- Research shows that virtual eating disorder treatment is as effective as in-person care.

- Virtual care offers unique benefits, like more flexibility, the ability to include loved ones, and the chance to build skills in real-life.

- For patients who are medically stable, virtual treatment is an appropriate choice. Most programs can adjust the intensity of treatment to a patient's needs.

Considering eating disorder treatment for yourself or your loved one can be overwhelming. You might be uncertain about which level of care you need or who should be part of the treatment team. Depending on where you live, you could struggle to find experienced providers within a reasonable distance. And of course, you have to consider all this alongside the cost and time involved.

One option that could ease your anxiety is virtual eating disorder treatment. This type of care can be more accessible and just as impactful (if not more so) than traditional in-person treatment.

“Not having to leave home—or school, the office, whatever—to access medical, therapeutic, and nutrition support and skill-building is a game changer,” says Equip’s Director of Lived Experience, JD Ouellette. "No longer is a one-hour appointment actually three hours with driving included. No longer is it a logistical impossibility to get multiple family members to be able to participate in sessions at an appointed hour. No longer is it necessary to access a residential or partial hospitalization program for coordinated team care.”

Read on to learn more about virtual eating disorder treatment, including what the current evidence says about it and how to decide if it’s the right fit for you or your loved one.

How effective is virtual eating disorder treatment? What the research shows

“The research is clear that virtual care is as effective as in-person care and has benefits that make it easier to access,” Ouellette says.

To point to one example, in a study published this year in the Journal of Medical Internet Research, patients who received virtual intensive outpatient (IOP) treatment had similar improvements in eating disorder symptoms as patients who received in-person IOP care. Additionally, the virtual group had greater improvements in depression scores and suicidal ideation and reported higher satisfaction, likely due to the convenience. The researchers concluded that virtual care improves access to treatment without sacrificing quality.

Importantly, research shows that virtual eating disorder treatment isn’t just an alternative to lower levels of care, like IOP. According to a study of 109 adults published in the International Journal of Eating Disorders in 2024, patients who received virtual day treatment and those attending in-person day treatment (such as a partial hospitalization program, or PHP) both reduced disordered eating attitudes and behaviors and gained weight.

And earlier research published by Equip researchers in Eating Disorders: The Journal of Treatment & Prevention found that not only does virtual eating disorder treatment work, it’s just as effective as traditional treatment. After 16 weeks of treatment, 80 percent of patients with weight restoration goals achieved their weight goals, eating disorder symptoms were reduced by half, and symptoms of depression and anxiety lessened by a third.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, virtual treatment became the default out of necessity, and the shift was somewhat haphazard in some instances. But after seeing the promising results of virtual care, many treatment providers began deliberately structuring care to work in a remote environment, leading to even better outcomes. A 2025 peer-reviewed “intentionally remote” program helped patients of all ages reduce eating disorder and depressive symptoms, gain weight, and improve their quality of life. (Equip treatment is a pioneer of treatment that is “virtual design,” offering an approach that fully leverages all of the advantages of remote care.)

All of this evidence underscores the fact that families can recover in the comfort of their home, which also offers added benefits, Ouellette says: “A recovery that happens at home, and in one's life, has significant staying power over one that can only be achieved and maintained in an artificial environment.”

Who virtual care works best for

Although virtual eating disorder care is proven to be effective, it's not the best option for everyone. Here's a look at which patients typically are and aren't a good fit.

Virtual care works best for patients who:

- Are medically stable

- Have the capacity to engage virtually

- Have caregiver support (for minors)

- Benefit from home-based exposures and flexible scheduling

Patients may need to pursue in-person treatment (at least temporarily) if they fit any of the following criteria:

- Medical instability (abnormal vitals, electrolyte abnormalities, syncope, EKG changes)

- Acute suicidality or self-harm risk

- Need for 24/7 monitoring and/or hospital refeeding

The bottom line is that in the majority of cases, virtual care is an appropriate and effective eating disorder treatment option. And when patients require in-person care due to certain risk factors (like having medical instability or exhibiting suicidality), they can generally transition to virtual treatment once those acute issues have been addressed.

Virtual vs. in-person: Pros, cons, and outcomes

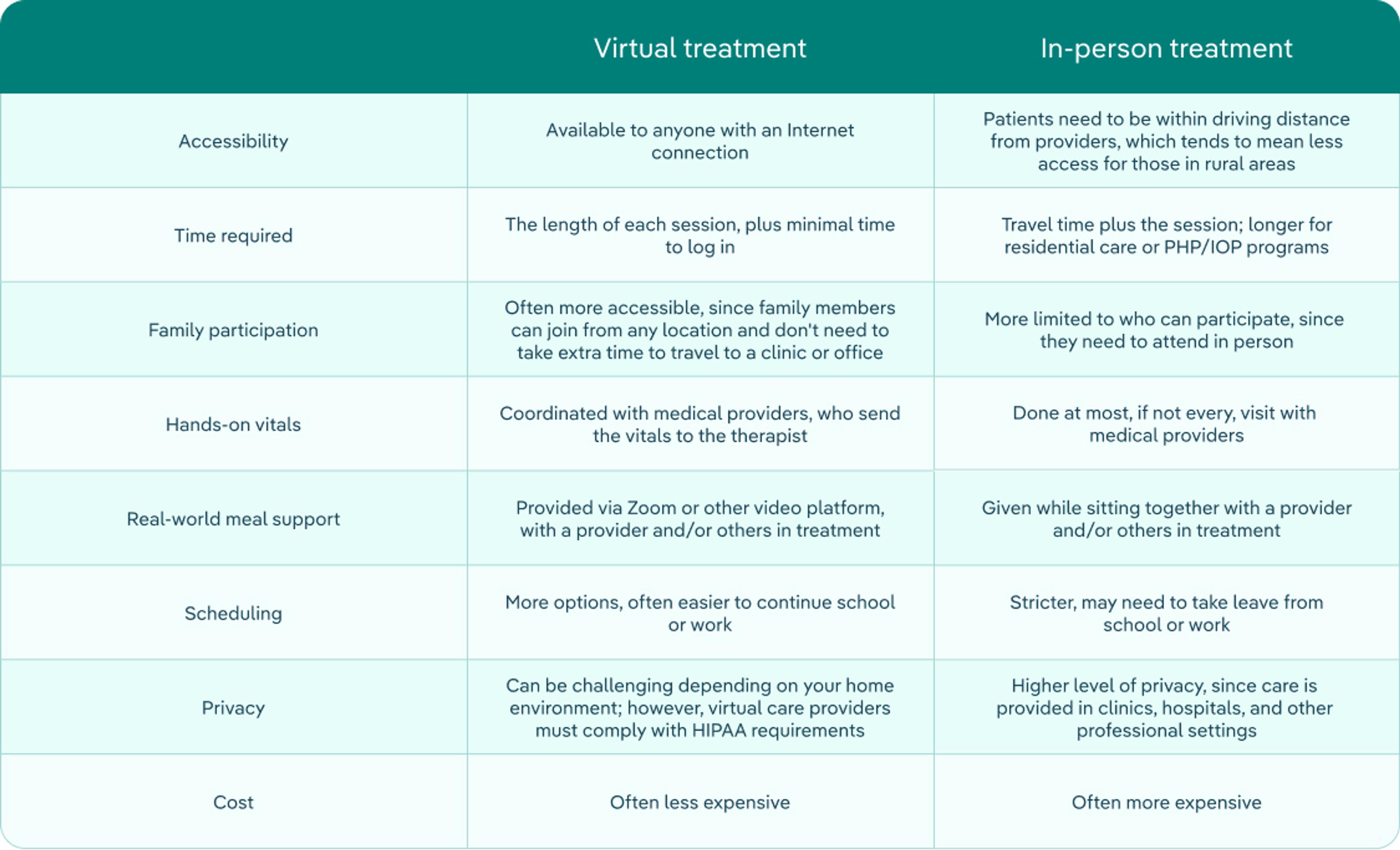

Both virtual eating disorder treatment and in-person eating disorder treatment have advantages and disadvantages. This table can help you compare the two. (Keep in mind: every program is unique; this is a general comparison.)

In the end, both types of care can be effective. You need to make the best choice for you or your family based on a number of different factors, including medical safety, level of structure needed, and life logistics.

That said, given its accessibility, remote eating disorder treatment can be a life-saving option for those who may not otherwise be able to obtain care. It also comes with the significant benefit of allowing people to recover in their day-to-day life—rather than a clinical setting—which can help them build real-world skills and coping strategies that protect against relapse.

Virtual treatment can also adapt to be equivalent to different levels of care (including IOP and partial hospitalization program, or PHP) based on patient needs. The intensity of sessions titrates up or down depending on individual needs and progression toward recovery. This may mean more or less frequent sessions, and it's the same thing that would happen if you attended an in-person program. Licensed clinical psychologist Jessica L. Van Huysse, PhD, explains that in certain cases, a patient who starts with virtual care but needs more structure or support might change to in-person sessions and then step back down to virtual treatment when appropriate.

At Equip, our virtual treatment incorporates multiple evidence-based modalities proven to lead to recovery in those with eating disorders. We pull from these different approaches to tailor treatment to each patient and their support network, and use a multidisciplinary care team to provide wraparound care that mimics more intensive in-person care. Our treatment model is proven to work; and, conveniently for patients and their families, the place where that model happens is your own home.

Virtual treatment for kids & teens (including ARFID)

Virtual treatment works for patients of all ages. For children, adolescents, and young adults, family-based treatment (FBT) is the gold standard treatment for eating disorders. And because FBT is based on the idea that healthy family members should take the central role in their child’s recovery, it doesn’t just work when delivered virtually—it needs to be delivered virtually in order to be effective.

“When patients are able to continue their care in their home environment, it helps families be integrated throughout the treatment process if they're using family-based treatment,” says Van Huysse. “Virtual treatment helps the caregivers know how best to support their child, rather than having a disconnect where the child goes somewhere to stay for a few months for treatment, and then they come home and the family is not equipped with the same skills that the adolescent was learning while at treatment. And the patient can practice things that come up in their home environment with the support of their treatment team, versus not having to navigate those challenges until they come home and are on their own. This helps recovery be more sustainable.”

In FBT, often the entire family joins weekly virtual sessions as well as group therapy. The focus is on empowering parents or other caregivers to take the lead in helping renourish their child. FBT allows families to build a recovery-supporting environment at home, and the patient to learn to use recovery skills in real life.

Studies show that virtual FBT leads to weight restoration and reductions in eating disorder behaviors and thoughts, depression, anxiety, and caregiver burden. It also results in similar outcomes as in-person PHP, according to a study published in the International Journal of Eating Disorders in 2022.

Additionally, research shows that telehealth delivery of leading treatments for avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID, which is most commonly seen in kids) can be effective. In a study published this year in the International Journal of Eating Disorders, Equip provided virtual cognitive behavioral therapy for ARFID (CBT‐AR) or virtual family‐based treatment for ARFID (FBT‐ARFID) to almost 800 youth and adults. Both therapies led to weight gain for those who needed it; improvement in ARFID, anxiety, and depression symptoms; and increased willingness to try new foods.

How to evaluate a virtual program

When considering virtual eating disorder treatment programs, it’s important to make sure it meets certain criteria. The checklist below provides a good overview of the factors you should consider when deciding on a virtual provider.

What to look for in a program:

- Evidence-based care: FBT, CBT-E, DBT and/or ERP

- Multidisciplinary team: Medical, therapist, dietitian, peer/family support

- Published outcomes or ongoing quality metrics

- Medical monitoring plan: Vitals, labs coordination

- Family involvement (for youth) and/or caregiver coaching

- Insurance and coverage transparency

- Licensure by state

- Waitlist status and start timelines

- Safety and privacy practices, including HIPAA and secure platforms

- Age and diagnosis fit

Testimonials and reviews can also be extremely helpful and important when it comes to choosing a program. Hearing what the experience was like for others in similar situations provides a different perspective that can help you assess whether the program is right for you. However, it’s important to prioritize patient outcomes and clinical fit over star ratings, which can be subjective.

Costs, insurance, and access

As with any eating disorders treatment, the cost of care and whether insurance covers telehealth varies from program to program and insurance plan to insurance plan.

Still, virtual care can reduce non-medical costs (like travel and time), and generally has a much lower price tag than in-person care if you are not covered and choose to pay privately. Equip accepts most major insurance plans, and offers zero interest payment plans to make any out-of-pocket costs more affordable. You can check your Equip coverage through our insurance screener. When you schedule a consultation, we’ll also verify that you’re in-network and verify the details of your coverage.

Benefits of virtual care

While many people still think of in-person care as the go-to model for effective treatment, there are some distinct advantages to going the virtual route. Some of these factors can make or break a patient's ability to initiate and maintain participation in evidence-based care:

- A lower time commitment, as there is no need to commute to appointments

- More flexible scheduling, allowing sessions to fit into school or work schedules

- Less stress around the logistical challenges of accessing treatment

- Ease of accessing items for specific therapy interventions (i.e., items for family meals or exposure therapies)

- Ability to have multiple family members join from different locations

- Access to providers experienced and trained in evidenced-based modalities

- Ability to learn and practice skills in real life, rather than recovering in a “treatment bubble”

For patients who are medically stable, Van Huysse recommends exploring virtual treatment. “It tends to be just as effective as in-person care,” she says. “Some people worry about what it will feel like connecting with a therapist virtually versus in person. But if they're willing to give it a try, oftentimes people find it goes better than anticipated.”

For those still on the fence, Ouellette suggests first considering any specific reservations about the path and then evaluating each concern one by one. “Oftentimes whatever challenges there are can be mitigated with some creative thinking and planning,” she says. “Aside from deciding between virtual and in-person care, it's most important to define the treatment model you want to use and the evidence that supports its use, and go from there. A lot of people click with this when I say, 'Residential treatment is a place not a treatment model; oncologists don't prescribe an infusion center, they prescribe a specific chemotherapy protocol that is available at infusion centers.'"

Getting ready for virtual sessions: privacy, tech, and setup

If, after reading all of this and comparing your options, you choose virtual care for an eating disorder, congratulations! Just by making that choice, you've taken the next step toward recovery. To help your sessions go as smoothly as possible and set you up for success with virtual treatment, follow these tips:

- Create a quiet, private space. Think beyond your bedroom. A closet, bathroom, or even a parked car works. If you’re a parent or caregiver of a child, consider having separate locations for your child and any adults involved in treatment, as the therapist may want to speak with each of you individually at some point during appointments.

- Check your device. Test your internet connection, camera, microphone, and speakers or headphones before sessions.

- Ask how your provider would like to coordinate weigh-ins. They may ask you to have a family member assist with a blind weight, have you position the scale so they can see it but you don't look, or something else. In some cases, you may need to make an in-person appointment with an external provider, who can send your weight and vitals to your virtual team.

- For meal support, set up the camera so the other person(s) can see your face and your plate.

- Keep any comfort items nearby to use if emotions become intense.

- Have a backup plan. If your internet drops or your screen freezes, try immediately to reconnect. If you can't, see if it's appropriate to switch to the phone or reschedule. Be sure you have your provider's number (or another way to contact them) and discuss ahead of time how you’ll reach out if you lose them over video.

FAQ

Is virtual IOP as effective as in-person?

Yes, virtual IOP is as effective as in-person care and leads to similar eating disorder symptom improvements, according to research. Some studies also show that telehealth programs result in greater reductions in depression scores and suicidal ideation and higher levels of satisfaction.

Can virtual care treat all types of eating disorders—anorexia, bulimia, BED, ARFID?

Yes, virtual care has shown to be effective for most eating disorders, including anorexia and bulimia. Evidence for binge eating disorder (BED) and ARFID are promising. No matter the diagnosis, the key is to choose a program that provides the necessary level of care and ensures medical monitoring so the intensity of treatment can be adjusted if necessary.

How do virtual programs check medical safety?

For patients who need medical monitoring, most virtual eating disorder programs have patients visit their local primary care provider on a regular basis to have their vitals checked and any other tests done to confirm medical safety. Then that provider sends the patient's results to the virtual care team via a secure portal.

How quickly can we start?

How quickly someone can start virtual eating disorder treatment varies. You may need prior authorization, and in general it's smart to confirm with your insurance provider that the program is in network and what your copays will be. The program may also put you on a waitlist until space opens up. In that case, ask them about interim supports they offer or can refer you to.

At Equip, there is no waitlist, and our admissions team confirms coverage and any out-of-pocket costs on your behalf. Generally, patients begin treatment within two weeks of their initial outreach.

Does insurance cover virtual treatment?

Many major health insurance companies cover virtual eating disorder treatment. However, coverage varies from plan to plan and may also be state specific. Before you enroll in a program, call your insurance member services to verify your benefits, if you need prior authorization, and if the program you're interested in is in network.

What if my child denies a problem or refuses treatment?

If your child or loved one denies a problem or refuses eating disorder treatment, don't give up. Rather than ultimatums or pressure, be compassionate. Express your concern using “I” statements, telling them what you've noticed and how that makes you feel. At the same time, validate their feelings and how hard this must be for them. Then listen without judgment. It may take several conversations, but don't give up. You may also have to use your leverage as a parent to make sure they receive the treatment they need, Van Huysse says. “If your child had a medical diagnosis and was refusing to go to appointments or take their medication, what would you do?” she asks. You may need to say, 'you have to do this,' in a firm but loving way.

- Blalock, Dan V, et al. “Virtual Versus In-Person Intensive Outpatient Treatment for Eating Disorders During the COVID-19 Pandemic in United States–Based Treatment Facilities: Naturalistic Study.” Journal of Medical Internet Research. Vol. 27 (2025:e66465. doi:10.2196/66465

- Thaler, Lea, et al. “Outcomes of a Virtual Day Treatment Program for Adults With Eating Disorders-Comparison With In-Person Day Treatment.” International Journal of Eating Disorders vol. 57,10 (2024):2135-2140. doi:10.1002/eat.24263

- Steinberg, Dori, et al. “Effectiveness of delivering evidence-based eating disorder treatment via telemedicine for children, adolescents, and youth.” Eating Disorders vol. 31,1 (2023):85-101. doi:10.1080/10640266.2022.2076334

- Shepherd, Caitlin B, et al. “From stopgap to opportunity: outcomes across age groups in an intentionally designed, remote eating disorder treatment program.” Eating Disorders vol. 22 (2025):22:1-17. doi:10.1080/10640266.2025.2534803

- Van Huysse, Jessica L, et al. “Adolescent eating disorder treatment outcomes of an in‐person partial hospital program versus a virtual intensive outpatient program.” International Journal of Eating Disorders vol. 56,1 (2022):192–202. doi:10.1002/eat.23866

- Hellner, Megan, et al. “Clinical Outcomes in a Large Sample of Youth and Adult Patients Receiving Virtual Evidence-Based Treatment for ARFID: A Naturalistic Study.” International Journal of Eating Disorders vol. 58,4 (2025):680–689. doi:10.1002/eat.24355

- Mitchell, James E, et al. “A randomized trial comparing the efficacy of cognitive–behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa delivered via telemedicine versus face-to-face.” Behaviour Research and Therapy vol. 46,5 (2008):581–592. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2008.02.004

- Shepherd, Caitlin B, et al. “Outcomes for binge eating disorder in a remote weight-inclusive treatment program: a case report.” Journal of Eating Disorders vol. 11 (2023):80. doi:10.1186/s40337-023-00804-0