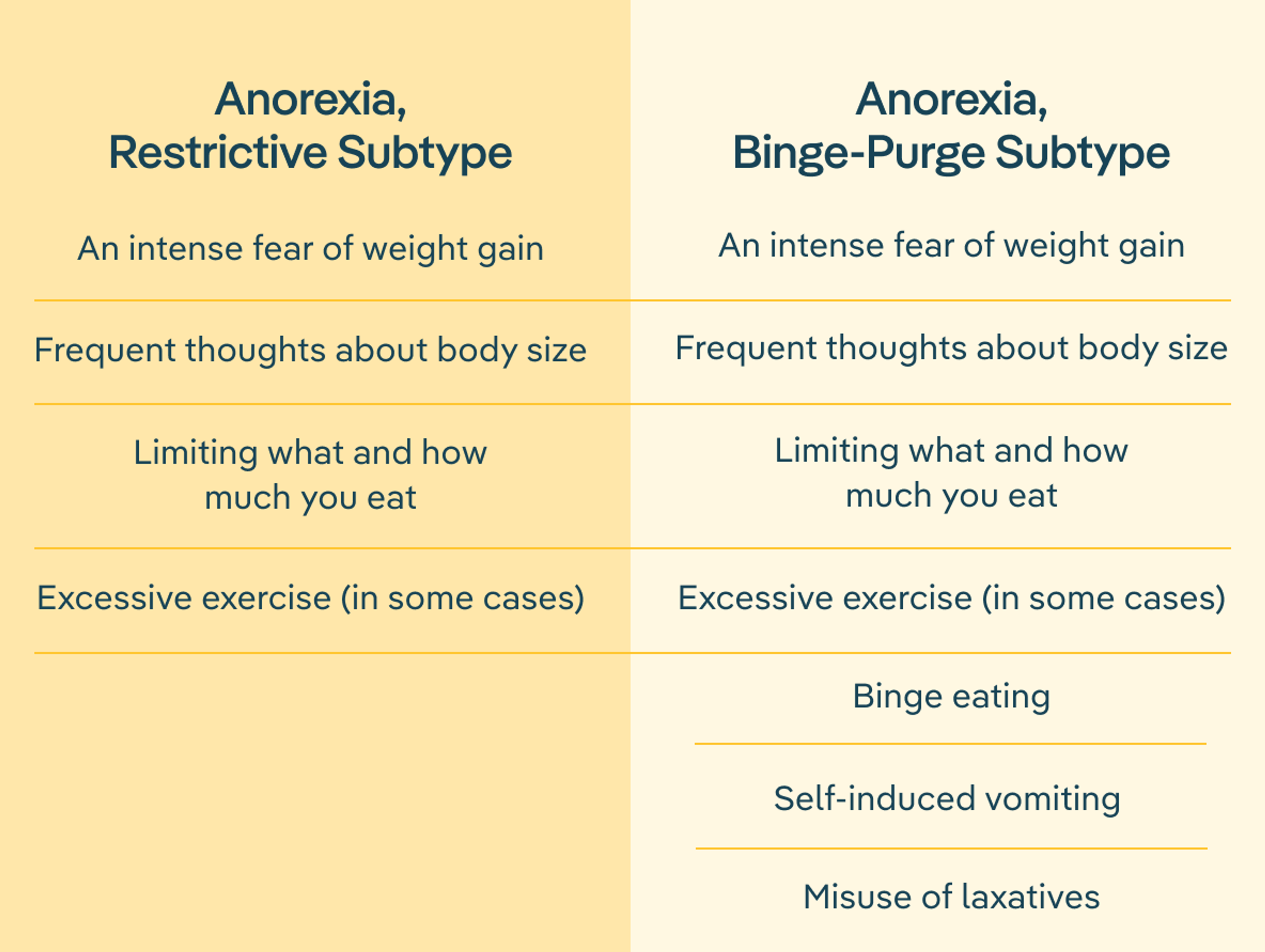

The chart below outlines how restrictive anorexia and binge-purge anorexia behaviors compare.

How is anorexia binge-purge subtype diagnosed?

To be clinically diagnosed with AN-BP, patients must engage in these three behaviors—restrictive eating, binge eating, and purging—consistently for at least three months.

But it’s important to note that most eating disorders don’t fit neatly into one diagnostic box, at least not forever. As Doyle puts it, “although eating disorders can appear very different, at their core they’re very similar in terms of what drives them, and so diagnoses can often overlap or change over time,” Doyle says. “Restrictive anorexia may develop into AN-BP without treatment. Likewise, AN-BP can evolve into bulimia.” So it’s not uncommon to be diagnosed with restrictive anorexia and then eventually start to binge and purge. See more about anorexia vs bulimia to understand the difference.

How common is anorexia binge-purge subtype?

It’s difficult to pinpoint the exact prevalence of anorexia binge-purge. Generally speaking, up to 4% of females and 0.3% of males experience anorexia nervosa over the course of their lifetime. Of those patients diagnosed with anorexia, 30 to 50% have anorexia binge-purge subtype.

Statistics, however, don’t tell the full story of the severity and detrimental impact of AN-BP. “Even though these rates seem low at a glance, they still represent millions of people who are struggling with a very serious eating disorder,” Doyle says.

What are the symptoms of anorexia binge-purge subtype?

AN-BP is unique in that patients with this condition experience symptoms from several different eating disorder diagnoses at once. “The most common eating disorder symptoms co-occur with each other in anorexia binge-purge subtype,” says Doyle. “A person with AN-BP has at least two, but sometimes all three, cardinal eating disorder behaviors: dietary restriction, binge eating, and purging.”

What makes AN-BP different from other eating disorders with similar symptoms, like binge eating disorder and bulimia, has less to do with behaviors than with the psychology of the illness. Typically, a patient receives an AN-BP diagnosis when their symptoms and mindset more closely meet the criteria for anorexia nervosa, even if they also exhibit the binge eating and purging behaviors characteristics of binge eating disorder or bulimia.

Below is a breakdown of the most common symptoms of binge-purge anorexia.

Behavioral symptoms

- Restrictive eating

- Binge eating (consuming a lot of food quickly with a feeling of being out of control)

- Self-induced vomiting

- Misuse of laxatives or diuretics

- Excessive exercise in order to “make up” for meals

- Withdrawal from social activities

Psychological symptoms

- An intense fear of weight gain

- A distorted perception of weight or body shape

- An overemphasis of the importance of weight or body shape

- Preoccupation with food

- Anxiety

- Depression

Physical symptoms

- Damage to teeth

- Constipation or other digestive problems

- Fatigue or weakness

- Dehydration

- Electrolyte imbalance (particularly low potassium levels)

- Slower than normal heart rate

- Edema (swelling)

The role of the binge-restrict cycle

Most people with AN-BP experience something known as the binge-restrict cycle, where a period of restriction leads to episodes of binge eating, which then triggers feelings of shame, in turn resulting in the desire to restrict again (or purge).

This cycle is the body’s natural response to limiting food intake. “Restriction—even when it’s just eliminating one food group—takes us out of our body’s biological comfort zone,” Doyle explains. “Our bodies know that we need consistent, well-rounded nutrition, and it fights back with urges to binge.”

Because of that hard-wired survival mechanism, Doyle says that restricting food generally or certain foods specifically (unless medically necessary) is usually an unsafe and unhealthy tactic. “There are a lot of restrictive patterns that have been co-opted into the diet culture space that can do more harm than good,” she says. “This includes intermittent fasting, cleanses, elimination diets, and carb cycling.”

Differences from other eating disorders

Other eating disorders also involve parts of the binge-restrict cycle. But only anorexia nervosa binge-purge consistently involves all three aspects: restriction, binge eating, and purging.

- People with binge eating disorder eat a large amount of food in a short period of time, but they don’t purge.

- People with purging disorder “get rid” of food by making themselves vomit, over-exercising or using laxatives, but they don’t binge eat.

- People with bulimia nervosa binge and then purge to compensate for the calories they consumed during their binge.

- People with restrictive anorexia limit what they eat, but they don’t binge and purge.

What does treatment for anorexia binge-purge subtype look like?

As with all eating disorders, implementing swift, evidence-based treatment is the key to long-term recovery of AN-BP. Anorexia binge-purge subtype is a serious mental health condition that can do significant harm to your mental and physical health when left untreated. People struggling with AN-BP may experience complications such as:

- Electrolyte imbalances, which can lead to heart attack or stroke

- Irregular heart beat

- Heart failure

- Osteopenia and osteoporosis

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Suicidal thoughts

Research also indicates that those with anorexia binge-purge subtype are more likely to drop out of treatment compared to people with other eating disorders, which makes it even more important to intervene quickly, before the eating disorder has time to dig deep roots. Recovery is possible for everyone with AN-BP, regardless of how long they’ve been struggling, but getting treatment as soon as possible can reduce the health risks and also improve recovery outcomes.

The most common and effective treatment for binge-purge anorexia is enhanced cognitive behavioral therapy. It’s also important for patients to work with a multidisciplinary care team—which should include a dietitian, therapist, and medical provider—who can support all aspects of their health.

Enhanced cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT-E)

“Enhanced cognitive behavioral therapy (also known as CBT-E) is a specific version of cognitive behavioral therapy specifically for eating disorders,” Doyle says. “It’s the first treatment recommended to patients with AN-BP because of its strong evidence for helping the most people.”

Considered one of the most effective treatments for eating disorders, CBT-E can be used to treat a variety of diagnoses through a highly individualized plan that helps patients to:

- Stop binge and purge behaviors

- Re-establish regular eating habits

- Confront their distorted perceptions

- Address their disordered thoughts and behaviors

“Stopping binge and purge behaviors can be a huge relief for someone struggling with AN-BP,” Doyle says. “CBT-E also focuses on the thoughts and feelings that drive the eating disorder behaviors so that the person can experience a life that is more and more symptom-free over time.”

Multidisciplinary treatment approaches

Like eating disorders themselves, each person struggling with disordered thoughts and behaviors is unique. While treatment approaches vary from person to person, experts agree that a multidisciplinary team, as well as social support, gives patients the best chances of achieving long-term recovery.

“At Equip, we offer CBT-E, and our patients work with a team that includes a therapist, a dietitian, medical support, and mentorship by people who have lived experience with an eating disorder,” Doyle explains. “Mentorship from someone who has been through something similar, especially for patients with lesser-known conditions like anorexia binge-purge, can provide a lot of much-needed hope.”

Guide: Breaking the Binge-Restrict CycleThe Equip takeaway: understanding and healing AN-BP

The anorexia binge-purge subtype is a type of anorexia in which a person engages in episodes of binge eating and purging as well as restricting their food intake. AN-BP can lead to serious health complications ranging from digestive problems and damage to teeth to heart problems and weak bones.

Long-term recovery from eating disorders, including anorexia nervosa binge-purge, is possible, but it requires evidence-based treatment. Therapy, especially CBT-E, has been shown to be an effective treatment for AN-BP, especially when delivered while a patient works with a multidisciplinary care team.

If you’re concerned that you or a loved one may have AN-BP, seek help now. This harmful eating disorder is fully curable—but it doesn’t go away on its own. Talk to your doctor or a mental health provider about your concerns, or schedule a call with an Equip team member.

FAQs

What are the main symptoms of the anorexia binge-purge subtype?

The main binge-purge anorexia symptoms are food restriction, binge eating (eating large quantities of food in a short amount of time) and purging (“getting rid of” the food they consumed through behaviors like vomiting, excessive exercise, or laxative use). To be clinically diagnosed with AN-BP, someone needs to exhibit these behaviors consistently for at least three months.

How common is the anorexia binge-purge subtype compared to other eating disorders?

The exact prevalence of anorexia binge-purge is hard to nail down. Generally speaking, up to 4% of females and 0.3% of males experience anorexia nervosa over the course of their lifetime. Of those patients diagnosed with anorexia, 30 to 50% have anorexia binge-purge subtype. This means millions of people struggle with AN-BP.

What is the binge-restrict cycle and how does it affect those with anorexia binge-purge?

The binge-restrict cycle is a pattern where a period of food restriction is followed by episodes of binge eating, which then triggers feelings of shame, in turn resulting in the desire to restrict again. People with anorexia binge-purge subtype engage in the binge-restrict cycle, but may also purge after a binge. This differs from those with other eating disorders, who typically only engage in one or two parts of these three behaviors. For example, people with the restrictive subtype of anorexia nervosa only restrict, those with binge eating disorder only binge, and those with bulimia binge and purge.

What treatment options are available for someone with the anorexia binge-purge subtype?

Enhanced cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT-E) is one of the most effective treatments for binge-purge anorexia. This type of therapy focuses on stopping binge and purge behaviors, re-establishing regular eating habits, and addressing distorted thoughts. Working with a dietitian, medical provider, and mentor—in addition to a CBT-E-trained therapist—can further help someone with AN-BP.

How can families support a loved one with the anorexia binge-purge subtype?

If someone you love is struggling with the anorexia binge-purge subtype, you can support them by learning about this eating disorder, encouraging open communication, and examining your own beliefs and feelings about food and eating. You can also encourage your loved one to find support, and help them find the providers and resources they need to get better.

What are the long-term health risks of the anorexia binge-purge subtype?

The long-term health risks of the anorexia binge-purge subtype are serious. They include electrolyte imbalances (which can lead to heart attack or stroke), osteoporosis, suicidal thoughts, irregular heart beat, and heart failure, among many others.

- Attia, Evelyn and Walsh, B Timothy. “Anorexia Nervosa.” MSD Manual Professional Version. Revised July 2022. https://www.msdmanuals.com/en-gb/professional/psychiatric-disorders/eating-disorders/anorexia-nervosa

- Eeden, Annelies E. van, Daphne van Hoeken, et al.. “Incidence, Prevalence and Mortality of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa.” Current Opinion in Psychiatry. vol. 34, 6 (2021): 515–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/yco.0000000000000739.

- “Eating Disorders.” National Institute of Mental Health. n.d. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders

- Peat, Christine, James E. Mitchell, et al. “Validity and Utility of Subtyping Anorexia Nervosa.” Edited by B. Timothy Walsh. International Journal of Eating Disorders. vol. 42, 7 (2009): 590–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20717.

- Puckett, Leah. “Renal and Electrolyte Complications in Eating Disorders: A Comprehensive Review.” Journal of Eating Disorders. vol. 11, 1 (2023): 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00751-w

- Reas, Deborah Lynn and Rø, Øyvind. “Less Symptomatic, But Equally Impaired: Clinical Impairment in Restricting Versus Binge-Eating/Purging Subtype of Anorexia Nervosa.” Eating Behaviors. vol. 28 (2018): 32-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2017.12.004

- Robinson, Lauren et al. “Eating Disorders and Bone Metabolism in Women.” Current Opinion in Pediatrics. vol. 29, 4 (2017): 488–496. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000508

- Rylander, Melanie et al. “A Comparison of the Metabolic Complications and Hospital Course of Severe Anorexia Nervosa by Binge-Purge and Restricting Subtypes.” Eating Disorders: The Journal of Treatment & Prevention. vol. 25, 4 (2017): 345-357. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2016.1269555

- Serra, Riccardo, Chiara Di Nicolantonio, et al. “The Transition from Restrictive Anorexia Nervosa to Binging and Purging: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity. vol. 27 (2021): 857-865. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-021-01226-0.

- Smith, Sarah and Woodside, D Blake. “Characterizing Treatment-Resistant Anorexia Nervosa.” Frontiers in Psychiatry. vol. 11 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.542206

- Vall, Eva and Wade, Tracey D. “Predictors of Treatment Outcome in Individuals With Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” International Journal of Eating Disorders. vol. 48, 7 (2015): 946-971. doi:10.1002/eat.22411