Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is an eating disorder, so ARFID treatment should be pretty similar to the treatment for anorexia or bulimia, right? Well, yes and no. First, every eating disorder manifests differently, so treatment is always individualized. Second, ARFID has some distinct characteristics that set it apart from other eating disorders, and treatment needs to address those unique aspects.

ARFID is an eating disorder characterized by eating a very small amount of food, a small variety of foods, or both. Some people may mistakenly think of ARFID as extreme picky eating, but it's not. Picky eating can be a common part of child development, whereas ARFID reflects a more persistent level of food avoidance that can cause many of the same health consequences as other eating disorders. Additionally, people with ARFID aren't just being picky: the term “picky” best captures someone with strong food preferences, whereas people with ARFID avoid certain foods because of sensory sensitivity, food-related anxiety, low appetite, or other underlying problems.

The prevalence of ARFID is still largely unknown. Studies estimate that anywhere between 0.3 to 15.5 percent of children and adolescents and 0.3 to 3.1 percent of adults have ARFID. But because ARFID typically doesn’t involve the same weight distress that characterizes other common eating disorders, many patients struggle to feel seen and understood.

Luckily, awareness about ARFID is increasing. The eating disorder was added to the The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 2013, legitimizing it as a mental illness. Since then, research to learn the intricacies of this diagnosis has rapidly expanded. However, this work has also exposed how few healthcare providers are aware of ARFID and able to identify it. This leaves many patients and families with questions about what ARFID treatment and recovery looks like, and how to get help. Here, we’ll take a look at how ARFID differs from other eating disorder diagnoses, and what to expect from treatment.

How is ARFID different from other eating disorders?

“The main thing that distinguishes ARFID from other eating disorders is that the disorder isn’t driven by concern about body weight or shape,” says Equip VP of Clinical Programs, Jessie Menzel, PhD. “Patients with ARFID often want to gain weight and are upset that they weigh so little or haven't grown. That doesn't mean that someone with ARFID can't experience body dissatisfaction, but body dissatisfaction is not the reason for their disordered eating.”

Reasons behind avoidant/restrictive eating

The causes of ARFID are complex. According to ongoing research, it appears that genetics, differences in hormones and brain function, and traumatic events, among other factors, may all play a role.

ARFID can present in one (or more) of three ways, all of which which contribute to a lack of food intake and variety:

- Low interest in food and low appetite: While people with anorexia may ignore their hunger cues, people with low appetite ARFID truly don't feel hungry very much. And when they do, they feel satisfied after eating a small amount of food.

- Selective eating due to sensory sensitivity: This type of ARFID is associated with intense aversions to or strong preferences for certain textures, colors, smells, and tastes. As a result, people eat a very limited number of “safe” foods.

- Avoiding foods because of a specific feared outcome: Fear of vomiting, choking, allergic reaction, pain, and illness can all keep some people from eating. Many times, this occurs after a traumatic eating-related event, or because of legitimate food allergies.

Negative consequences and risks

ARFID can have a significant negative impact on people’s physical health, mental health, and quality of life.

Physical risks include:

- Nutritional deficiencies

- Stunted growth

- Irregular or absent menstrual cycles

- Delayed puberty

- Osteoporosis

Psychological risks include:

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Low self-esteem

- Loneliness

- Guilt/shame

And, since food is central to social gatherings, ARFID can make everyday experiences—from school lunches to birthday parties to holiday meals—stressful. People with ARFID may feel anxious about what might be served or worry about others seeing their eating challenges or food choices. Often, they deal with this by avoiding these situations, even though that can leave them feeling isolated precisely when they need the most support. Vacations can also be incredibly difficult, because of the uncertainty of what food will be available. Overall, the food restrictions of ARFID limit a person's ability to live a full life.

Common misconceptions

1. ARFID is “just picky eating”

“ARFID includes extreme picky eating, but it also includes food phobias like fear of vomiting, choking, or having an allergic reaction. And it includes people who just aren't motivated to eat or interested in eating, period,” Menzel says.

2. ARFID only affects children

“While many people with ARFID can trace their eating problems back to childhood, ARFID can develop at any point, and there are many adults struggling with ARFID who need treatment,” Menzel says.

3. ARFID is about weight loss

People with ARFID often struggle to gain weight, but they're not purposely trying to lose weight. “ARFID captures a whole range of eating problems that aren't motivated by weight or shape,” Menzel says.

4. People can outgrow ARFID

ARFID is an eating disorder, not a phase—so it doesn't just go away on its own. Recovery requires specialized treatment and professional support. Early intervention helps, because the sooner you can begin treatment, the lower the risk of negative physical and mental health effects.

How is ARFID treatment different from other eating disorder treatment?

Every eating disorder—and every person—is different, so the specifics of treatment will vary depending on a patient’s particular needs and their presentation of ARFID. That said, a core component of treatment for ARFID is exposure, or helping a patient face and cope with anxiety-provoking or challenging foods and experiences, Menzel says. “While you can find exposure in treatment for other eating disorders, it is really a central focus in treatments for ARFID,” she adds.

“Exposures are meant to help you adjust to new, unfamiliar, or ‘unsafe’ foods with the goal of adding those foods to your diet,” she explains. “For example, dietitians may help patients make an ‘always/sometimes/never’ list of foods, and the goal of exposures is to move ‘never’ foods into the ‘sometimes’ or ‘always’ columns.”

The specific treatment modalities and approaches used for ARFID are also somewhat different from those used to treat other eating disorders.

Psychotherapy for ARFID

There are several therapy approaches used in ARFID treatment, including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), family-based treatment (FBT), and exposure and response prevention (ERP).

Cognitive behavioral therapy for ARFID (CBT-AR) works to challenge the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that are maintaining the eating disorder. The first step of CBT-AR is renourishment (if needed), when the focus is on eating meals and snacks regularly throughout the day. Next, the patient and their therapist work through modules designed to address whichever presentation(s) of ARFID the patient has: sensory sensitivity, fear of a negative outcome from eating, or a lack of interest in eating.

For example, for sensory sensitivity, the goal is to expand food variety preferences, which is often done through gradual, incremental taste tests followed by learning different strategies for incorporating that food into your diet. For example, if a child likes a certain brand of French fries, they might experiment with other brands, then homemade roasted potato wedges, and then mashed potatoes. Or they may try different seasonings or sauces to make new foods more likeable.

Exposure and response prevention is a specific type of CBT that can be particularly helpful in treating ARFID. It helps patients to overcome food avoidance that is driven by fear, such as fear of choking, fear of vomiting, fear of pain, or fear of allergic reaction. It can also help with other fears, like social events that involve eating in front of others, or eating food prepared by others. Therapy provides a safe space where patients are supported as they're gradually exposed to their different fear foods so they can become more comfortable with them.

Lastly, family-based treatment for ARFID (FBT-ARFID) is designed for children, adolescents, and teens who live at home. With FBT, specialized providers empower parents to take the reins in their child's recovery by giving them the skills and strategies needed to help their child renourish and stop engaging in food avoidance behaviors.

ARFID treatment for children vs. adults

Just as ARFID in children looks different than ARFID in adults, there will also be differences in the treatment approaches for these two populations.

What sets ARFID treatment for children apart from adult treatment is the involvement of parents (or other caregivers) and the use of reinforcement strategies. Parents play an essential role in a child's ARFID treatment. They provide structure for the child's eating schedule, help support the child during exposure exercises at home, foster a safe eating environment, and help the child manage food-related anxiety. They also practice positive modeling, showing their child how eating a variety of foods is enjoyable. For adults, on the other hand, treatment is generally self-driven.

Younger children may struggle to be motivated to engage in treatment. To them, their reasons for not eating make sense. Sometimes, reinforcement strategies (like reward systems) might be helpful to encourage engagement with treatment. Adult patients can also work with their therapist or dietitian to set up their own positive reinforcement strategies, but these will look quite different from the reward system a parent might use for a child with ARFID.

While not necessarily a component of treatment, it’s worth noting that children and adults will encounter different challenges and circumstances that need to be addressed during treatment. Children, for example, might need to contend with short and stressful school lunch periods, and growth and development is a concern. Adults, meanwhile, may be challenged by things like workplace meals, dating, or social life.

Treating comorbidities

With ARFID treatment, it's often important to target other conditions that can make eating harder. “Things like functional GI disorders, food allergies and sensitivities, or sensory processing disorders need to be addressed,” Menzel says. “It's important that we do everything we can to make eating an easier or less painful experience for a person with ARFID.”

Another important characteristic to consider in ARFID treatment is the potential overlap between ARFID and certain other diagnoses. Research has shown that individuals with autism spectrum conditions, ADHD, and other psychiatric disorders are much more likely to develop ARFID.“Other distinguishing traits could include higher sensory sensitivities or more intense anxiety,” explains Equip Peer Mentor Kelsey Gilchriest, who is in recovery from ARFID. If any of these conditions or issues are present, treatment should include interventions to address them with educated providers.

The key to recovery: ARFID treatment from experts who get it

Since not every healthcare provider is aware of ARFID—let alone familiar with it—it's essential to seek treatment from physicians and specialists who understand the depth and complexity of ARFID. It's also important to work with a multidisciplinary team that may include some or all of the following:

Licensed therapist

“Many people with ARFID are being treated solely in medical spaces: in feeding disorder clinics, gastroenterology, or with allergists,” Menzel says. “I often find that help from a therapist or psychiatrist is what's been missing from someone's treatment journey and can make a huge difference. And for children struggling with ARFID, a therapist can give support to the parents as well as the child.”

And, as previously mentioned, conditions such as ADHD, autism, and other psychiatric disorders are common in people with ARFID. This is another reason why a care team should include a therapist who is experienced with ARFID and a patient's other diagnoses. This way, they can support the patient in every aspect of their mental health, leading to better outcomes.

Registered dietitian

Another important provider is a dietitian who recognizes that there are key differences when treating a patient with ARFID compared to treating someone with another eating disorder. “Equip's dietitians focus on building off of a patient's safe foods list, and collaborate with the rest of the team on coming up with an exposure plan,” Gilchriest says.

This can be extremely helpful to parents of children with ARFID, as well as adults with ARFID. Having a meal plan can ease the anxiety of figuring out what to serve and also eliminates any surprises for the person who has ARFID.

Mentor

Mentors who have recovered from ARFID themselves—or helped a loved one recover—can be vital, Gilchriest says. “ARFID can be an isolating and confusing experience, even within the eating disorder treatment community. Both peer and family mentors offer their lived experience to surround patients and families with the message that they are not alone and that recovery is possible,” she explains.

Other specialties

Depending on the presentation, symptoms, and any comorbidities, some people with ARFID may need to work with other specialists, such as occupational therapists, speech language pathologists, allergists, or gastroenterologists. If it seems that a young patient’s eating difficulties might be more developmentally- or physiologically-based, it’s important to get screened for pediatric feeding disorder (PFD). PFD is a condition that’s similar to but distinct from ARFID and requires a different treatment approach.

The role of exposure in ARFID treatment

As mentioned above, exposure is a core component of ARFID treatment. Exposure and response prevention is a safe, evidence-based approach to exposure that helps patients gradually expand food variety, address food-related fears, and reduce anxiety around food and eating situations.

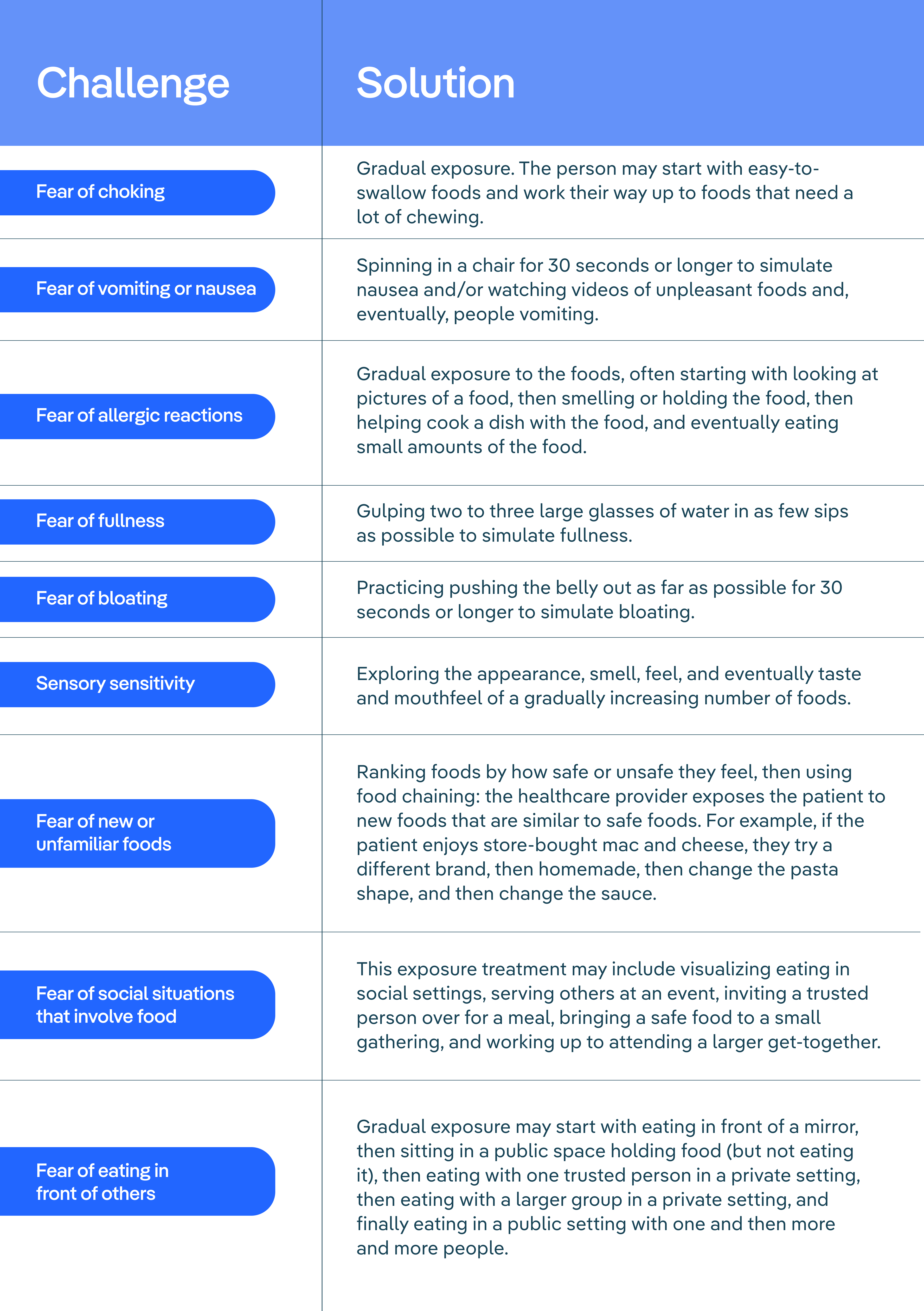

The chart below shares some examples of common ARFID food challenges and possible solutions. Note that the solutions are done in a supportive, safe environment with an experienced provider and are highly individualized. For exposure to be effective, patients must also practice them outside of session by themselves or with a parent, caregiver, or other loved one.

ARFID treatment is available

ARFID is a serious condition—it's not just picky eating or something a child will grow out of—and it needs specialized, professional treatment. The sooner you seek help for yourself or a loved one, the better, because early intervention can make a big difference. Experienced providers understand the nuances of this lesser known eating disorder, and can help people of all ages face down their food anxiety, aversions, sensitivities, or other factors that are contributing to ARFID.

Since ARFID may not be as widely known as other eating disorders, good care may feel elusive. But don't despair, because effective ARFID treatment is out there—and as awareness increases about this unique disorder, we hope that it will become easier to find.

If you or someone you love is struggling with ARFID, you can schedule a consultation to speak with an Equip expert about your treatment options today. Equip is the largest ARFID treatment provider in the United States, and our provider team includes many ARFID clinicians as well as mentors with lived experience recovering from ARFID.

And you’re not sure if you or a loved one might be struggling with ARFID, check out our free, clinically validated ARFID screener.

FAQ

What is ARFID?

ARFID (avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder) is an eating disorder where a person eats a limited amount of food, a limited variety of food, or both. Unlike other eating disorders, someone with ARFID doesn't restrict their eating due to fears of weight gain or concerns about their body. Instead, they struggle to eat because of sensory sensitivities, lack of interest in food or eating, or fear of bad outcomes from eating (such as choking or getting sick).

Can you cure ARFID?

With the proper treatment from professionals who are educated about ARFID, this eating disorder can be cured. Keep in mind, recovery is a process and may take time, but effective, evidence-based interventions make recovery possible for everyone affected by ARFID.

How is ARFID treated?

For patients who need it, the first step of ARFID treatment is to address nutritional deficiencies and help restore weight if a patient needs it. The next goal is to establish a regular eating pattern, which can help with weight gain and restore some natural hunger cues. Then, providers work to increase the amount and variety of food a person will eat. This is often done through exposure exercises in a safe, supportive environment. The patient may also work with a therapist to learn to cope with any uncomfortable feelings or thoughts that arise during situations that involve food. There are several promising treatments for ARFID, including cognitive behavioral therapy for ARFID (CBT-AR), family-based treatment for ARFID (FBT-ARFID), and exposure and response prevention (ERP)

What’s the difference between treatment for ARFID and treatment for other eating disorders?

The main difference between treatment for ARFID and treatment for other eating disorders is the focus on exposure. Although exposure therapy may be used to treat any eating disorder, it's often the core of ARFID treatment. Exposure helps people increase both the variety and amount of foods they eat. Additionally, while treatment for other eating disorders often addresses body image concerns as part of treatment, this is generally not a factor in ARFID treatment.

Is ARFID treatment different for children and adults?

The essence of ARFID treatment is the same for children and adults: through exposure, the patient learns to overcome their struggles with eating and enjoy, or at least accept, more foods. The exact type of treatment through which they receive this exposure may vary, though. Children with ARFID often receive family-based treatment for ARFID (FBT-ARFID). In this modality, parents are empowered to take an active role in their child's recovery. They are responsible for their child's eating and learn to support them as they recover. For adults with ARFID, the recommended treatment is cognitive behavioral therapy for ARFID (CBT-AR).

- Sanchez‐Cerezo, Javier, et al. (2022). What do we know about the epidemiology of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in children and adolescents? A systematic review of the literature. European Eating Disorders Review, 31(2):226–246. doi:10.1002/erv.2964

- Ramirez, Zerimar and Gunturu, Sasidhar. Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder. (Updated 2024 May 1). In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK603710/

- Zimmerman, Jacqueline and Fisher, Martin. (2017). Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID). Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care, 47(4):95-103. doi:10.1016/j.cppeds.2017.02.005

- Seetharaman, Sujatha and Fields, Errol L. (2020). Avoidant and Restrictive Food Intake Disorder. Pediatrics Review, 41(12):613–622. doi:10.1542/pir.2019-0133

- Balasundaram, Palanikumar and Santhanam, Prathipa. Eating Disorders. (Updated 2023 June 26.) In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567717/

- Koomar, Tanner, et al. (2021). Estimating the Prevalence and Genetic Risk Mechanisms of ARFID in a Large Autism Cohort. Frontiers in Psychology, 12:668297. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.668297

- Thomas, Jennifer J, et al. (2018). Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 31(6):425–430. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000454