- Eating disorder relapse is a common part of the recovery journey, affecting 31-41% of patients.

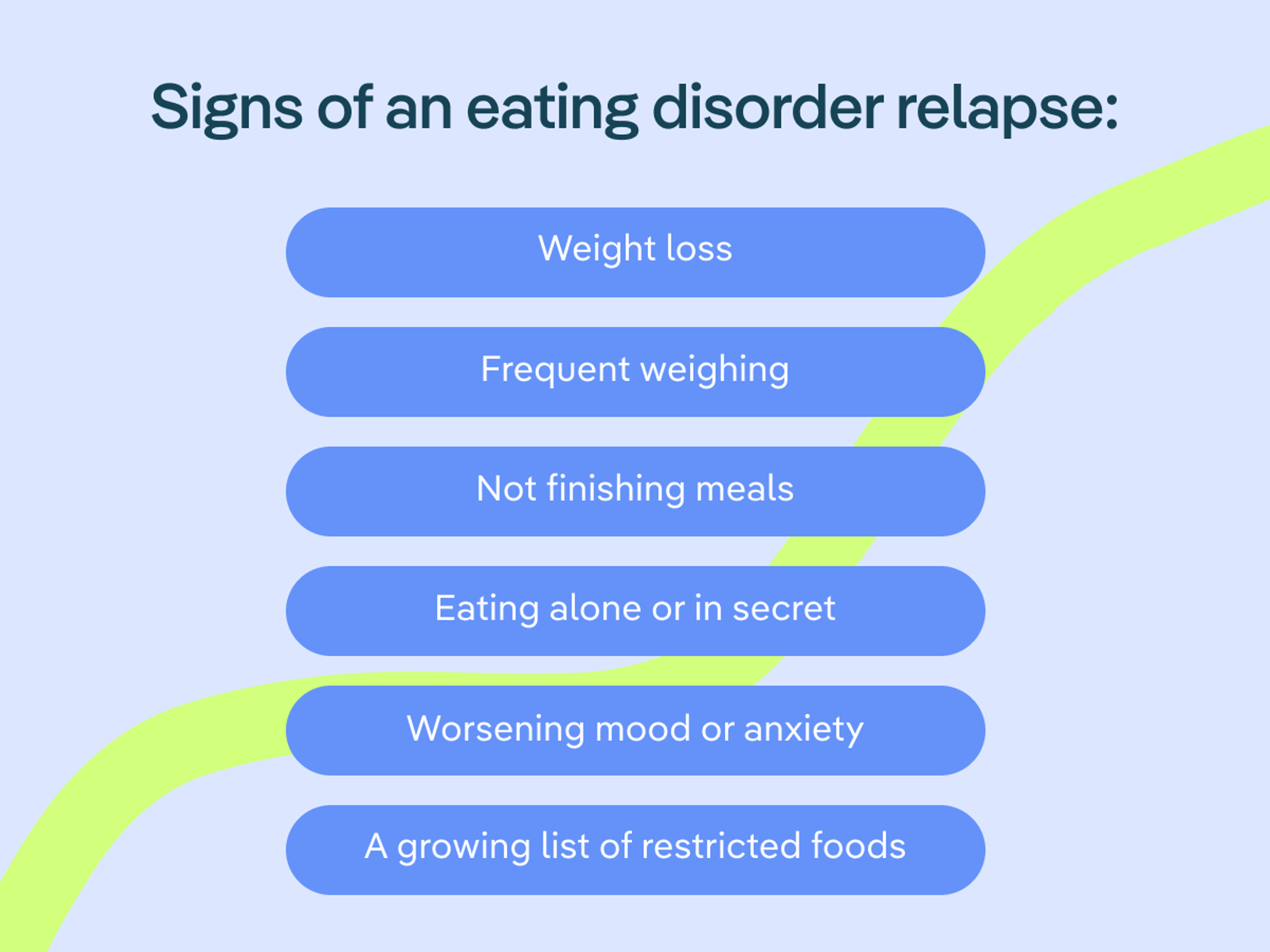

- Relapse looks different from person to person, but some of the most common signs include weight loss, not finishing meals, mood changes, and preferring to eat alone.

- If you or someone you love may be experiencing an eating disorder relapse, it's important to intervene quickly. Returning to regular eating habits and the skills learned in treatment is an essential first step. If you need additional support, reach back out to your care team.

As anyone who has ever navigated an eating disorder knows, recovery can be messy, uncomfortable, and far from direct. Relapses—typically defined as a return of symptoms after a period of relief—are common among eating disorder patients, with an estimated 31-41% of patients relapsing within two years of receiving treatment.

“Relapses can and often do occur—in fact, almost half of all people with an eating disorder will experience a relapse,” says Equip’s VP of Program Development, Jessie Menzel, PhD. There are several factors related to eating disorders and their treatment that might lead to a relapse, including the severity of the illness, the presence of co-occurring conditions, and the need for higher levels of care. “Essentially, the more severe your eating disorder, the more likely you are to experience a relapse.”

But just because relapses are a reality for many, they aren’t a reason to avoid recovery altogether or to give up hope. By learning the common telltale signs and symptoms of a relapse, you can help minimize the impact it has on your long-term health and happiness and get back on track as soon as possible. Here’s how.

What causes eating disorder relapses?

While there are many aspects that may contribute to the ultimate success of eating disorder treatment, two important considerations, according to research, are adequate weight restoration when necessary, and the cessation of disordered behaviors. “Several studies have found that not gaining enough weight during treatment or continuing to experience regular eating disorder symptoms—e.g., compulsive exercise, or food avoidance—can lead to a higher likelihood of relapse,” Menzel says. “Eating disorder relapses can also be triggered by the same things that brought them on in the first place, like major life stressors including a traumatic event, a loss, or an acute illness.”

Menzel believes that by understanding your own triggers (or those of a loved one in recovery), you can help prevent a relapse or at least reduce its detrimental effects. Creating a “relapse prevention plan” is an important strategy to identify risk factors for a relapse.

Part of your relapse prevention place could mean:

- Knowing the initial signs or symptoms to watch out for

- Connecting with support systems

- Calling on coping skills

- Understanding when a return to treatment is necessary

Menzel also advises patients and their families to be mindful of the non-linear nature of recovery—and to learn to accept apparent slip-ups. “It’s important to differentiate between what I call a ‘blip’ and a full blown ‘relapse.’”

Menzel categorizes a ‘blip’ as a temporary period during which eating disorder thoughts, urges, or negative emotions may become stronger or more frequent, and some behaviors may even return, for a short time. “During blips, you’re able to use skills and lean on your support system to ride them out and get yourself back on track with recovery.”

During a relapse, on the other hand, “Those thoughts, urges, emotions, and behaviors have intensified and gone on long enough that they are starting to significantly impact your physical and emotional well-being again,” says Menzel.

The most common telltale signs of an eating disorder relapse

While every person and situation is unique and the presentation of relapses can vary as much as the eating disorders themselves, Menzel says these are some common warning signs to be aware of:

- Weight loss: “For many people recovered from an eating disorder, weight loss is a common sign of relapse. Even a little bit of weight loss can quickly cause eating disorder thoughts and urges to intensify, causing a snowball effect that leads to further weight loss.”

- Not finishing meals: “While it's perfectly normal not to finish a meal from time to time, this could be a slippery slope for someone with an eating disorder. It’s easy to rationalize that it ‘doesn’t matter,’ but an eating disorder relapse often starts with these kinds of small acts of restriction that can quickly become more common and lead to further restriction.”

- Weighing: “Weighing can be a sign of increased concern or investment in your weight or body image—things that increase the importance of your appearance and lessen the importance of other valued areas in life.”

- Worsening mood or anxiety: “For many patients that I’ve worked with, the first sign of a possible relapse were changes in their mood or anxiety. They were more irritable, more inflexible, or down—and it was almost always accompanied by weight loss, a sure sign that they had started to restrict again.”

- Eating alone or in secret: “Finding reasons not to eat with others or preferring to eat certain foods or meals alone may be another sign of relapse. Feeling shame around eating or what you eat is most certainly caused by the eating disorder.”

- A growing list of restricted foods: “Finding reasons to avoid eating specific foods that you used to eat could also lead to a relapse. Maybe you’re sticking to safe foods or avoiding a type of food for health or body image reasons. Starting to exclude foods from your diet, though, could definitely become cause for concern.”

What to do if you or someone you love might be experiencing a relapse

If a relapse does appear to be on the horizon or is already occurring, returning to the early steps of recovery and reaching out for support can make a significant impact on recovery. “Go back to basics and lean on your support system,” Menzel says. “Eating disorders thrive in isolation. Letting in someone from your trusted support network can give you the strength you need to start making changes.” Many people find it helpful to return to the basics they learned in treatment, like:

- Regular eating

- Increased accountability or supervision

- Self-monitoring

- Using coping skills

- Meeting regularly with your treatment team

Oftentimes a return to formal treatment is necessary, at least for a period of time. Having a dedicated care team providing guidance can help you through a relapse and help you start to reduce disordered behaviors again. Virtual eating disorder platforms like Equip make it possible to get support for a relapse without uprooting your life. Reaching out for consultations can also help you determine if it’s time to return to a form of treatment.

The most important thing to keep in mind is that relapses are not a sign of weakness or an inability to fully recover—they are a normal, common part of the recovery process (learn more about why they are so common here.) Accepting the possibility of relapses and maintaining a set of coping strategies will go a long way in mitigating their impact.

“Sometimes we have this expectation that being ‘recovered’ means that you’ll never have another eating disorder urge, or you’ll never have intense, negative emotions,” Menzel says. “And that’s just not realistic—we all have times in life where we have thoughts, urges, and emotions that are unpleasant, unhelpful, or uncomfortable. We all have times where we struggle and are not at our best. Recovery is not perfection. What matters most is not whether you have these thoughts and urges, but rather how you respond to them.”

- Berends, Tamara, Nynke Boonstra, et a;. 2018. “Relapse in Anorexia Nervosa.” Current Opinion in Psychiatry 31 (6): 445–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/yco.0000000000000453.

- Carter, Jacqueline C., Kimberley B. Mercer-Lynn, et al. 2012. “A Prospective Study of Predictors of Relapse in Anorexia Nervosa: Implications for Relapse Prevention.” Psychiatry Research 200 (2-3): 518–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.04.037.

- Rozakou-Soumalia, et al. 2022. “BMI at Discharge from Treatment Predicts Relapse in Anorexia Nervosa: A Systematic Scoping Review.” Journal of Personalized Medicine 12 (5): 836. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12050836.

- Miskovic-Wheatley, Jane, Emma Bryant, et al 2023. “Eating Disorder Outcomes: Findings from a Rapid Review of over a Decade of Research.” Journal of Eating Disorders 11 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00801-3.

- Sala, Margaret, Ani Keshishian, et al. 2023. “Predictors of Relapse in Eating Disorders: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Psychiatric Research 158 (February): 281–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.01.002.