- There is significant overlap between eating disorders, suicidality, and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI)

- There are a number of signs of suicidality and NSSI that providers should know how to recognize. This includes behavioral signs and physical signs. There are also several clinically validated assessments providers can use.

- Treatment for overlapping eating disorders and self-harm includes a) a safety plan; s) lethal means counseling; and c) evidence-based treatment.

The information in this article originally appeared in an Equip Academy presentation. Watch the presentation here, and register for future Equip Academy events to learn about other eating disorder-related topics and earn free CE credits.

The unfortunate reality is that people affected by eating disorders are at an elevated risk for experiencing suicidality and engaging in nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI). Knowing how to identify and address both issues effectively can be a challenge for healthcare providers, but it is crucial to saving lives. Today, I’ll provide an overview of the connection between eating disorders and suicidality, how to identify suicidality or NSSI in eating disorder patients, and what providers can do to reduce risk of suicidal and self-harming behaviors.

I’m going to be talking about scientific theory and clinical applications, but I want to ground what we’re talking about in the individuals we work with. Why is this topic important?

It matters because of people like my former patient "Mary” (not her real name). She was 16 years old, struggling with bulimia, and wanted to recover but felt unheard and unsure how to express herself. In desperation, she began cutting herself to try to cope with the pain she experienced. Through therapy, she was able to find new ways to cope and a path forward—and it’s for patients like “Mary” that this work is so important.

Overlap of suicidality, NSSI, and eating disorders

First, let’s define the terms we’re using:

Suicidality: self-harming behaviors meant to end one’s life. Suicidality is often indicated by signs like suicidal ideation, having a suicide plan, or past suicide attempts.

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI): deliberate self-harm without any intention of death as a result. NSSI doesn’t include culturally sanctioned self-harm, such as piercings or tattoos. Though NSSI involves no intent to die, it is associated with elevated risk of suicide.

Eating disorders: mental health conditions characterized by persistent disturbed eating behaviors that negatively impact physical and psychological health

Current research suggests that self-injury most commonly begins between ages 12 and 15, with a second onset peak in early adulthood, around age 20. Typically, rates of self-injury increase through early- to mid-adolescence, and decline in later adolescence. Note that these are just tendencies, and suicidality or NSSI can occur at all stages of life: some people first start to self-injure before the age of 12 (in which case it is is associated with more severe self-injury over a longer period of time), and some first self-injure much later in life.

A 2015 meta-analysis of 116 studies showed that girls and women are slightly more likely to self-injure than boys and men, with this gender difference particularly evident in clinical samples. Self-injury is also more common among individuals identifying within the LGBTQIA+ community, with rates two to three times that of heterosexual/cisgender individuals.

There is significant overlap between eating disorders, suicidality, and NSSI. The estimated lifetime prevalence of NSSI in the general population is 4.86%, compared to significantly higher rates among those with eating disorders. According to a 2020 review:

- 33% of people with bulimia nervosa report NSSI

- 22% of people with anorexia nervosa report NSSI

- 20% of people with binge eating disorder report NSSI

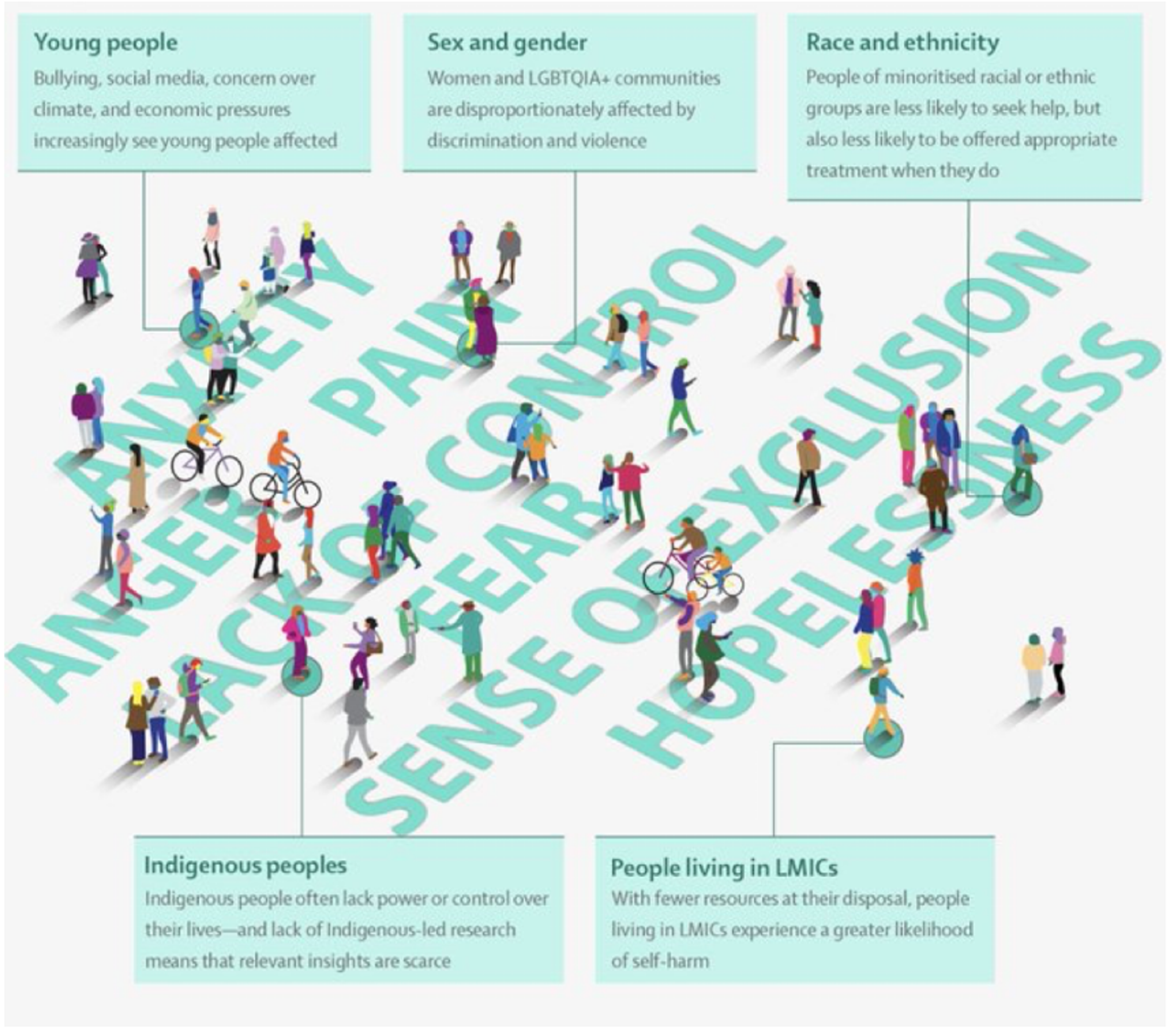

NSSI must be understood as an individual experience that occurs in an interpersonal, community, and societal context. Different factors can contribute to NSSI in different populations and demographics, as illustrated by the graphic below.

In terms of suicidality, rates are also higher among those with eating disorders. While about 4% of the general population have had suicidal thoughts, up to a third of people with eating disorders have thought about suicide, and one quarter to one third of people with eating disorders have made a suicide attempt. Among people with anorexia nervosa, suicide is the second leading cause of death.

Why do NSSI, suicidality, and eating disorders overlap?

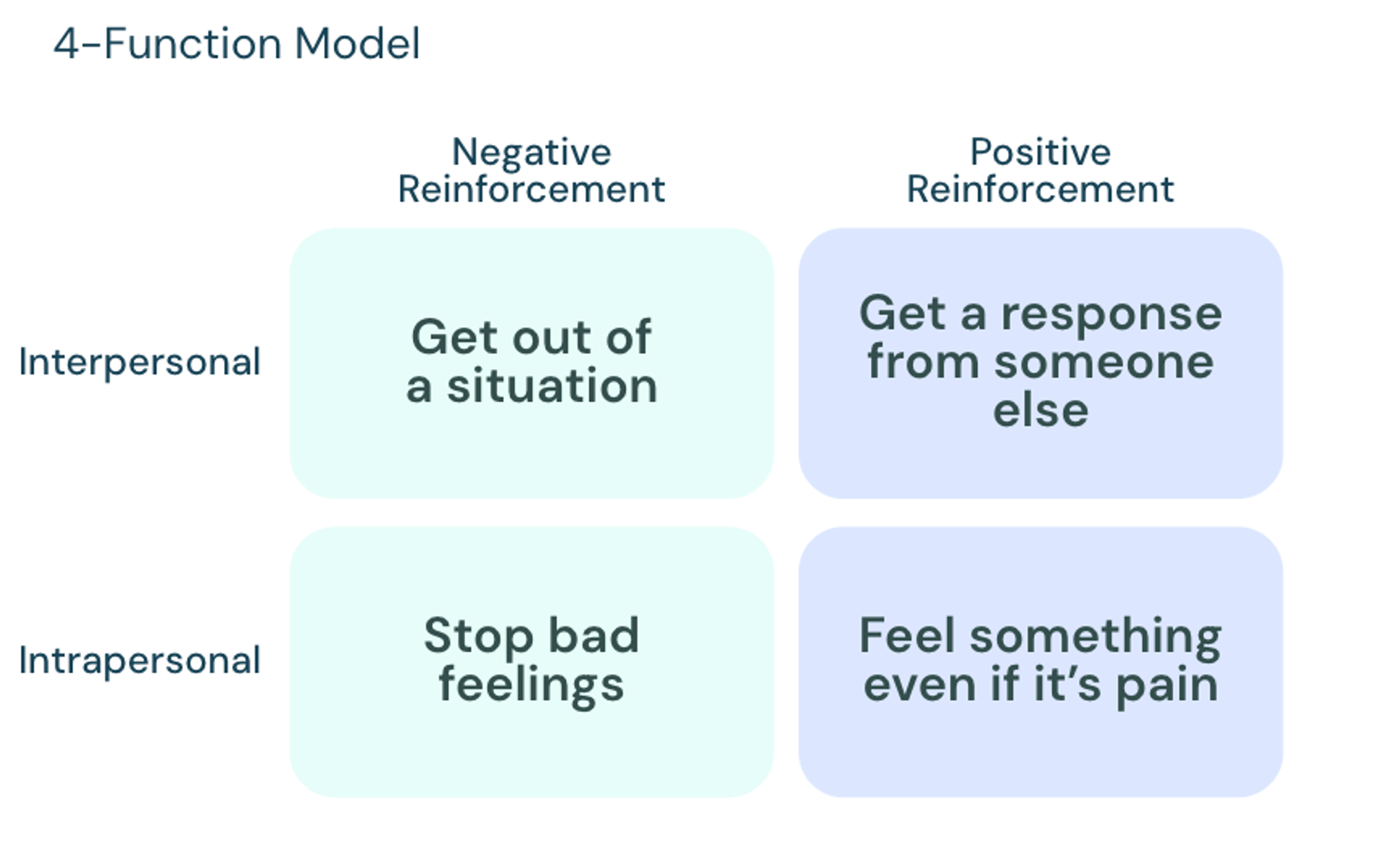

There are several different ways to understand the overlap between NSSI and eating disorders. One way to think about it is through the four-function model of NSSI, a framework which hypothesizes that NSSI is maintained by four different reinforcing processes: interpersonal negative reinforcement, interpersonal positive reinforcement, intrapersonal negative reinforcement, and intrapersonal positive reinforcement.

According to a 2023 study, NSSI in eating disorder patients is reinforced by the negative functions: interpersonal negative reinforcement, and intrapersonal negative reinforcement. In both cases, the NSSI is a means of escaping, either from distressing feelings or a particular situation.

You can think about the relationship between suicidality and eating disorders by looking at the three-step theory of suicide, which theorizes that suicide results from a combination of pain and hopelessness. The theory assesses the risk of suicide or suicidal ideation by asking a series of three questions:

1. Are you in pain or hopeless?

An answer of “No” indicates no suicidal ideation, while an answer of “Yes” indicates suicidal ideation.

If the answer to question 1 is yes, move to question 2.

2. Is your pain greater than your connections to life?

An answer of “No” indicates modest suicidal ideation, while an answer of “Yes” indicates strong suicidal ideation.

If the answer to question 2 is yes, move to question 3.

3. Are you capable of attempting suicide?

An answer of “No” indicates ideation only, while an answer of “Yes” indicates the risk of a suicide attempt.

While not everyone with an eating disorder will have suicidal ideation or suicidality, when you consider these questions in the context of the experience of having an eating disorder, it’s apparent why those with eating disorders are at heightened risk. People with eating disorders often feel emotional and psychological pain, which their disordered behaviors (paradoxically) both perpetuate and help them cope with. It’s also common for those with eating disorders to feel hopeless that things can get better, a problem exacerbated by barriers to diagnosis and treatment. These factors together contribute to an increased risk of suicidal ideation and suicide.

Assessment of NSSI and suicidality

The first step toward helping people struggling with both an eating disorder and suicidality or NSSI is knowing what to look for. In addition to knowing how to screen for eating disorders, healthcare providers should be knowledgeable about the signs and symptoms of NSSI and suicidality in patients.

Signs of NSSI

Common forms of nonsuicidal self-injury include cutting, burning, scratching, biting, and headbanging.

Physical signs

- Scarring, fresh cuts, burns or scratches

- Wearing long sleeves and pants even in hot temperatures; several bracelets on arms

- Having or collecting sharp objects

Behavioral signs

- No longer engaging in things they once enjoyed; isolating themselves

- Reporting feelings of hopelessness and worthlessness

- Secretive behavior

Signs of suicidality

Suicidality can show up in many different ways, including mood changes (like becoming increasingly agitated), or sleep disturbances like insomnia or nightmares. Another way to assess the risk of suicidality is through the acronym “IS PATH WARM?”

I: Ideation

Talking of wanting to die, looking for ways to die, talking about death

S: Substance abuse

Increased or excessive substance use (alcohol or drugs)

P: Purposelessness

No reason for living; no sense of purpose in life

A: Anxiety

Anxiety, agitation; inability to sleep

T: Trapped

Feeling trapped, like there's no way out; resistance to help

H: Hopelessness

Hopelessness about the future

W: Withdrawal

Withdrawing from friends, family and society; sleeping all the time

A: Anger

Rage, uncontrolled anger; seeking revenge

R: Recklessness

Acting recklessly or engaging in risky activities, seemingly without thinking

M: Mood changes

Dramatic mood changes

Assessment tools for clinicians

In addition to keeping the signs and symptoms above in mind, healthcare providers can also use a variety of different clinically validated screening tools to assess the risk of NSSI or suicidality.

NSSI assessment tools

- The Brief NSSI Assessment Tool: This 12-item assessment focuses on forms, functions, recency, frequency, habituation, and perceived life interference. It is freely available on the Cornell website.

- NSSI Decisional Balance, Processes of Change, & Self-Efficacy Scales: More focused on change, including motivation, confidence, and tools.

Suicidality assessment tools

- Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Individuals engaging in even one item from this scale are eight to 10 times more likely to die from suicide. Available at the Columbia Lighthouse Project.

- Ask Suicide-Screening Questions: There are different versions of this assessment, and it is available for free at Zero Suicide.

When assessing for the risk of NSSI or suicide, it’s important to create a safe environment for the patient that encourages them to open up about what they are struggling with. Providers should aim to be:

- Direct and transparent

- Collaborative

- Nonjudgmental

- Compassionate

- Authentic

- Open-ended

It is also important to involve supports as appropriate and be flexible in communication.

Risk reduction for NSSI and suicidality

Providers can save lives by taking steps to reduce the risk of NSSI and suicidality among patients. There are three primary means of risk reduction: developing a safety plan, lethal means counseling, and evidence-based treatment.

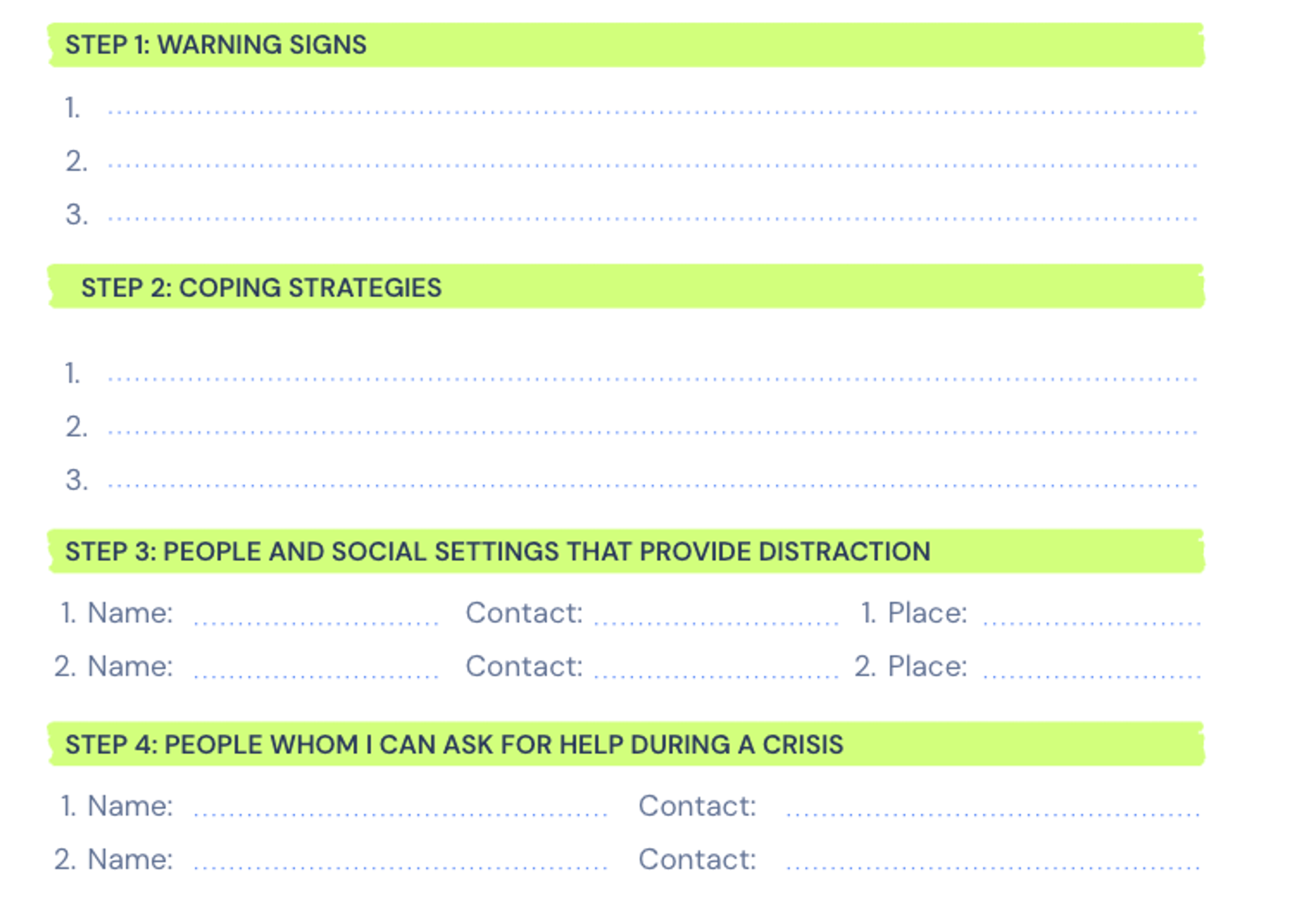

Safety plan

A safety plan gives patients something to turn to if and when they feel the urge to hurt themselves. It’s important that the safety plan is made collaboratively with the patient, and that they have easy access to it at all times. There are several different versions of safety plans, but the Stanley-Brown version (below) is a good example. Safety plans can also include reasons for living and steps the patient can take to make themselves safe.

Lethal means counseling

Lethal means counseling refers to assessing whether a person at risk for suicide has access to guns or other lethal means, and then working with them and their loved ones to limit their access to these items.

Lethal means counseling may include:

- Restricting access to lethal means (e.g., firearms, sharps, medications)

- Firearm safety (VA resource)

- Counseling on Access to Lethal Means course (Zero Suicide)

Evidence-based treatments

Patients struggling with eating disorders and NSSI or suicidality need access to evidence-based treatments that can address both conditions.

Evidence-based approaches to address NSSI and suicidality include:

- Brief cognitive behavioral therapy for suicide prevention (BCBT-SP)

- Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT)

- Collaborative assessment and management of suicidality

Evidence-based approaches to address eating disorders include:

- Family-based treatment (FBT)

- Enhanced cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT-E)

- Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT)

Additional considerations

When treating patients dealing with NSSI or suicidality, you can help support their recovery by working on the following focus areas:

- Increasing emotional safety

- Building emotional and communication skills

- Developing strategies to soothe pain

- Working on problem solving skills

- Fostering hope

- Strengthening connections with others

- Making meaning

As a provider, it’s important to use the patient’s chosen pronouns and validate their feelings and experiences. It can also be helpful to keep the three-step theory of suicide and four function model of NSSI in mind as you work with patients, to help you better understand what may be driving their feelings and how you can redirect them.

When dealing with such urgent and life-threatening issues, it’s vital to keep hope alive. A quote that resonates with me, and may with you, is this one from Albert Schweizer: “Always hold firmly to the thought that each of us can do something to bring some portion of misery to an end.”

For more information on addressing suicidality in eating disorder treatment, watch my recorded Equip Academy presentation on the topic. You can also explore past Equip Academy presentations and register for upcoming events here.

- Plener, Paul L et al. “The longitudinal course of non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm: a systematic review of the literature.” Borderline personality disorder and emotion dysregulation vol. 2 2. 30 Jan. 2015, doi:10.1186/s40479-014-0024-3

- Gandhi, Amarendra et al. “Age of onset of non-suicidal self-injury in Dutch-speaking adolescents and emerging adults: An event history analysis of pooled data.” Comprehensive psychiatry vol. 80 (2018): 170-178. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.10.007

- Muehlenkamp, Jennifer J et al. “Self-injury Age of Onset: A Risk Factor for NSSI Severity and Suicidal Behavior.” Archives of suicide research : official journal of the International Academy for Suicide Research vol. 23,4 (2019): 551-563. doi:10.1080/13811118.2018.1486252

- Bresin, Konrad, and Michelle Schoenleber. “Gender differences in the prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury: A meta-analysis.” Clinical psychology review vol. 38 (2015): 55-64. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.009

- Liu, Richard T et al. “Prevalence and correlates of non-suicidal self-injury among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Clinical psychology review vol. 74 (2019): 101783. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101783

- Liu, Richard T. “The epidemiology of non-suicidal self-injury: lifetime prevalence, sociodemographic and clinical correlates, and treatment use in a nationally representative sample of adults in England.” Psychological medicine vol. 53,1 (2023): 274-282. doi:10.1017/S003329172100146X

- Kiekens, Glenn, and Laurence Claes. “Non-Suicidal Self-Injury and Eating Disordered Behaviors: An Update on What We Do and Do Not Know.” Current psychiatry reports vol. 22,12 68. 10 Oct. 2020, doi:10.1007/s11920-020-01191-y

- Schmidt, Kendall et al. “Influence of nonsuicidal self-injury functions on suicide risk in individuals with eating disorders.” Suicide & life-threatening behavior vol. 53,6 (2023): 1055-1062. doi:10.1111/sltb.13006