- Athletes have an increased risk of eating disorders due to factors such as perfectionism, body comparisons, gym culture, and pressure to maintain a certain look or weight.

- Eating disorders put an athlete’s sport and health at risk. They can cause heart issues, injuries, fatigue, slow recovery, and mental burnout if not addressed.

- Recovery from an eating disorder starts with early intervention followed by treatment from an expert team of professionals such as Equip’s virtual eating disorder treatment.

Olympic figure skater Gabrielle Daleman is all too familiar with eating disorders in athletes. The two-time Olympic competitor won gold with team Canada during a team figure skating event at the 2018 Olympics. But in 2019 she took a step back from her career to address her mental health and eating disorder.

Daleman said her eating disorder started when she was in 6th grade, and that figure skating’s expectations contributed to her symptoms.

“I just grew up in a very strict sport,” Daleman said. “It's not only strict with what we physically have to do, but it's a judged sport, and we're also judged on our appearance.”

Daleman, who is also a 2017 world bronze medal winner, is currently in eating disorder recovery. And she shared that it’s possible for other athletes to get to recovery too, even though the journey can be hard.

“A lot of times when you go through this, you feel very alone, very isolated, and like you're never going to be able to get out of the rabbit hole. You are,” Daleman said. “It gets better.”

Daleman’s experience with an eating disorder is common among athletes. In this article, we’ll explore why athletes are at increased risk for eating disorders, how to recognize the signs of eating disorders in sports, and what recovery looks like.

How common are eating disorders among athletes?

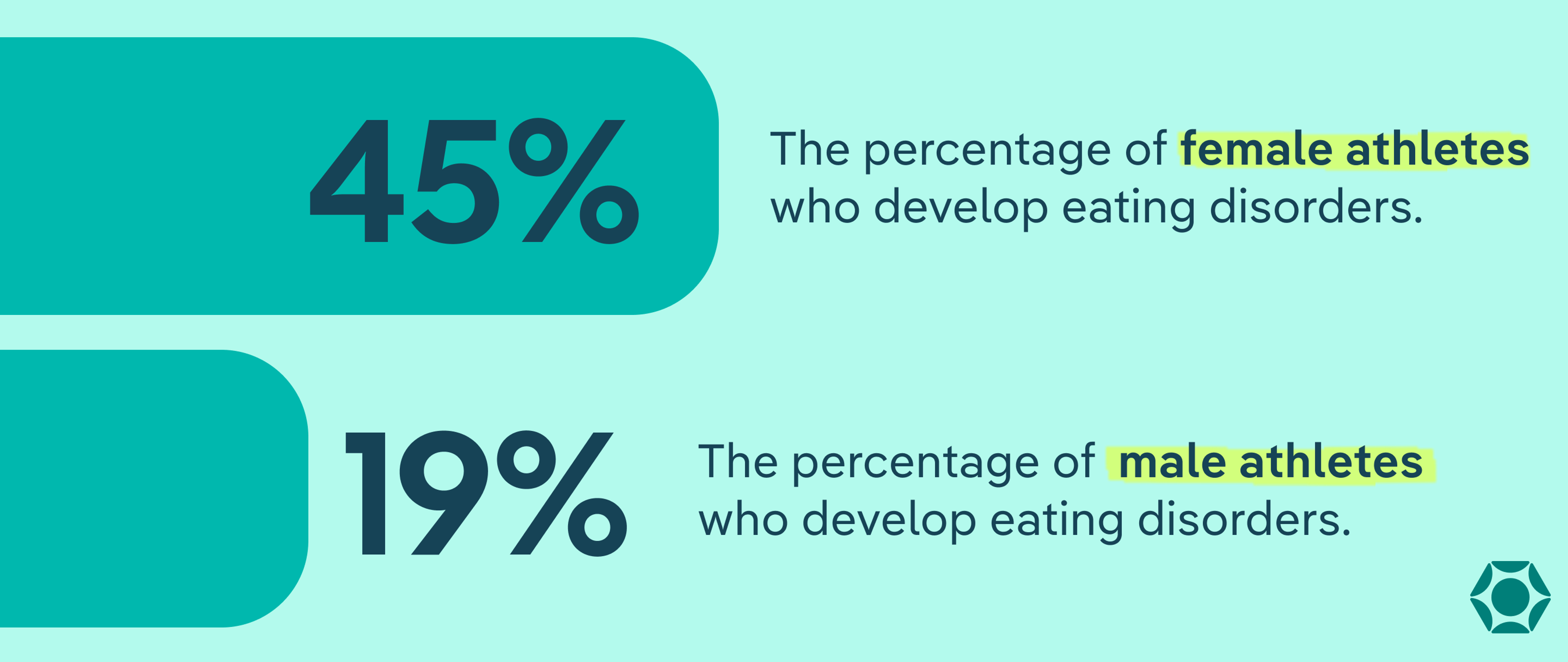

Sports and eating disorders often go hand in hand. Eating disorders in female athletes are more commonly diagnosed than eating disorders in male athletes. But athletes of all genders can develop an eating disorder.

- Up to 45% of female athletes and 19% of male athletes develop eating disorders.

- Young athletes are up to three times more likely to have an eating disorder compared to their nonathletic peers.

- Nearly 46% of athletes in weight-sensitive sports like gymnastics, wrestling, and swimming have an eating disorder, compared to about 20% in non-weight sensitive sports (which is still higher than the risk for non-athletes).

- An estimated 12% of female athletes and 6% of male athletes have disordered eating patterns.

Athletes may develop any type of eating disorder, including anorexia, bulimia, or binge eating disorder. But the two most common EDs among athletes that Amy Goldsmith RDN, LDN, owner of Kindred Nutrition & Kinetics, sees in her practice are anorexia and bulimia.

Those with anorexia severely restrict their food and have an intense fear of gaining weight. Athletes may eat far fewer calories than their body needs while also having a distorted view of their body size or shape. Athletes may also develop anorexia athletica. Although not an official eating disorder diagnosis, anorexia athletica includes severe calorie restriction along with compulsive exercise.

Bulimia is an eating disorder where someone consumes a lot of food and then try to “get rid of” or “make up for” it by purging. Purging can take many different forms, but common purging behaviors are self-induced vomiting and laxative misuse. In athletes, Goldsmith says, purging may look like excessive exercise to compensate for calories eaten.

Why are athletes at higher risk for eating disorders?

Athletes are at higher risk for an eating disorder due to a number of factors. These range from sport-specific influences to things that can happen in someone’s personal life.

Sport-related factors

- Gym culture: Toxic gym culture is very rigid, which can contribute to eating disorder behaviors. It encourages restrictive eating habits, excessive exercise, perfectionism, and comparisons.

- Seeing disordered patterns in teammates: Noticing disordered eating or compulsive exercise in other teammates can also trigger an eating disorder. Plus, disordered patterns like excessive exercise or being overly rigid about food can often be normalized/praised in athletic contexts as "discipline" or "dedication."

- Injuries: “When my athletes have an injury, there is a feeling of a loss of control,” Goldsmith said. As a result, an athlete may instead turn to what they can control, which is the way they look and what they do with their body.

- Pressure to maintain a certain body shape or weight: Depending on the sport, someone may be pressured to look a certain way or weigh a certain amount, which encourages disordered eating.

- Body comparison: Body comparisons can lead to food restriction or compulsive exercise to try and “measure up” to other athletes.

- Starting a sport early: Specializing in a single sport early in life increases someone’s risk for developing an eating disorder. This may be due to the pressure to maintain a specific look or weight for your sport early on.

- Playing an individual vs. team sport: Athletes who participate in individual sports are more likely to develop an eating disorder compared to those who play a team sport. Those who play an individual sport may be more likely to work extra hard to be thin and be more dissatisfied with their body.

Personal factors

- Perfectionism: Athletes are high performers, but perfectionism can sometimes push someone into eating disorder behaviors. “[Perfectionism] can lead to counting your calories or your macros or looking at your weight every day, which can perpetuate rumination and create that eating disorder,” Goldsmith said. In addition, athletes often receive praise and validation for their hard work, which plays into perfectionism and further encourages disordered eating and exercise patterns.

- Negative energy balance: Sometimes, an athlete may unintentionally be under-eating and have a negative energy balance, where they burn more calories than they need to consume. Being in a negative energy balance is often the triggering even that “turns on” an eating disorder in someone who is vulnerable to developing one.

Societal factors

- Comments about someone’s body: It’s not uncommon for athletes to hear comments about their body size, shape, or weight. These comments may encourage an athlete to try and change the shape of their body through disordered eating or excessive exercise.

- Diet culture: Athletes aren’t immune from the wider diet culture in our society. Diet culture places higher value on thin bodies and restrictive diets to try and achieve those body sizes.

- Misinformation about foods: Athletes may get misinformation about what they need to eat. “The sports and fitness industry teaches improper nutritional behaviors to athletes,” said Stephanie Kile MS, RDN, lead registered dietitian nutritionist at Equip. As a result, athletes may not be fueling their bodies correctly, which can lead to disordered eating.

Other factors

Like anyone else, athletes may be at risk for an eating disorder due to things that happen outside their sport. This includes stressors like low self-esteem, family problems, a family history of eating disorders, physical or sexual abuse, depression, or internalizing distress.

The role of sports culture and performance pressure

“Athletes are often praised for being ‘driven’ with long workout hours or pushing themselves or for being disciplined with their nutrition,” Goldsmith said. This performance pressure is especially felt in weight-sensitive sports.

Weight-sensitive sports (also known as “lean” sports) place value on aesthetics (how an athlete looks), weight, or endurance. Examples of weight-sensitive sports include:

- Wrestling

- Cycling

- Gymnastics

- Diving

- Swimming

- Body building

- Running

- Figure skating

- Dance

- Rowing

Although athletes who play these types of sports are more likely to develop an eating disorder, likely in part because of the extra pressure they experience, all athletes are at increased risk.

The connection between fueling, energy, and RED-S

Not all undereating in athletes starts as intentional—in some cases, they might be underfueling after workouts without knowing it. But even when it’s unintentional, this can lead to a serious health condition called relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S). RED-S is when someone’s body regularly does not have enough calories to fuel all of its daily functions. An estimated 63% of athletes are at risk for RED-S.

Common RED-S symptoms include:

- Fatigue

- Loss of endurance

- Decreased muscle strength

- Increased injuries

- Impaired judgement

- Lack of coordination

- Difficulty concentrating

- Lower agility

- Missing training due to sickness

- Depression

- Hormone disruptions

- Slow heart rate

- Low sex drive

- Menstruation irregularities

RED-S used to be called the female athlete triad, which included only three symptoms: irregular menstruation, loss of bone density, and low energy availability. However, the International Olympic Committee changed the term to RED-S in 2014 to be more inclusive. Now RED-S covers all genders as well as a wider range of the health consequences that come along with it.

Not all people with RED-S have an eating disorder, and vice versa. But there’s a strong overlap in the symptoms, and RED-S “can trigger a full eating disorder,” Goldsmith says, as being in a negative energy balance plays a role in eating disorder development.

What are signs of eating disorders in athletes?

Signs of an eating disorder among athletes include physical, behavioral, and emotional symptoms.

Physical signs

Common physical signs of an eating disorder in athletes include:

- Fatigue

- Inability to recover quickly

- Increased injuries, including stress fractures

- Loss of periods (amenorrhea)

- Changes in weight

- Dizziness

- Weakness

- Fainting

- Getting cold easily

- Sweating or hot flashes

- Chest pain

- Slow heart rate

- Swelling

- Shortness of breath

- Digestive issues like nausea and vomiting

- Low sex drive

- Low blood sugar (hypoglycemia)

- Disrupted sleep cycles

- Lanugo hair (fine hair that grows on the face and body)

- Dry hair

- Brittle nails

It’s important to note that some of these symptoms, like loss of a period or a slow heart rate, are sometimes considered “normal” for high-performing athletes. But experts caution against completely dismissing these potential red flags, as they could point to an eating disorder or RED-S. “You're definitely not eating enough if you have a low heart rate,” Goldsmith said.

Behavioral signs

Behavioral signs that could mean an athlete has an eating disorder include:

- Isolating more than usual

- Delayed reaction time

- Slower decision making

- Making more errors in their sport

- Skipping meals

- Rigid diet rules

- Not eating with teammates

- Difficulty concentrating

- Compulsive exercise

- Trouble taking days off

- Preoccupation with what other people are eating

- Removing food groups from their diet

Emotional signs

Eating disorders can also affect an athlete’s mental health and lead to symptoms such as:

- Mood changes

- Irritability

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Impatience

- Getting easily frustrated after practice or a competition

- Perfectionism

- Rigid thoughts around food intake and training

If you’re concerned for yourself, someone on your team, or a loved one, take Equip’s eating disorder screening quiz to better assess eating disorder risk.

How do eating disorders affect athletic performance?

Eating disorders in sports can have a major impact on an athlete’s short- and long-term performance. Here are some of the most common effects.

Fatigue

Athletes with low energy availability due to under-fueling are 2.5 times more likely to experience fatigue or decreased performance.

Slower recovery

Eating disorders among athletes lead to a slower recovery. Someone won’t “bounce back” quite as quickly after an intense workout or performance because their body doesn’t have the nutrition it needs.

Lack of concentration

Research suggests that when someone has an eating disorder, their cognitive ability—the ability to think clearly—can be reduced by as much as 40% during intense exercise.

Not being able to concentrate can negatively impact performance in a number of ways, like slowing reaction time and impairing coordination, both of, which can lead to more errors,.

Higher injury risk

Athletes with eating disorders are 4.5 times more likely to experience an injury—and take longer to recover. This includes fractures and overuse injuries. Compulsive exercise can also lead to muscle damage.

Getting sick more often

An athlete may end up missing out on practice more often, because eating disorders affect their immune system’s ability to fight off illness. As a result, they may be prone to getting colds or other infections.

Loss of bone density

Disordered eating can reduce bone density, which may cause stress fractures as well as osteoporosis. Osteoporosis causes bones to get thinner and weaker, also increasing someone’s risk of fractures.

Heart issues

Eating disorders can lead to a number of heart issues. If someone’s heart rate gets too low, they may experience fatigue, dizziness, and fainting. In severe cases, eating disorders can lead to heart attacks or heart failure.

Hormone changes

“If you're not eating enough or fueling enough, it will negatively affect hormones,” Goldsmith said. Disordered eating can disrupt an athlete’s levels of estrogen or testosterone. These hormones help build muscle, reduce risk of injury, and help with endurance.

Ghrelin, a hormone that helps us recognize hunger cues, can also be disrupted if someone has an eating disorder. This makes it difficult for that person to know when they’re hungry or when they feel full, Kile said.

Mental burnout

An eating disorder isn’t just a physical health problem. It also takes a toll on mental health and can lead to mental burnout. Mental burnout can cause a lack of focus or motivation and it can lead to exhaustion as well as dropping out of their sport entirely.

How to support an athlete who may be struggling

If you think an athlete may be struggling with an eating disorder, speak up right away. As hard as it may feel, “as soon as you notice something, you have to have that conversation,” Goldsmith said. “The longer that you walk on eggshells and you don't say anything, that strengthens the eating disorder.”

To approach the conversation, Goldsmith suggests leading with love and support, but “start with the facts” and “keep it unemotional.” Here’s some examples of how you can start the conversation:

- “I've noticed that you aren't recovering like you used to…”

- “It seems like you're more fatigued at practice. I'm wondering if it has anything to do with your nutrition…”

- “Do you feel like you fuel enough? Are you struggling with eating?”

- “How are you feeling from a body image standpoint?”

Once you’ve talked with your athlete, encourage them to seek professional help, especially if you’ve noticed:

- Weight loss or gain

- Decreased fluid intake

- Decreased food intake

- Fatigue

- Delay in decision making

“Symptoms that make someone suspicious of an eating disorder are just as concerning as someone limping from ankle pain, which would get checked out quickly,” said Goldsmith. The sooner an athlete gets into eating disorder treatment, the better.

“Early intervention is going to be able to prevent the bone issues, the injury, the fatigue, the nutritional deficiencies,” Goldsmith said. “You still have a decent amount of cognition where you're able to really receive the information and the education and move from there.” But regardless of how long it’s been going on, it’s still crucial to get help.

Keep in mind someone may need to pause participating in a sport for a time when they start recovery. While this may be hard, remember that eating disorder recovery will help athletic performance in the long run. An athlete in recovery will be more likely to avoid injuries and their body will be properly fueled for optimal performance when they return.

How Equip treats athletes

Equip offers comprehensive, personalized care for athletes with eating disorders. Equip’s approach takes into account the specific sport while also helping develop healthy fueling and exercise patterns. All of it can be done through virtual treatment in the convenience of an athlete’s home.

Equip’s treatment team includes sports experts who understand the unique pressures and consequences athletes with eating disorders face. “There are support groups, trained dietitians, and therapists to help navigate these complex situations,” said Kile.

Using the Staged Approach for Exercise Reintroduction (SAFER) protocol, Equip also helps athletes safely return to exercise and their sport when they’re ready. This is based on the Safe Exercise at Every Stage (SEES) guidelines, which were developed by experts in eating disorders, psychology, and sports nutrition. If an athlete is not able to leave their sport during treatment, Equip also has specialists who understand how to handle that situation too, added Kile.

The bottom line

Athletes are more likely than nonathletes to develop an eating disorder. This is due to the performance pressures athletes face, such as perfectionism, body comparisons, the need to maintain a certain look or weight, and gym culture. Eating disorders can cause a range of physical, behavioral, and emotional symptoms that include fatigue, low heart rate, loss of periods, avoiding certain foods, and depression. From slower recovery times to an increased risk of injury, eating disorders can have a major impact on an athlete’s performance.

So if you notice signs of an eating disorder in an athlete you care about, it’s important to have an open conversation. Start by stating the facts about what you’ve noticed and gently ask how they’re feeling about their fuel and body. Remember that eating disorder recovery is possible, especially with the help of specialized sports treatment teams like those at Equip.

FAQs

What are the three disorders of the female athlete triad?

The three disorders of the female athlete triad include irregular periods or loss of menstruation, bone density loss, and low energy availability.

Does wrestling cause eating disorders?

Wrestling doesn’t cause eating disorders, but wrestlers are at higher risk for developing one. Research suggests that wrestling has higher rates of eating disorders compared to other sports. This may be due to the fact wrestlers need to maintain a specific body weight to stay in their weight class. They also deal with body image pressures to look muscular.

Can athletes develop eating disorders even if they’re not trying to lose weight?

Yes, athletes can develop eating disorders, even if they’re not trying to lose weight. “Under-fueling a body can cause a cascade effect to kick in and can end up leading to an eating disorder due to imbalanced intakes, unintentional weight loss, and increasing risks for eating disorder thoughts,” said Kile.

Ackerman, Kathryn E, et al. “Low energy availability surrogates correlate with health and performance consequences of relative energy deficiency in sport.” British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 53, no. 10, 2 June 2018, pp. 628–633, https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-098958.

Alpay, Merve Rumeysa, et al. “Eating disorders and disordered eating on wrestling sport: A systematic review.” BMC Nutrition, vol. 11, no. 1, 24 Oct. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-025-01169-0.

“Athlete Burnout Paves the Way for Further Health Problems.” American Psychological Association, American Psychological Association, 23 Apr. 2025, www.apa.org/pubs/highlights/spotlight/athlete-burnout.

Bratland‐Sanda, Solfrid, and Jorunn Sundgot‐Borgen. “Eating disorders in athletes: Overview of prevalence, risk factors and recommendations for prevention and treatment.” European Journal of Sport Science, vol. 13, no. 5, 13 Nov. 2012, pp. 499–508, https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2012.740504.

Conviser, Jenny H., et al. “Assessment of athletes with eating disorders: Essentials for best practice.” Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, vol. 12, no. 4, 1 Dec. 2018, pp. 480–494, https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.2018-0012.

Currie, Alan. “Sport and eating disorders - understanding and managing the risks.” Asian Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 1, no. 2, 1 June 2010, https://doi.org/10.5812/asjsm.34864.

Delimaris, Ioannis. “Potential adverse biological effects of excessive exercise and overtraining among healthy individuals.” Acta Medica Martiniana, vol. 14, no. 3, 1 Dec. 2014, pp. 5–12, https://doi.org/10.1515/acm-2015-0001.

Dipla, Konstantina, et al. “Relative energy deficiency in sports (red-S): Elucidation of endocrine changes affecting the health of males and females.” Hormones, vol. 20, no. 1, 17 June 2020, pp. 35–47, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42000-020-00214-w.

Eating Disorders and Your Bones: Get the Facts, New York State Department of Health, www.health.ny.gov/publications/2049/index.htm. Accessed 15 Nov. 2025.

Eichstadt, Madison, et al. “Eating disorders in male athletes.” Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach, vol. 12, no. 4, 11 June 2020, pp. 327–333, https://doi.org/10.1177/1941738120928991.

El Ghoch, Marwan, et al. “Eating disorders, physical fitness and sport performance: A systematic review.” Nutrients, vol. 5, no. 12, 16 Dec. 2013, pp. 5140–5160, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5125140.

“The Female Athlete Health Report.” Project RED-S, Kyniska Advocacy, 2023, static1.squarespace.com/static/605d19d2a8f7856656d40fab/t/644a3ed2ab1dff42e83a9307/1682587351813/The+Female+Athlete+Report+2023.pdf.

Gallant, Tara L., et al. “Low energy availability and relative energy deficiency in sport: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Sports Medicine, vol. 55, no. 2, 1 Nov. 2024, pp. 325–339, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-024-02130-0.

Gorrell, Sasha, et al. “Eating behavior and reasons for exercise among competitive collegiate male athletes.” Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, vol. 26, no. 1, 28 Nov. 2019, pp. 75–83, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00819-0.

Ibáñez-Caparrós, Ana, et al. “Athletes with eating disorders: Analysis of their clinical characteristics, psychopathology and response to treatment.” Nutrients, vol. 15, no. 13, 30 June 2023, p. 3003, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15133003.

Magee, Meghan K., et al. “Body composition, energy availability, risk of eating disorder, and sport nutrition knowledge in young athletes.” Nutrients, vol. 15, no. 6, 21 Mar. 2023, p. 1502, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15061502.

Mancine, Ryley P., et al. “Prevalence of disordered eating in athletes categorized by emphasis on leanness and activity type – A systematic review.” Journal of Eating Disorders, vol. 8, no. 1, 29 Sept. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-020-00323-2.

Mountjoy, Margo, et al. “The IOC consensus statement: Beyond the female athlete triad—relative energy deficiency in sport (red-S).” British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 48, no. 7, 11 Mar. 2014, pp. 491–497, https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2014-093502.

Nazem, Taraneh Gharib, and Kathryn E. Ackerman. “The female athlete Triad.” Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach, vol. 4, no. 4, 21 Mar. 2012, pp. 302–311, https://doi.org/10.1177/1941738112439685.

Nickols, Riley. “Eating Disorders and Athletes.” National Eating Disorders Association, www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/eating-disorders-and-athletes-2/. Accessed 15 Nov. 2025.

Patel, Riti, et al. “Cardiovascular impact of eating disorders in adults: A single center experience and literature review.” Heart Views, vol. 16, no. 3, 2015, p. 88, https://doi.org/10.4103/1995-705x.164463.

Rosinska, Magda, et al. “Athletes with eating disorders: Clinical-psychopathological features and gender differences.” Journal of Eating Disorders, vol. 13, no. 1, 24 Feb. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-025-01221-1.

Sadek, Zahra, et al. “Exploring the prevalence and risks of eating disorders in Lebanon’s athletic community.” Scientific Reports, vol. 15, no. 1, 7 Mar. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85613-y.

“Safe Exercise at Every Stage.” SEES, www.safeexerciseateverystage.com/. Accessed 15 Nov. 2025.

Tenforde, Adam S., et al. “Association of the female athlete Triad risk assessment stratification to the development of bone stress injuries in collegiate athletes.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 45, no. 2, 30 Dec. 2016, pp. 302–310, https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546516676262.

Thackray, Alice E., and David J. Stensel. “The impact of acute exercise on appetite control: Current insights and future perspectives.” Appetite, vol. 186, July 2023, p. 106557, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2023.106557.

Torstveit, M. K., et al. “Prevalence of eating disorders and the predictive power of risk models in female elite athletes: A controlled study.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, vol. 18, no. 1, 9 May 2007, pp. 108–118, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2007.00657.x.