The information in this article originally appeared in an Equip Academy presentation. Watch the presentation here, and register for future Equip Academy events to learn about other eating disorder-related topics and earn free CE credits.

ARFID is often dismissed or left undiagnosed because it’s viewed as “just” picky eating — and it’s true that in a lot of cases, picky eating is normal and completely harmless. The tricky part for parents and healthcare professionals is finding the line between developmentally appropriate pickiness and a concerning problem.

So how picky is too picky? Knowing that many children may tend towards pickiness during childhood, at least for a time, how, as a pediatrician or provider do you know when it is time to intervene? It’s an important question to answer: a study published in Pediatrics in 2015 provided evidence that even moderate levels of picky eating in toddlerhood were associated with adverse physical and mental health outcomes.

Defining Selective Eating

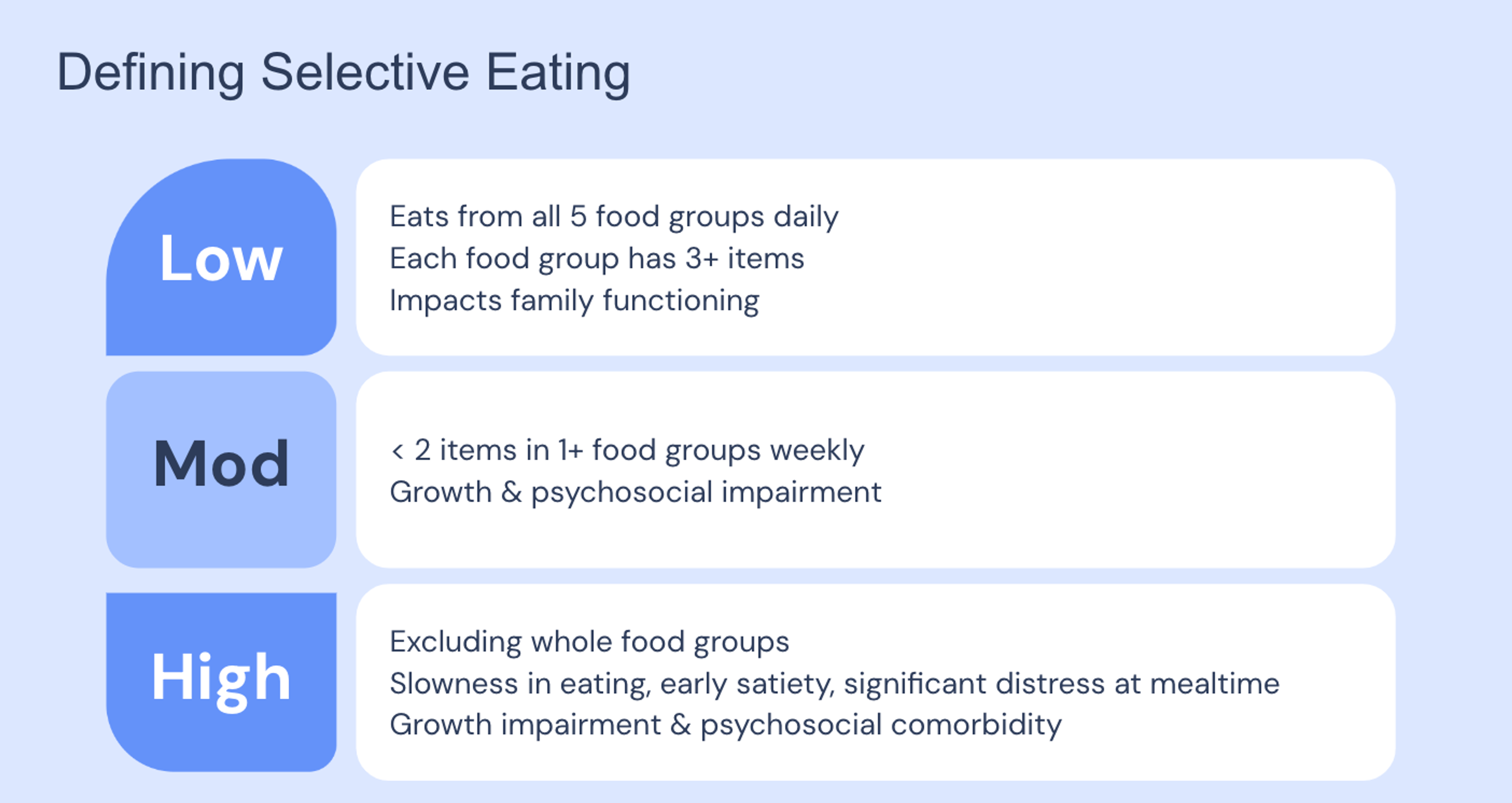

One of the most well-operationalized definitions of picky eating severity that I’ve found was published by Dr. Will Sharp, PhD, who runs the feeding disorders program at the Marcus Autism Center in Atlanta. While his definitions of picky eating severity weren’t used in the studies I’ll be discussing here, his methods of defining picky eating have high clinical utility. He breaks down picky eating severity based on both selectivity and mealtime behavior and their associated risk for nutritional deficiency and food rejection.

Put very simply, a child with low levels of pickiness is one who eats from all five food groups (starches, fruits, vegetables, proteins, and dairy) on a daily basis and who eats at least three items from each of these food groups. Children with low levels of pickiness might still have some negative impact on family functioning, in that they still may be a bit difficult to please, but risk to physical development is minimal.

Children with moderate levels of pickiness have at least one food group in which they accept a low number of items on a weekly basis. In other words, they eat from all five food groups, but at least one of those food groups is consumed infrequently and has little variety. So think here of a child who might eat two vegetables, but definitely not daily and maybe only once or twice a week.

Children with high levels of pickiness completely reject one or more food groups (for instance, refusing to eat any fruits and any dairy), and accept five or fewer total food items. They also may eat slowly, feel full early, and/or experience significant distress at mealtime.

Moderate and high levels of pickiness are both associated with more significant mental and physical health risks than low-level pickiness, including risks of micro- and/or macro-nutrient deficiency (scurvy, iron deficiency anemia, kwashiorkor).

How does ARFID fit into all this?

First, let’s define ARFID. ARFID stands for avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, and it’s an eating disorder characterized by problems with either volume or variety of food intake (not eating enough food or enough types of food) that are not driven by a desire to lose weight, a fear of gaining weight, or a desire to change one’s body. The selective eating behaviors associated with ARFID cannot be explained by an existing medical or mental health condition.

ARFID can stem from several different causes. The primary presentations are:

- Fear of adverse consequences from eating (like choking or getting sick)

- Selective eating due to sensory sensitivity (i.e., disliking certain textures, smells, or tastes)

- Lack of interest in food and eating

ARFID is a serious eating disorder that can cause a variety of impairments to patients’ mental and physical health as well as their daily life. ARFID can lead to:

- Weight loss or failure to grow

- Nutritional deficiency

- Dependence on enteral feeding or oral supplements

- Problems in daily living

Another condition to be aware of is DSM-IV-TR Feeding Disorder Diagnosis, which is similar to ARFID in many ways but differs in that the diagnostic criteria doesn’t include a weight loss or growth impairment requirement, and it can exist within the context of another medical condition.

When to intervene in picky eating

Eating preferences are unique, and selective eating can be normal. So when do we worry? When, as healthcare providers, should we do something?

Thankfully, there are some clear signs that can indicate it’s time to take action. Red flags in a patient include:

- Not eating at least one food from all five food groups on a weekly basis

- Losing weight or falling off the growth curve

- Struggling to eat enough food, period

- Refusing to try new foods

- Tantrums or intense emotional distress when presented with non-preferred food

- Not responding to intervention

There are a number of different measures you can use to determine if a patient’s eating has become too selective. One option is to look at nutritional adequacy through blood tests and/or food frequency assessments. Food frequency is a measure of how frequently a person consumes different types of food, and there are a few different options for measuring this, including The Primary Food Groups Building Blocks (in CBT-AR manual), food recall (food eaten over a 48-hours or four-day period), and always-sometimes-never lists (foods they’ll always eat, foods they’ll sometimes eat, and foods they’ll never eat).

You can also look at the characteristics of their selective eating to determine if it’s a problem.

Picky eating

- Strong preferences for specific types of foods, brands, or preparations

- May try new things, eats from all five foods groups on a regular basis (even if it’s not a lot of foods)

- Growing okay, eating doesn’t cause too many problems

ARFID

- Strong and narrow preferences for types of foods, brands, or preparation

- Excludes whole food groups or eats certain types of food on an infrequent basis, refuses to try new foods

- Growth impairment, health & social consequences, distress

Treatment of selective eating

When treating selective eating, it’s important to remember that it arises out of a variety of different contributing factors, including:

- Early exposure to foods

- Genetics

- Personality factors

- Cultural norms

- Innate dispositions

- Familiarity/modeling

- Physiological factors

Neurodiversity can also play a role—up to 89% of children with autism have feeding differences. Neurodiversity especially shapes eating preferences when it comes to:

- Sensory sensitivity: Hypo- or hyper-sensory processing differences with respect to taste, texture, smell, temperature, look, and sounds related to eating (or the eating environment)

- Cognitive rigidity: Strong preferences for sameness, consistency, and predictability. Impacts food choice, willingness to try new foods, other preferences (like meal preparation, location, etc.)

- Gastrointestinal issues in autism: Painful or negative experiences with food or eating related to underlying gastrointestinal disorders

Selective eating and ARFID are best treated by neither overly accommodating patients’ preferences (preparing alternate meals, not persisting with new foods, not offering foods again, allowing escape) nor pressuring them to eat (focusing on liking versus trying, using of judgmental language, overwhelming them with new foods). It’s best to keep an agnostic frame of reference in mind when approaching patients and caregivers about these factors.

The treatment of selective eating can be broken down into three broad steps.Before completing this plan, it’s important to address any other factors that might be impacting eating before addressing variety:

Step 1: Establish weight gain or regular eating. Make sure the patient is getting enough to eat first.

Step 2: Make a plan for dietary expansion.

Step 3: Start dietary expansion.

There are a number of different evidence-based modalities for treating ARFID and feeding difficulties. These include:

Feeding therapy

Could include any of the following:

- Behavioral intervention (ABA; large evidence base)

- Sequential Oral Sensory (SOS) approach to feeding

- Responsive feeding or Division of Responsibility

Family-Based Treatment for ARFID (FBT - AR)

Family approach

- Evaluated in children ages 5-12

- No specific approach to expanding dietary variety

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for ARFID (CBT - AR)

Individual or family-based

- Suitable for ages 10+, only manual treatment for adults

- Incorporates SOS + mindfulness for dietary expansion

Conclusion: What to remember about selective eating and ARFID

Here’s what providers should know about differentiating ARFID, selective eating, and picky eating from one another, as well as how to treat ARFID or selective eating.

Picky eating is transient; selective eating is persistent. It will not get better with time. Both involve eating a narrow range of foods, difficulty trying new foods, and are difficult to please.

ARFID differs from selective or picky eating in that the eating has resulted in:

- Weight loss or poor growth

- Nutritional deficiencies

- Dependence on supplements

- Impairment in social/emotional functioning

Taste is complicated. Sensory perception is involved, but cognitive rigidity and disgust also influence persistence of selectivity. Providers should set fair expectations for treatment, work with caregivers to modify behavior as needed, and expand diet through exposure.

For more in-depth information on diagnosing and treating selective eating, including strategies for setting expectations, modifying caregiver behaviors, introducing new foods, systematic desensitization, and more, watch my recorded Equip Academy presentation on the topic.

To refer a patient or learn more about Equip’s evidence-based eating disorder treatment for ARFID, schedule a call with our team.

- Zucker, Nancy et al. “Psychological and Psychosocial Impairment in Preschoolers With Selective Eating.” Pediatrics vol. 136,3 (2015): e582-90. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-2386

- Sharp, William G et al. “Feeding problems and nutrient intake in children with autism spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis and comprehensive review of the literature.” Journal of autism and developmental disorders vol. 43,9 (2013): 2159-73. doi:10.1007/s10803-013-1771-5

- Lukens, Colleen Taylor, and Alan H Silverman. “Systematic review of psychological interventions for pediatric feeding problems.” Journal of pediatric psychology vol. 39,8 (2014): 903-17. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsu040

- Kohane, Isaac S et al. “The co-morbidity burden of children and young adults with autism spectrum disorders.” PloS one vol. 7,4 (2012): e33224. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033224