The information in this article originally appeared in an Equip Academy presentation, presented by Cara Bohon and Ally Duvall. Watch the presentation here, and register for future Equip Academy events to learn about other eating disorder-related topics and earn free CE credits.

Eating disorders often involve body image concerns. Addressing these concerns is an important part of treatment, as it helps protect patients against relapse and set them up for lasting recovery. One way to do this may be to challenge harmful appearance ideals, which are often a major contributing factor to body image distress—and research suggests that cognitive dissonance theory may be a particularly effective tool for dismantling deeply ingrained appearance ideals.

Here, we’ll evaluate the origins of appearance ideals and body image pressures; examine cognitive dissonance-based body image programs and the theory behind them; and explore how to incorporate specific cognitive dissonance-based approaches to decrease body image concerns.

Body image 101

So what exactly is body image? Let’s define the term.

Body image is something we all have. In the simplest terms, body image is a person’s experience in their body. This includes their:

- Perception of their body

- Thoughts about their body

- Emotional attitudes toward their body

- Behaviors toward their body

We often talk about “good” or “bad” body image, but it’s more nuanced than that. Body image concepts exist on a spectrum.

Negative body image

The concepts of “body judgment” and “body dissatisfaction” fall under the umbrella of negative body image.

This might show up as body checks, a drive for thinness, a distorted view of one’s self, body comparison, and a strong belief in appearance ideals.

Someone with a negative body image may say things like “If I looked like x, my life would be perfect,” or “I wish I was toned like you.”

Neutral body image

The concepts of “body neutrality” and “body trust” fall under the umbrella of neutral body image.

This might show up as focusing on body function or qualities versus appearance, neutral statements about one’s body, and self-compassion.

Someone with a neutral body image may say things like, “My body is the least interesting thing about me.”

Positive body image

The concepts of “radical self-love” and “body liberation” fall under the umbrella of positive body image.

This might show up as body activism, challenging appearance ideals, loving every single cell, body joy, and body positivity.

Someone with a positive body image may believe strongly in these words from author and activist Sonya Renee Taylor: “Making peace with your body is your mighty act of revolution. It is your contribution to a changed planet where we might all live unapologetically in the bodies we have.”

What are appearance ideals?

There are a number of different appearance ideals that can inform (and often harm) someone’s body image. It’s also important to recognize that not all of us experience the same appearance ideals, as some may be more dominant than others. Race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, disabilities, and gender identity can all influence what we are told is “ideal”.

Feminine ideal

When you think of the “perfect” girl or woman, how would you describe her?

Though answers may vary, people often respond with words like “slender,” “pretty,” “cute,” or “graceful.” We call this “look” the “feminine ideal.” It’s sometimes called the “thin ideal” because of the emphasis on overall thinness as one of the most important factors that represents femininity.

Masculine ideal

When you think of the “perfect” boy or man, how would you describe him?

Though answers may vary, people often respond with words like “strong,” “toned,” “muscular,” “lean,” or “handsome.” This is sometimes called the “muscular ideal” because of the emphasis on overall muscularity as one of the most important factors that represents masculinity.

Non-binary ideal

When you think of the “perfect” non-binary person, how would you describe them?

Though answers may vary, this is sometimes called the “androgynous ideal” because of the emphasis on overall androgyny as one of the most important factors that represents being non-binary.

You might rightly wonder, where do these appearance ideals come from? It’s complex.

We have to think about these appearance ideals in the context of various systems of oppression designed to limit who has access in our society. Some of the factors that inform and shape appearance ideals include:

- Fatphobia and anti-fat bias

- Racism and anti-blackness

- Transphobia

- Sexism

- Homophobia

- Ableism

Appearance ideals have deep, historical roots. The ideals have changed throughout history based on what will keep institutions, businesses, and privileged individuals profiting and in power. Even as they change, they continue to stay narrow, restrictive, and unobtainable for pretty much everyone. Currently, the appearance ideals are shifting back to the “thin aesthetic” from the early 2000s, with an emphasis on thin and flat stomachs.

Appearance ideals show up in our lives in many ways, including:

- Fashion, clothing, and beauty brands

- Harmful curriculum and peer interactions

- Comments from family, friends, colleagues, etc.

- How we view, talk about, and treat ourselves

- Media (TV, movies, social media, ads)

- Ill-informed diagnostic criteria, biased doctors

- Wellness or “lifestyle change” programs

- Biased research studies and measures

The harmful impact of appearance ideals

The pursuit of appearance ideals has a significant negative impact, both on an individual and a societal level.

Societally

According to Deloitte, appearance-based discrimination (defined as the unjust, prejudicial treatment of somebody purely based on their appearance) has a high cost. Their data shows that in a given year:

- Appearance-based discrimination (defined as the unjust, prejudicial treatment of somebody purely based on their appearance) leads to $269 billion in financial costs and $233 billion in lost well-being

- Weight discrimination affected 34 million people and cost $206 billion

- Skin shade discrimination affected 27 million people in the Black community and cost $63 billion

- Natural hair discrimination affected 5 million people in the Black community

- Body dissatisfaction (defined as having a severe and persistent negative attitude toward one’s own physical appearance, which has been caused by harmful beauty ideals) led to $84 billion in financial costs and $221 billion in lost well-being

Individually

Diet culture thrives on body image concerns, which are fueled by appearance ideals. In our diet culture-informed society, body image distress is extremely common among all populations.

- 41% of men think they are “too heavy” and are self-conscious about weight

- 60% of women think they are “too heavy” and are self-conscious about weight

- 80% of young teenage girls report fears of becoming fat

- 82% of adults believe weight loss is their responsibility

- 95% of people who diet regain weight they lost within 5 years

- $71 billion spent on dieting and weight loss in 2020

Not all people who struggle with body image will develop an eating disorder, but a significant subset will, and body image distress is often a contributing factor to (and symptom of) an eating disorder. In this year alone, 5.5 million people living in the United States will develop an eating disorder, and only 20% of them will receive treatment; an even smaller fraction will get evidence-based care that works.

Body image concerns, intense pressure to fit the appearance ideals, and the harsh reality of how many people will experience an eating disorder in their lifetime left researchers wondering: What if we could decrease negative body image concerns and prevent eating disorders from developing in the first place?

How appearance ideals can lead to an eating disorder

Eating disorders emerge out of a confluence of different genetic, biological, environmental, social, and other factors. Some common traits that predict the onset of an eating disorder are:

- Fear of weight gain

- Overvaluation of weight and shape

- Dieting

- Distorted self-perception

- Compensatory behaviors

- Thin-ideal internalization

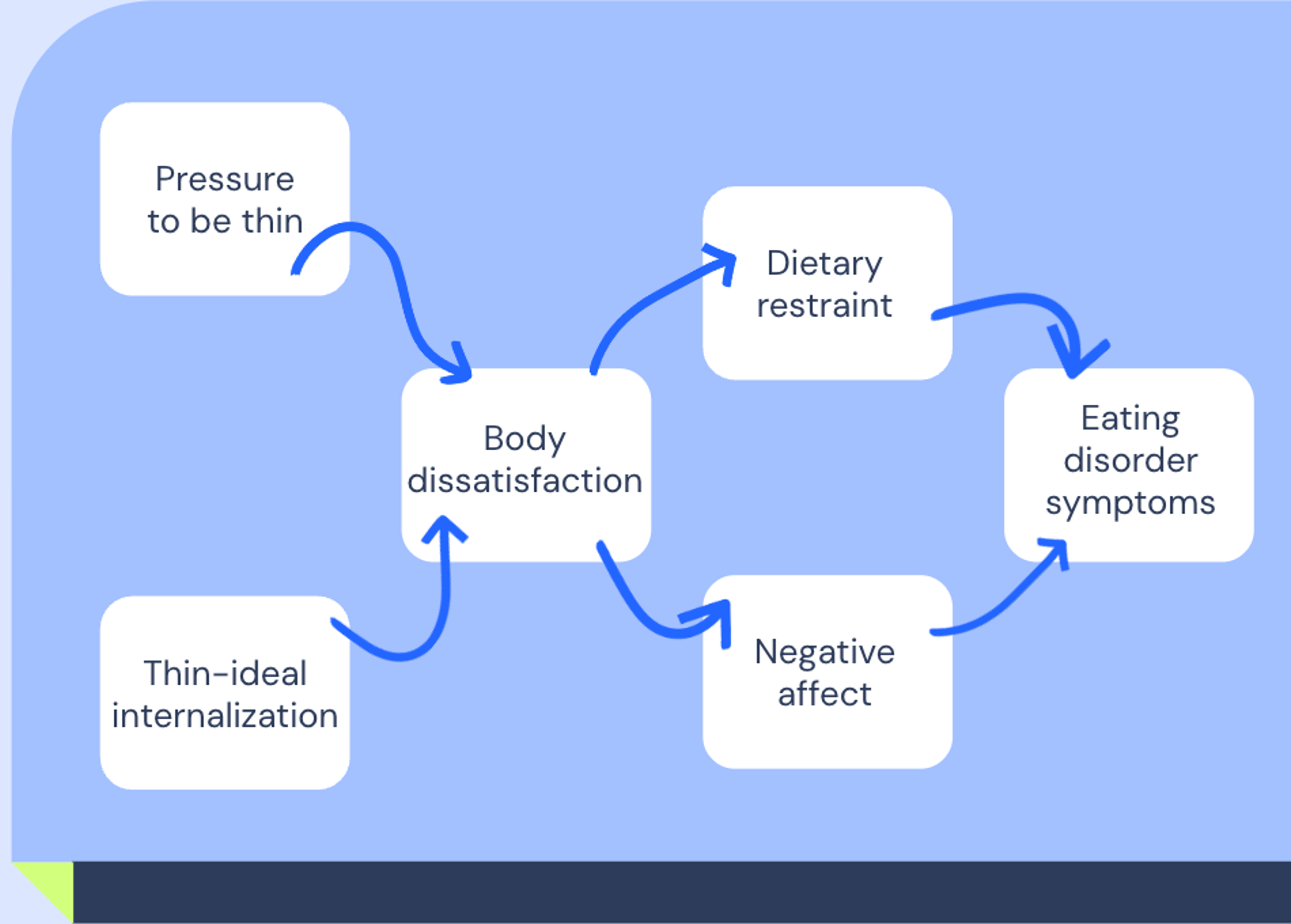

As researchers explored the emergence of eating disorder traits, a theory developed. Thin-ideal internalization (coupled with sociocultural pressure) starts the cascade effect contributing to body dissatisfaction, then dieting and negative affect, ultimately leading to eating disorder symptoms.

They wondered: If we could reduce thin-ideal internalization first, would the other risk factors decrease too?

Introducing cognitive dissonance theory

Research shows that education-based prevention programs are not very effective in creating attitudinal and behavioral change. The theory was put forth that cognitive dissonance could be effective in creating shifts in both beliefs and behaviors.

Learning information can feel good and helpful at first, but there is a difference between educating and empowering people to change. Research shows that disclaimers and warnings on photoshopped pictures or ads are unsuccessful at mitigating the body image distress created by unrealistic images in the first place. We often want to wait for our thoughts or emotions to change first before we alter our behaviors, but experiencing dissonance can actually empower us to act now.

Cognitive dissonance theory rests on the notion that as humans, we want to maintain consistency between our beliefs, values, and actions. When there’s a conflict between our beliefs and actions, we experience dissonance: mental distress like frustration, guilt, shame, discomfort, anxiety, etc. Dissonance is uncomfortable, so we seek out ways to reduce the conflict and return to a state of consistency. We might do this in one of a few different ways:

- Reject: add in more affirming beliefs to override the conflicting belief/behavior

- Rationalize: attempt to decrease the importance of the conflicting belief/behavior

- Rethink and revise: change and adapt toward the new belief or behaviors

Consider this example: Drew, an eco activist, bought their dream car: a Chevy truck with a diesel engine—and their sister just showed them a graph of how high diesel emissions are and says Drew’s car is awful. To reduce cognitive dissonance, Drew could:

- Reject: by going to chevysRthebest.com and reading how Chevy trucks aren’t bad for the environment because they R the best.

- Rationalize: by saying their car might not be the best for the environment, but Drew recycles and takes short showers so it all works out fine for their carbon footprint (and their car still totally rocks).

- Rethink and revise: by turning their car into a dealership and leaving with an eco-friendly truck, realizing their diesel Chevy wasn’t the best car for them because they care about their environmental impact.

It’s important to note that the amount of dissonance that you experience can be influenced by how highly you value a belief or the degree to which your beliefs are inconsistent. For instance, Drew might experience decreased dissonance if his best friend Betty, who died last year, also loved driving a diesel Chevy truck and they bonded over that belief, making this a deeply held value for Drew. On the other hand, his dissonance might increase if this was the eighth time Drew heard new information on why diesel Chevys aren’t the best cars, so they had a larger drive to change cars.

The Body Project: using cognitive dissonance to challenge appearance ideals

Dr. Eric Stice and team developed the dissonance-based eating disorder prevention program The Body Project. The Body Project includes verbal, written, and behavioral exercises designed to position girls to argue against the appearance ideals, as well as discussion-based groups with Socratic questions to highlight costs of pursuing the thin ideal for girls. It was the first prevention program to reduce eating disorder symptoms, and Initial trials showed reduced risk factors and eating disorder symptoms over a short period follow-up.

After many years of research and multiple iterations, large efficacy trials revealed The Body Project as the most effective compared to seven other credible interventions in reducing eating disorder symptoms, including thin internalization. Many research teams have replicated these results across languages, countries, and program audience adaptations: The PRIDE Body Project, More Than Muscles, The EVERYbody Project, etc.

The “high dissonance” version of the project showed greater reductions in risk factors and eating disorder symptoms, leading to new program updates, like increased voluntariness of participation, public accountability, and difficulty of exercises. The three- to four-hour intervention produced significant reductions in symptoms that remained three and four years after the intervention was completed. Additionally, fMRI imaging revealed The Body Project participants had decreased activation in reward response (Caudate) when shown thin models compared to the control group.

Applying cognitive dissonance theory in practice

There are a number of different strategies you can employ to apply the learnings of this research with your own patients.

Some ways to increase dissonance in sessions include:

- Have patients volunteer and consent to participate, share their thoughts, and complete activities (increases their agency).

- Increase the amount of accountability by having patients sign their home activities or encouraging sharing.

- Introduce roleplay activities designed to put patients in the position of directly challenging their previous beliefs.

- Resurface the dissonance continually, as appropriate. Repetition will increase the degree to which their beliefs and actions conflict.

- Utilize activities designed to solidify the new beliefs patients are building from your sessions (letters, lists).

- Engage in Socratic discussions that challenge or explore the impacts of the ideals—let the patient be the main contributor!

Here are some concrete examples of what that might look like.

Costs of pursuing the ideals

Ask your patient to list out the costs of pursuing the ideals. This can be a collaborative activity where you work together to build a comprehensive list—just ensure the patient is the one leading and contributing. The list might include items like:

- Loss of self and personality

- Loss of connections

- Mental health

- Physical health

- Hobbies, passions

- Time with my dog

- Memories and pictures

- SO much time and money

- Food and body freedom

Roleplays

This activity is designed to have the participant argue against the ideals by talking you (the provider) out of pursuing them. Choose a character who is struggling to see the impact of pursuing the ideals and ask the patient to tell you why you should stop these behaviors.

Go back and forth, making more space for them to share the costs of pursuing these ideals

Reflect after: how did it feel to challenge these thoughts?

Letter to younger self

Ask your patient to think of what advice they would share or things they would say to their younger self about how to build a supportive relationship with their body. You can encourage the patient to think of what they have learned in your sessions or throughout their experiences.

Important note: this letter does not need to pretend that everything they have experienced could be avoided if they did x, y, x. The focus is to have them write out ways to challenge the ideals, not to change the past.

Negative body talk

This activity is designed to have the participant challenge negative body talk statements they encounter in their life. Using a list of negative body talk statements, say the phrase to the patient and have them respond in a quick way that challenges the comment. Practice multiple, and ask the patient if they have any comments they would like to practice challenging.

Negative body talk examples might include:

- Do I look fat in this?

- What are you, a girl or a boy?

- You should lose some weight…only for your health!

- Where are her curves?? I thought she was Mexican.

- I’m so out of shape.

- Why do they have a beard? I thought they were non-binary.

Reflect after: how did it feel to challenge these thoughts in the moment? How can you use these going forward?

Explore opposite action

Ask your patient, what would you be doing if you weren’t concerned about your body? What clothes would you wear? What activities would you do? How would you talk to yourself? How would you interact with others? Then help them identify steps they can take to start doing those things right now:

- Practice wearing the crop top

- Practice saying kind things to your body out loud

- Plan time to play your favorite game with friends

“Doing the thing” multiple times can help retrain your brain to enjoy the things you are currently avoiding due to body image concerns.

For more in-depth information on using cognitive dissonance theory to help your eating disorder patients challenge appearance ideals, watch my recorded Equip Academy presentation on the topic.

Our free, self-guided body image program, Explore: Freeform employs cognitive dissonance theory to help participants push back against thin ideals and feel more empowered in their body. Learn more about Explore: Freeform here.

- Fildes, Alison et al. “Probability of an Obese Person Attaining Normal Body Weight: Cohort Study Using Electronic Health Records.” American journal of public health vol. 105,9 (2015): e54-9. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302773

- Frederick, David A et al. “The swimsuit issue: Correlates of body image in a sample of 52,677 heterosexual adults.” Body image vol. 3,4 (2006): 413-9. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.08.002

- Kearney-Cook, Ann et al. “Body Image Disturbance and the Development of Eating Disorders.” In The Wiley Handbook of Eating Disorders (eds L. Smolak and M.P. Levine). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118574089.ch22

- Pearl, Rebecca L et al. “Prevalence and correlates of weight bias internalization in weight management: A multinational study.” SSM - population health vol. 13 100755. 17 Feb. 2021, doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100755