- Diets and eating disorders both involve changes to food habits, but they are not the same thing. Dieting for weight loss is an unfortunately common behavior, whereas eating disorders are mental illnesses that affect less than 9% of the population.

- Dieting can sometimes be a slippery slope to an eating disorder, as it involves disordered behaviors, and food restriction can “turn on” an eating disorder in someone who is at risk.

- Dieting is a choice, doesn’t take over a person’s mind, and has a definite end point. An eating disorder is not a choice, takes over most of a person’s brain space, and will last indefinitely until treated.

- If you’re worried that your diet or the diet of a loved one is becoming disordered, it’s important to get professional support. Equip can help you assess your risk and determine next steps.

One of the telltale signs of an eating disorder is a change in someone’s eating habits. But changing your eating habits is also the defining characteristic of going on a diet—so when does dieting become an eating disorder? The answer is nuanced, especially because the worlds of dieting, disordered eating, and eating disorders have a fair amount of overlap. Read on to learn the difference between a diet vs. an eating disorder, whether dieting can become an eating disorder, and when to be concerned.

Dieting and eating disorder: the basics

Before we break down when dieting becomes an eating disorder, let’s define the terms. While the word “diet” can refer simply to what a person eats, here we’re talking specifically about weight loss diets. In this context, a diet can be defined as an eating plan in which someone eats less food, or only particular types of food, in order to become thinner or lose weight. People go on weight loss diets for a variety of reasons, including because they think it will improve their health or “wellness,” or simply because they want to look a certain way.

Eating disorders, on the other hand, are mental illnesses characterized by severe and persistent disturbances in eating behaviors, accompanied by distressing thoughts and emotions. Eating disorders are disabling and deadly disorders that have serious consequences on physical, psychological, and emotional health and disrupt a person’s ability to go about their life. There are several different types of eating disorders, including:

- Anorexia

- Bulimia

- Binge eating disorder (BED)

- Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID)

- Other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED)

Unfortunately, dieting is extremely common. According to research, about 17.1% of American adults are on a diet on any given day, and half of adult Americans (about 130 million people) attempted to lose weight within the past year. Eating disorders, on the other hand, are less prevalent: about 9% of Americans will have an eating disorder at some point in their lifetime, and about 5.5 million will develop one this year.

So while dieting and eating disorders have similarities—both involve changes in food habits and a focus on making one’s body smaller—clearly not everyone on a diet has an eating disorder. Let’s take a look at the differences.

Diets vs. eating disorders

Telling the difference between a diet and an eating disorder can be tricky, especially in the context of diet culture, which tends to praise and normalize disordered behaviors, like fasting or cutting out entire food groups. However, there are specific things you can look for that can signal it’s not “just” a diet.

Some of the primary differences between a diet vs. an eating disorder include:

- How long it lasts: Generally, people go on diets for a finite amount of time. Someone may go on a diet ahead of an event (like a vacation or a wedding, for instance), or in order to reach a certain weight, and then go back to more normal eating afterward. Eating disorders have no natural end; people will continue to engage in their disordered behaviors until they get treatment.

- How it impacts other areas of a person’s life: “Dieting becomes an eating disorder when it’s associated with significant impairment in physical, emotional, occupational, or social domains,” explains Cara Bohon, PhD, an eating disorder researcher and associate professor at Stanford. Eating disorders can hurt relationships, negatively affect performance at school or work, and make it impossible to keep up with daily responsibilities.

- How much mental real estate it occupies: “A shift in thought patterns is one of the first red flags I often see,” says Christina Fattore, RD, an eating disorder dietitian. When compulsive thoughts about food, exercise, or body size and shape (sometimes called “food noise”) begin to take up most of a person's brain space, it’s time to be concerned.

- How important it is: Diets are pretty straightforward: they’re about following food rules and achieving a certain weight, and there is no deeper meaning. Eating disorders may look similar on the surface, but they become about much, much more. For someone with an eating disorder, there are extremely high stakes attached to the rules of their disease. If they “slip up” or ignore their eating disorder voice, they feel intense distress.

- Whether or not it feels like a choice: In general, going on a diet is a choice someone makes, and they can choose to stop when it no longer serves them. An eating disorder is not a choice, and someone can’t just decide to stop having an eating disorder. “Dieting has solidified its place in our society as a desirable lifestyle choice. However, I think it’s important to remember a diet is just that: a choice,” says Fattore. “With an eating disorder, the disorder itself is in the driver’s seat, not the other way around.”

These differences help to illustrate the different ways that diets and eating disorders affect a person, but they can be difficult to quantify or even to see at all, especially if you’re concerned about a loved one. Below are some more easily identifiable red flags:

- An extreme rigidity around food rules. “Eating disorders don’t make space for ‘cheat meals’ or ‘days off,” explains Fattore.

- Preoccupation with body size or shape. This might look like body checking, frequently weighing oneself, or comparing one’s body with other people’s bodies.

- A fixation on calorie counts and nutrition labels. This can also show up in behaviors like measuring and weighing food, and a need to be extremely precise about the quantities or kinds of food eaten.

- Mood shifts associated with insufficient nourishment. “Think about the term ‘hangry,’” says Bohon.

- Physical ailments that appear to be related to a person’s restrictive eating. This could include fatigue, hair loss, brittle nails, always being cold, or getting sick frequently.

- Social withdrawal. People with eating disorders tend to avoid plans that involve food, or turn down invitations in order to exercise. “Dodging situations that would require one to practice food flexibility is an indication that we’re veering into dangerous territory,” says Fattore.

- Other disordered weight loss behaviors in addition to the diet. This could include self-induced vomiting or misuse of laxatives.

If these signs resonate with you, taking our interactive eating disorder screener could be a helpful next step.

When does dieting become an eating disorder?

While diets and eating disorders are decidedly different from one another, one can lead to the other. This doesn’t mean that diets cause eating disorders (otherwise, everyone on a diet would develop an eating disorder, and that’s not what we see), but it does increase risk.

“For many years, it has been consistently shown in research that dieting is a risk factor for the development of eating disorders,” says Bohon. She cites research from the early 2000s that found that attempts to restrict eating were “robust predictors” of the onset of eating disorders, findings that were replicated over the following decades. More recent studies have found that the following diet-related behaviors all increase eating disorder symptoms:

Research has also shown that teenage dieting is what usually precedes the onset of bulimia and anorexia, and prospective studies have found that dieting increases the risk of developing an eating disorder by five.

Bohon does point out that some researchers suggest that dieting for weight loss doesn’t increase eating disorder risk, citing evidence that weight loss programs result in reductions of eating disorder symptoms. But there are flaws in making this conclusion, she says. “This interpretation of the evidence is short-sighted. As eating is controlled via dieting, concerns about shape or weight or eating are tempered. But when the dieting stops, the concerns elevate. Given that most weight loss efforts fail—weight is either not lost or regained the following year—any reductions in eating disorder symptoms would be expected to be temporary.”

Think of these seemingly conflicting data points this way: for some people, dieting itself can be a trigger for an eating disorder—likely because a negative energy balance, or eating fewer calories than you burn, can trigger an eating disorder in people predisposed to developing one. For others, dieting might appear to lessen disordered thoughts or behaviors, but that relief is short-lived: the relief comes from the fact that a person’s body more closely matches society’s thin ideal, and when the weight inevitably comes back, so do the disordered behaviors.

It’s also worth calling out that even for people who won’t go on to develop an eating disorder, dieting can have negative consequences. Studies have found that dieting can lead to:

- Nutritional deficiencies

- Menstrual irregularity

- Osteopenia and osteoporosis

- Stunted growth in kids and teens

- Irritability

- Fatigue

- Distractibility

- Binge eating

As one team of researchers put it, “our results showed that dieting may carry more risks than benefits as a means to lose weight.”

Can I ever go on a diet if I’m in recovery?

While every person is unique, most eating disorder experts would advise against going on a diet while in eating disorder recovery. There are, of course, some particular instances in which specific dietary modifications are medically necessary and may be considered healthy. For example, those with conditions like celiac disease or dairy allergies may need to adhere to specific diets that restrict certain foods. While these diets are limiting, they are distinct from weight loss diets because they provide sufficient nutrition and don’t promote explicit weight loss or an energy deficit. In these very specific cases, following a particular diet may be essential for managing a health condition.

All that said, weight loss diets are not recommended for people in recovery from an eating disorder. Research has consistently identified dieting as one of the strongest predictors and a significant risk factor for the development of an eating disorder. This slippery slope from a diet to an eating disorder is often the result of the “diet cycle,” or the “binge-restrict cycle,” which starts with restrictive eating, which leads to physical and psychological deprivation. These feelings of deprivation then cause the person to break their diet rules by overeating or bingeing, which typically results in guilt, body dissatisfaction—and the return to dieting. Dieting can also cause a negative energy balance, which can trigger an eating disorder relapse.

Perhaps more importantly, weight loss diets put diet culture’s values above a person’s true values or health. Not only is weight loss or thinness not a universal sign of health or morality, but dieting is often ineffective at best, and dangerous at worst. Research has consistently shown that most dieters regain the weight they lose, and that diets themselves often promote the adoption of disordered eating behaviors. Rather than fixating on weight, experts agree that it’s more important to prioritize behaviors that are truly health-promoting, like stress management, adequate sleep, joyful movement, and more.

Is dieting inherently bad?

Ultimately, it’s up to each individual person to decide what food choices work best for them. For people with celiac disease, that means cutting out gluten; for those who are lactose intolerant, that means eliminating dairy; others might simply find that they feel better when they eat certain foods rather than others. In all of these cases, a person’s chosen diet wouldn’t be considered disordered.

But when it comes to diets designed specifically for weight loss, it’s a different story. As the research shows, dieting for weight loss purposes is rarely sustainable and increases your risk of developing an eating disorder, making it a lose-lose endeavor.

Fattore sums it up like this: “If ‘going on a diet’ means incorporating a higher volume of nutrient-dense foods, exercising in a way that’s mentally and physically rewarding, and engaging with food in a more mindful manner, then sure, dieting can be healthy,” she says. “But if a diet means depriving your body of necessary calories, cutting out entire food groups, or ignoring physical cues like hunger or exhaustion, then I don’t think we can ever truly classify dieting as healthy.”

FAQ

What’s the difference between a diet and an eating disorder?

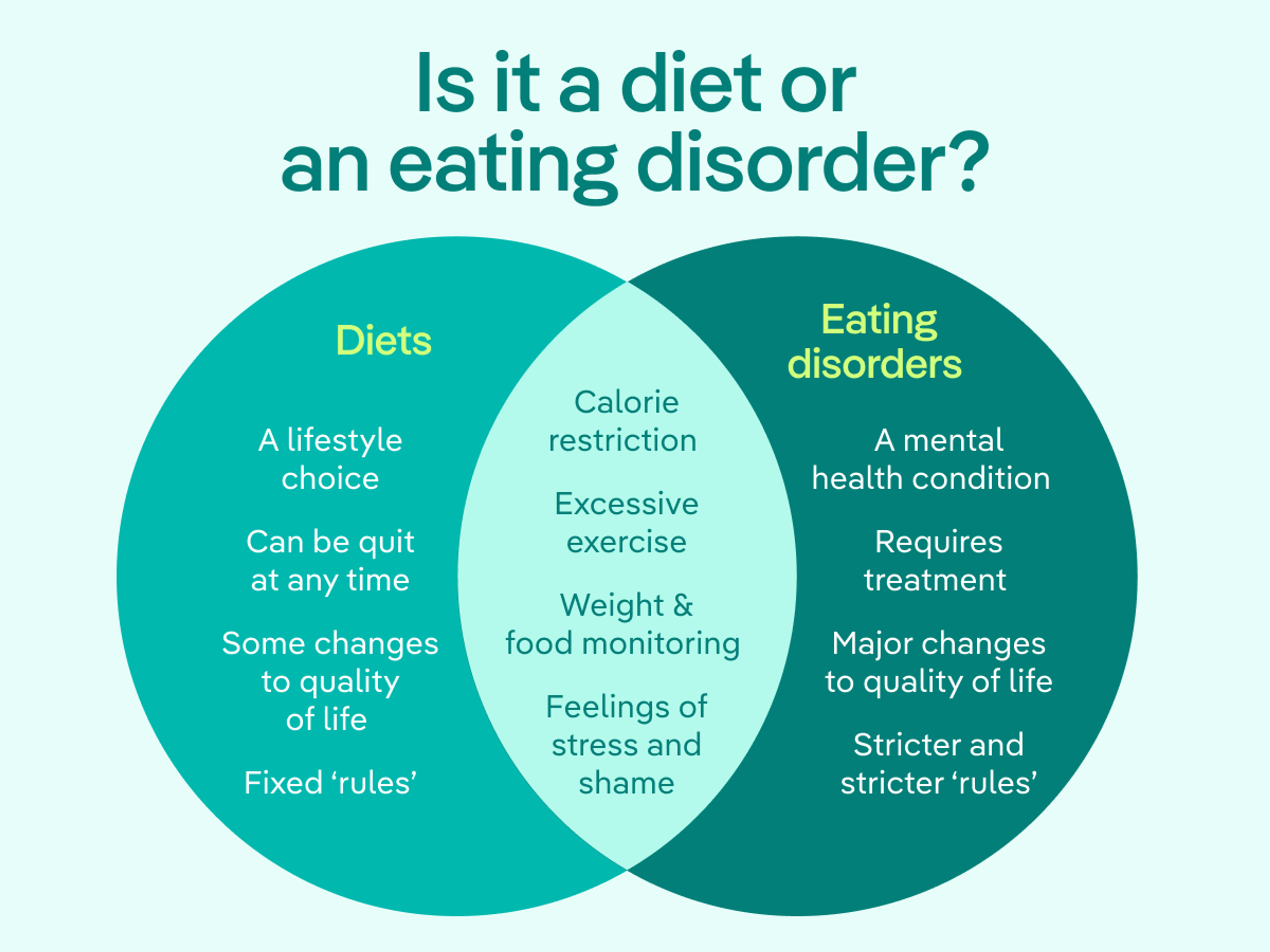

Both diets and eating disorders may include calorie restriction, excessive exercise, weight and food monitoring, and feelings of stress and shame. Generally speaking, diets:

- Are a lifestyle choice

- Can be quit at any time

- Cause some changes to quality of life

- Have fixed “rules”

Eating disorders, on the other hand:

- Are mental health conditions

- Require treatment

- Cause major changes to quality of life

- Have increasingly stricter “rules”

Can I go on a diet if I’m in recovery from an eating disorder?

In general, experts do not recommend weight loss diets for those in recovery from an eating disorder. Research has consistently identified dieting as one of the strongest predictors and a significant risk factor for the development of an eating disorder. Dieting can be a slippery slope for those predisposed to developing eating disorders, and diets themselves often promote the adoption of disordered eating behaviors. Rather than focusing on weight, experts suggest prioritizing health-promoting behaviors like stress management, adequate sleep, joyful movement, and more.

Is dieting the same thing as disordered eating?

No. Dieting and disordered eating are not the same thing, although they can overlap. Dieting is typically an intentional, structured attempt to change eating patterns (often for weight or health reasons). Disordered eating involves harmful, rigid, or distressing behaviors and thoughts about food, body image, or control—whether or not a person has received a formal diagnosis.

How can I tell if my loved one’s diet is actually an eating disorder?

While a diet is generally an eating plan that limits certain foods or portions with the goal of losing weight, eating disorders are serious mental health conditions marked by persistent, disruptive thoughts and behaviors around food. A diet is a personal lifestyle choice; an eating disorder is not. If you’re worried about someone you care about, our free eating disorder screener can help you figure out what to do next.

- Treasure, Janet et al. “Eating disorders.” Lancet (London, England) vol. 395,10227 (2020): 899-911. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30059-3

- Stice, E. “Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: A meta-analytic review.” Psychological Bulletin, 128(5) (2002), 825–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.825

- Levinson, Cheri A et al. “My Fitness Pal calorie tracker usage in the eating disorders.” Eating behaviors vol. 27 (2017): 14-16. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2017.08.003

- Romano, K.A., et al. Helpful or harmful? The comparative value of self-weighing and calorie counting versus intuitive eating on the eating disorder symptomology of college students. Eat Weight Disord 23, 841–848 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0562-6

- “Dieting in adolescence.” Paediatrics & child health vol. 9,7 (2004): 487-503. doi:10.1093/pch/9.7.487

- Boutelle, Kerri N et al. “Reduction in eating disorder symptoms among adults in different weight loss interventions.” Eating behaviors vol. 51 (2023): 101787. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2023.101787

- Memon, Areeba N et al. “Have Our Attempts to Curb Obesity Done More Harm Than Good?.” Cureus vol. 12,9 e10275. 6 Sep. 2020, doi:10.7759/cureus.10275